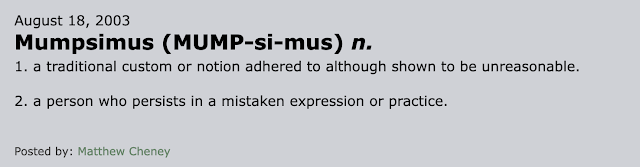

20 Years of The Mumpsimus

On August 18, 2003, I clicked "publish" on the first post of The Mumpsimus blog. That very first post was a simple definition of the word of the title. The next day, I wrote a statement of purpose . And then kept going. (Thanks to the Web Archive, you can see what the original version of the The Mumpsimus looked like.) All together, it's 2,074 posts and who knows how many millions of words. In 2013, I wrote a series of posts looking back year by year at the blog's first decade. That's as thorough a chronicle of the origins as I can make, and since it was ten years closer to 2003 than we are now, it's probably more reliable than my ever-less-reliable memory. Looking back at those lookings back, I'm pleased that in the post about 2003 , I highlighted my friendship with Ann and Jeff VanderMeer. Jeff and Ann were up here for Readercon last month (Jeff was Guest of Honor) and we hung out together with Eric Schaller for a few days in Boston afterward. (It...