Secret Wonder Bondage Woman!

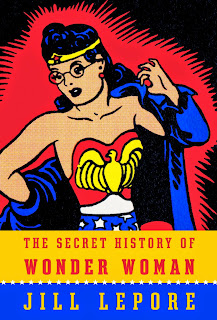

I recently read Jill Lepore's The Secret History of Wonder Woman alongside Noah Berlatsky's Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism, which had the bad luck to be published at nearly the same time. The two books complement each other well: Lepore is a historian and her interest is primarily in the biography of William Moulton Marston, the man who more or less invented Wonder Woman, while Berlatsky's primary interest is in analyzing the content of the various Wonder Woman comics from 1941-1948.

Lepore's book is a fun read, and it does an especially good job of showing the connections between late 19th-/early 20th-century feminism and the creation of Wonder Woman, particularly the influence of the birth control crusader and founder of what became Planned Parenthood, Margaret Sanger. The connection to Sanger, as well as much else that Lepore reports, only became publicly known within the last few decades, as more details of Marston's living arrangements emerged: he lived in a polyamorous relationship with his legal wife, Elizabeth, and with his former student, Sanger's niece Olive Byrne (who after Marston's death in 1948 lived together for the rest of their very long lives). Some of the most fascinating pages of Lepore's book are not about Wonder Woman at all, but about the various political/religious/philosophical movements that informed the lives of Marston and the women he lived with. She also spends a lot of time (too much for me; I skimmed a bit) on Marston's academic work on lie detection and his promotion of the lie detector he invented. As she chronicles his various struggles to find financial success and some sort of renown, Lepore's Marston seems both sympathetic and exasperating, a bit of a genius and a bit of a con man.

Because she had unprecedented access to the family archives, and is an apparently tenacious researcher in every other archive she could get access to, Lepore is able to provide a complex view not only of Marston and his era, but especially of the women in his life — the women who were quite literally the co-creators of Wonder Woman: Marjorie Wilkes Huntley, Elizabeth Marston, and Olive Byrne. She is especially careful to document the contributions of Joye Hummel, a 19-year-old student in one of Marston's psychology classes who, after Oliver Byrne graded her exam (which "proved so good she thought Marston could have written it") was brought in to help work on Wonder Woman. Originally, Marston thought he could use Hummel as a source of current slang, and to do some basic work around the very busy office. "At first," Lepore writes, "Hummel typed Marston's scripts. Soon, she was writing scripts of her own. This required some studying. To help Hummel understand the idea behind Wonder Woman, Olive Byrne gave her a present: a copy of Margaret Sanger's 1920 book, Woman and the New Race. She said it was all she'd need." When Marston became ill first with polio and then cancer, Hummel became the primary writer for many of the Wonder Woman stories. (Lepore provides a useful index of all the Marston-era Wonder Woman stories and who worked on them, as best can be determined now.)

|

| Lou Rogers, 1912 |

|

| H.G. Peter, 1943/44 |

Marston was hardly a perfect man or role model, and one of the things the story of his life and the lives of the women around him shows is the complexity of trying to live outside social norms. While Marston had some extremely progressive ideas not only for his own time but for ours as well, he was also very much a product of his era and location. That's no earth-shaking insight, but Lepore does a good job of reminding us that for all his liberalism and even libertinism, Marston still had many of the flaws of any man of his age, or of ours. He truly seemed to dislike masculinity, and yet lived at a time when it was difficult to imagine any way of living outside of it or its hierarchies, and his ways of analyzing the effect of masculinity and patriarchy were very much bound by his era's common notions of gender, biology, propriety, and race. Lepore does a fine job of showing not only how the assumptions and discourses of a particular time, place, and class situation shape notions of the possible in Marston's life, but also in the lives and politics of the early 20th century feminist movement.

However, Lepore's book is seriously under-theorized, and that's where Berlatsky comes in. The Secret History of Wonder Woman is aimed at a general audience, and Lepore is a historian, not a theorist. This would be less of a problem if Marston's life and work didn't scream out for the insights of someone familiar both with feminist theory and, especially, queer theory. (Lepore actually seems quite uncomfortable with the sexual elements of the story, and even more so in an interview she did for NPR's Fresh Air, where she can't help giggling over it all.) Berlatsky makes the excellent choice to take the queer elements seriously. He organizes his book into three large chapters, the first focusing on feminism and bondage, the second on pacifism and violence, the third on queerness. A brief introduction gives background on the comic and its creators; the conclusion looks at Wonder Woman's (sad) fate after Marston's death.

Berlatsky's writing is accessible — he's perhaps best known for founding the Hooded Utilitarian blog, so he's used to writing for a non-academic audience. (The blog has tons of Wonder Woman material, including lots from before the book, so you can follow Berlatsky's thinking as it develops, get more information and imagery, and see Berlatsky in conversation with many thoughtful, informed commenters and guest bloggers.) Though his prose is not heavily academic, Berlatsky is well-versed in comics scholarship and has some good knowledge of both feminist and queer theory, all of which he uses to fill a relatively short book with a real density of ideas. It helps that the early Wonder Woman comics are so strange and suggestive; even after Berlatsky's most thorough analyses, it still feels like there's plenty left to say. (Which is no slight to him.)

In the introduction, Berlatsky describes the 1941-1948 Wonder Woman comics as “…an endless ecstatic fever dream of dominance, submission, enslavement, and release.” His first chapter then offers various ideas about bondage and fantasy, with the majority of its pages devoted to a complex reading of Wonder Woman #16 (you can see Berlatsky first thinking about this issue in a 2009 post at HU that gives a good overview the plot and substance, as well as lots of samples of the art). Ultimately, Berlatsky argues that the story is a representation of, among other things, incest ... and I'm not sure I followed him there. Something about the analysis feels forced to me, though I don't have any good rebuttal to it.

Chapter Two was more convincing for me, as Berlatsky has some cogent insights about violence, maleness, and superheroes: "Looking at Spider-Man's origin makes clear, I think, that superhero violence is built on, and reliant on, masculinity." Is Wonder Woman different? "It is certainly true that, in Marston and Peter's initial conception, Wonder Woman, like other heroes, often solves problems in the quintessentially superhero manner. That is, she hits things." Wonder Woman also participated in World War II, as the first appearance of her character coincided with the US entry into the war. "It was natural that Wonder Woman's alter-ego, Diana Prince, worked as a secretary for army intelligence, just as it was natural for Wonder Woman herself to foil spy rings and Nazi plots. Superheroes and war went together as surely as did goodness and power." But Marston wanted Wonder Woman to be something other than just a fist-fighting warrior, thrilled to hit anybody she could find. She is a fighter, but, Berlatsky says, a pragmatic fighter for peace: "The Nazis embody war; therefore, fighting the Nazis is fighting on behalf of peace. Or, more broadly, masculinity embodies war; therefore, fighting on behalf of an America that Marston sees as feminine means fighting on behalf of peace."

Berlatsky then goes on to show how some of Marston's psychological and social theories (particularly about the force of love) find expression through the Wonder Woman stories. Coming off of Chapter One, I was a bit skeptical about all this, but by the end of Chapter Two, I'd pretty well been convinced. The evidence Berlatsky marshalls from Marston's writings, particularly his book Emotions of Normal People, is compelling. (Emotions of Normal People itself is a fascinating source. Lepore describes it thus: "Emotions of Normal People is, among other things, a defense of homosexuality, transvestitism, fetishism, and sadomasochism. Its chief argument is that much in emotional life that is generally regarded as abnormal…and is therefore commonly hidden and kept secret is actually not only normal but neuronal: it inheres within the very structure of the nervous system." Berlatsky uses it well in the second and third chapters to show where some of the oddest Wonder Woman moments derive from.)

Chapter Three is what really won me over, I will admit, particularly because Berlatsky brings in ideas from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Julia Serano to explore the implications of various situations and images throughout Wonder Woman. As it explores Marston's lesbophilia and the manifold queer implications of the Marston-era Wonder Woman comics, the chapter ranges across all sorts of subject matter, including, among other things, James Bond and Pussy Galore (from Goldfinger). Berlatsky notes that unlike Ian Fleming's women "Marston's women don't want the penis; rather, his men want the absence of a penis — a unique female power."

There's too much good stuff in this chapter for me to summarize, but one especially interesting bit involves the relationship of the vagina and penis in Marston's idea of sex. Berlatsky quotes Emotions of Normal People: "The [woman’s] captivation stimulus actually evokes changes in the male’s body designed to enable the woman’s body to capture it physically. …[During sex] the woman’s body by means of appropriate movements and vaginal contractions, continues to captivate the male body, which has altered its form precisely for that purpose." Berlatsky summarizes: "Penises don't defile Marston's vaginas; on the contrary, Marston's vaginas swallow up penises."

(If that sentence doesn't make you want to read this book, then there's really no hope for you!)

Berlatsky then shows how these ideas play out in Wonder Woman. "Men in Wonder Woman are never as disempowered and objectified as women in James Bond or gangsta rap or Gauguin — a couple thousand years of tropes don't just vanish because you have a vision of active vaginas. Thus, when Marston flips the binary from masculine/feminine to feminine/masculine, the result is not simple hierarchy inverted. Rather, it's heterosexuality inverted — which is another way of saying it's queer." He then develops this idea to show that "For Marston, essentialism and queerness are not in conflict. Instead, queerness is anchored in, and made possible by, an essentialist vision of femininity. Femininity for Marston doesn't just appear to be strong and love; it is strong and loving. Women for him capture men not just as metaphor but as scientific fact. And it is from those beliefs that you get [in Wonder Woman #41] Sleeping Beauty rescued/captured by a semisentient vagina, or men turning into women on Paradise Island. Femininity makes the world safe for polyamory. You can't have the second without the first."

It's these sorts of insights that would have brought more nuance and complexity to Lepore's portrayal of the role of early 20th-century feminism in Marston's creation of Wonder Woman, but we can be grateful that we can read the two books together.

I've only barely touched on Berlatsky's arguments here, and may have misrepresented them simply by trying to summarize, so if they seem especially bizarre or off-base, check the book. (They may still be bizarre, but to my thinking, at least, they're more often convincing than not.) It's an extremely difficult book to summarize because its ideas and arguments are carefully woven together, even as, in an initial reading, it all often feels quite off-the-cuff, like an improvised high-wire act.

Wonder Woman has suffered in popularity in comparison to male superheroes, and even in this age of wall-to-wall superhero media, a planned Wonder Woman movie has had all sorts of problems getting started. Of course, no Wonder Woman is going to be Marston's Wonder Woman, which is one reason why it's unfortunate that DC hasn't been able to finish re-releasing the 1941-1948 Wonder Woman stories — some, as far as I can tell, have never been reprinted at all, and the most comprehensive collection, part of the DC Archive Editions, petered out after seven volumes, ending with issues from 1946. (Wonder Woman: The Complete Newspaper Comics is quite good.) For the casual reader, the material in the Wonder Woman Chronicles, which got up to three volumes before apparently stopping in 2012, works well, though some of the best and craziest comics come later. There just doesn't seem to be enough demand from readers, and so a trove of wondrously strange material remains generally unavailable.

Perhaps Lepore and Berlatsky's books will create enough new interest to spur DC at least to finish the Archive Edition releases. Personally, what I'd most like to see is a 300-400 page "Best of the Marston Years" collection edited by Berlatsky, because only the real die-hards need all of the various Wonder Woman stories, and it would be nice to have a one-volume edition of the most engaging and exemplary material.