Revisitation: Men on Men: Best New Gay Fiction (1986)

Background

I have begun a project to read all eight volumes of the Men on Men series of anthologies published between 1986 and 2000. (I hope also to read various other such anthologies — for instance, there were three [I think?] Women on Women anthologies from 1990-1996, the His: Brilliant New Fiction by Gay Writers and Hers: Brilliant New Fiction by Lesbian Writers series, etc. — but I am not a fast reader, so need to take this one step at a time.)

I am interested in looking at queer short fiction in the last two decades of the 20th century, for a variety of reasons. The first reason is recuperative: a lot has been forgotten because of changes in the publishing industry, changes in society, the inevitable effects of time, and the fact that a significant proportion of these writers died early in their careers because of AIDS. That links to another reason for this reading: curiosity about how much of this material holds up, either as historical artifact or aesthetic achievement (or both). There are also personal reasons. This was the era I came of age, the era when I recognized some of the fault lines of my own sexuality, the era when I most deeply explored my sense of identity, the era when I moved from rural New Hampshire to Manhattan for college. (See my LitHub essay about this time for more on all that.) I remember seeing the later volumes of the Men on Men series on bookstore shelves, Men on Men 5 most vividly, because that was the new one when I first arrived in New York. I didn't buy any of the anthologies then because I wasn't reading a lot of fiction (with very limited money, most of the books I bought were nonfiction and plays), but they were there, visible in store windows and on front tables when they were published. I read, haphazardly, the gay press, and I spent time at A Different Light and the Oscar Wilde Bookshop, so I knew writers' names, knew the hot new books, noticed obituaries.

With the naivety of youth, I thought queer short fiction would always be there. Rarely do we know when we're living in a golden age. (Most golden ages don't, after all, feel very golden.) I should be more precise, though. The golden age was not so much of queer short fiction generally as it was for gay male short fiction specifically — note that the Men on Men series sold very well for a while and made it through eight volumes from a major publisher; Women on Women was less popular and didn't last as long. There were numerous one-shot anthologies of gay male fiction that garnered attention and sold relatively well; anthologies of lesbian fiction were fewer and farther between (though often excellent — see the essential Chloe Plus Olivia, a book that in its size and scope screamed out from the shelves, "Hey, numbnuts, we're here, too!"). Short fiction from other even more marginalized groups was either just beginning to be seen and appreciated or, most often, those groups and their writing were completely illegible not only to the general reading public but to the mainstream gay and lesbian organizations and publishers. The reasons for all this are far more complex than I can fit in this paragraph, and I'm sure I'm not even aware of some of them, but I'm certain that patriarchy and misogyny had something to do with it because patriarchy and misogyny shaped a lot of the literary (and social) landscape at that time — and of course do today, but there has been significant progress as well.

There are today plenty of queer writers of short fiction, and the landscape is more diverse in just about every way you might measure diversity (except, perhaps, aesthetically, but that's a conversation for another time — see my post "Artificial Jungles"). Gay male short fiction was, during the time of the Men on Men series, a category, almost a genre. Lesbian writing might (depending on the era and ideology) have a home within the larger tent of feminist writing generally, but gay male writing was its own thing. Categories, however niche they may be, exist when there is an ecology for them to exist in, an infrastructure of writing, publishing, distribution, and reading. Often, as in this case, the categories exist because more mainstream systems of publishing and distribution do not connect a certain type of writer and writing with an audience seeking it. If in the 1980s and early 1990s your gay male writing respected mainstream values and expectations, you might be lucky enough to publish with a major venue — David Leavitt in The New Yorker, for instance — but those spots were extremely rare and mostly tokenistic, whether by design or effect. (Edmund White, one of the most prominent gay male writers of the time, didn't land a story in The New Yorker until 1995. The straight public was not interested in reading one gay male story after another. Thus, publications like Christopher Street and The James White Review became vital for both a certain group of writers and a certain group of readers.

Eventually, everything changed. HIV became for many people a manageable, chronic disease; Amazon and the internet blew up the publishing world; U.S. culture became generally more accepting of some kinds of homosexuality and bisexuality, particularly the kinds that flattered capitalism and families; transgender and genderqueer people finally gained some little bits of real visibility in the culture (though there's still a long long way to go toward equality, and there's a fierce backlash); young people embraced ideas of gender fluidity that shocked even some of their more radical elders; most gay bookstores closed; many gay bars closed; "the community" revealed itself to be, in fact, many communities.

With all these changes, short fiction seemed to become less important to queer culture. It had never been as important as other forms, but in particular for writers and readers in precarious health, short stories were more manageable than novels. In an interview in Gay Fiction Speaks, Andrew Holleran says, "Edmund White said something perceptive about AIDS writing early on: he thought the way to deal with it was possibly with the short story, because you were in and out quickly and didn't have to have an ending the conventional way. He was right." In the age of the internet and social media, attention spans were supposed to be shrinking. This would seem to be fertile ground for short stories. But fewer and fewer people, gay or straight, now seem to read short fiction unless it gets assigned to them in school. (Short stories are ideal for classrooms.)

As a reader and writer of short stories, I wish it was a more popular form. But I can't really complain too much about the social changes, because I would much rather live now than go back to living twenty years ago. I enjoy the efflorescence of queerness across the land, and personally feel much more comfortable in our more open world, both more open generally and more open than it was back in the days of "the gay community", a community I never felt much of a part of myself.

But in all changes, things get lost. I am reading through the Men on Men anthologies to see what might be worth revisiting, preserving, and even, perhaps reviving.

Contents

(source in parentheses if previously published elsewhere)

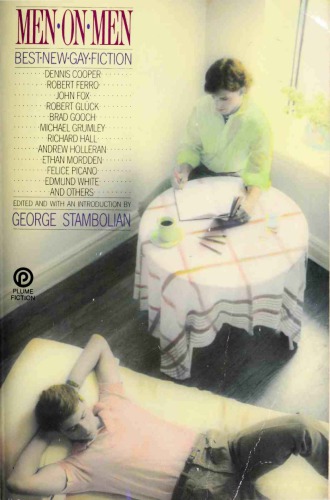

Men on Men: Best New Gay Fiction edited by George Stambolian, Plume/NAL/Penguin, 1986, 375 pages.

This first volume of the series includes both reprint and original stories, with none of the reprints being older than 1982. Though the copyright page lists the first printing as November 1986, my (paperback) copy is a later printing and includes biographical notes that seem to have been silently updated to 1988.

Speech by Richard Umans (The James White Review)

Choice by John Fox

A Queer Red Spirit by C.F. Borgman

Maine by Brad Gooch (Jailbait and Other Stories)

Friends at Evening by Andrew Holleran

Bad Pictures by Patrick Hoctel (Mirage)

Nothing Ever Just Disappears by Sam D'Allesandro (No Apologies)

David's Charm by Bruce Boone

The Most Golden Bulgari by Felice Picano

Backwards by Richard Hall (Letter from a Great-Uncle and Other Stories)

Hardhats by Ethan Mordden (Christopher Street)

Street Star by Wallace Parr

Life Drawing by Michael Grumley

Sex Story by Robert Glück (Elements of a Coffee Service)

Second Son by Robert Ferro

The Outsiders by Dennis Cooper

September by Kevin Killian

An Oracle by Edmund White (Christopher Street)

The reprints are the stories by D'Allesandro, Glück, Gooch, Hall, Hoctel, Mordden, Umans, and White. A few of the pieces are novel excerpts rather than stories: "David's Charm" is from Boone's unpublished/abandoned novel Carmen (other pieces can be read in Bruce Boone Dismembered), Picano's piece is from his memoir Men Who Loved Me, Grumley's is an excerpt from his novel Life Drawing, Ferro's from his novel Second Son, Cooper's from his Closer, and Killian's became part of the end of his first novel, Shy. 12 of the 18 stories are first-person point of view.

Notes

Overall, this is not an especially memorable collection; there aren't many real clunkers, but there are only three or four standouts, and the high quotient of novel excerpts is a real weakness. Many of the stories present familiar sorts of angst: outsiders who are not understood by their families, young people who end up as tragic wastes, men who live in NYC or San Francisco and have a lot of sex and worry about dying or getting herpes or losing their looks. Of John Fox's "Choice", I wrote in my notes: "Every character is miserable and awful, but none are interesting." That's true of more than just this story. (The most interesting detail in Fox's story is that the protagonist hopes to someday save enough money to buy a VCR so he can watch porn at home rather than having to go to the theatres. A telling moment of history!)

C.F. Borgman's "A Queer Red Spirit" is billed as the author's first-published story. It's a somewhat clunky supernatural fantasy that is good enough to be annoying that it's not better. Borgman went on to publish a novel, River Road, that sounds quite interesting from Amazon reviews (the only notices I've found of it), but I haven't been able to find any more information about him.

Holleran's "Friends at Evening" is the first really solid story in the book, a slice-of-life tale of three friends preparing to go to a funeral for another friend who died of AIDS. The story is mostly told in dialogue, and some of the characters would become part of Holleran's 1996 novel The Beauty of Men, though I haven't checked to see if the story itself is reworked into the novel. Many features of this story's setting and situation would become familiar with later writing about the era and AIDS, almost to the point of cliché, but Holleran is such an astute writer that "Friends at Evening" works well both as a short story and, for us now, as a window into a lost world. Reading Men on Men in order, I got to this story and thought, "Okay, no more amateur hour." Unfortunately, there are only a few stories of similar depth through the book.

Richard Hall's "Backwards" is a well-written story with a time-in-reverse conceit that almost works. A bit like Pinter's Betrayal, it tells the story of a relationship from end to beginning, but via an old-to-young movement as in "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button". It's a bit confusing, and there's some handwaving regarding what's going on and how it all works (this is more surrealism than science fiction), but the writing is smooth and detailed, and what at first I thought was going to be quite a clunker ended up being both strange and moving.

Ethan Mordden's "Hardhats" is one of his popular "Buddies" stories, important for capturing the everyday life of certain types of gay men in 1980s New York. It's simplistic, even naive and sentimental in its wonder at the working class man who just wants a buddy, as long as that buddy is strong and not weak. But there's a certain charm to it.

"Street Star" by Wallace Parr is a tragic melodrama with a commitment to relentless gloom that verges on camp. The story concerns a young trans woman who finds her way to NYC, hangs out at Warhol's Factory, gets in trouble, lives in cheap hotels, never finds the love or stardom she seeks, and dies unnoticed in her room, her body eaten by cats and cockroaches. There's an overblown absurdity at the end that is weirdly hilarious yet also somehow affecting. The story is told in long, languorous paragraphs, giving the whole an ethereal effect. The bio note in the book says that Parr was a member of Robert Glück's famed writing workshop in San Francisco, but I haven't been able to locate any more information about him.

Speaking of Glück, "Sex Story" is the oldest (1982) and one of the best stories in Men on Men. It's a sly story, one that until its last pages seems to be exactly what its title says: a chronicle of sex. The majority of the story offers a kind of memoir of the days when gay sex was easier and less terrifying. But Glück gives it a powerful turn at the end, which turns on a letter from one of the narrator's lovers, a letter that seems separate from the concerns of the story because it's about the lover's childhood, his mother, and especially his grandmother's death. What was a sex story ends with distance, memory, death — and published just as AIDS is bringing death to a whole community, rendering the world the story describes into nearly inaccessible history. The genius here, though, is that the slyness of the narrative prevents the story from feeling smothering. It's not nearly as depressing as other stories in the book, even though it is as deeply concerned with serious topics. It's one of the three really strong stories in Men on Men, with the others being by Holleran and White. Recently, it was reprinted by Dale Peck in The Soho Press Book of 80s Short Fiction (a good anthology, well worth checking out if you haven't).

Kevin Killian's "September" is weird, confusing, and inconclusive — even though it's not labeled as an excerpt in Men on Men (as other excerpts are), I was sure when I read it that it must be part of something else, because it just feels too much like something plucked almost at random out of a larger text. The story stands out for its weirdness and its complicated point of view. The inconclusiveness was what most bothered me about it, because it felt on the verge of some sort of greatness. Researching it, I discovered it's part of the 1989 novel Shy, and though I don't know if Killian had at that point incorporated it into the novel, it's a book he had been working on for a long time, so I'm sure he at least thought of "September" as adjacent to it. It's the story of a 13- or 14-year-old boy who is kept by an older man, apparently not against his will, but there are references to restraints and abuse. The story is so deep in the boy's perception, though, that it's hard to tell what is and isn't happening, especially as he is clearly disturbed and hardly reliable. Of Shy, Lonely Christopher wrote in Evergreen Review:

[Killian] isn’t nostalgic for youth; he’s kind of horrified by it. This is still a world where if a boy makes the wrong mistakes he gets knifed to death, like Kevin’s murdered friend who he is trying to memorialize in prose: a raunchy dumbass who went home with the wrong guy one night. After much obsession, Paula finally bags Gunter but immediately starts to irk him so he moodily dumps her. Harry desperately wants to be kidnapped by Gunter, who finally caves in and does it, perhaps more out of frustration than lust. Kevin, the author living upstairs, lies down on the floor and listens in on their tortured dealings with his ear to a water glass. He wants in on the action as well. Of cute little fifteen- or sixteen-year-old Harry, Kevin drools, “I wanted him to eat my candy and peanuts till the end of Time.” When Gunter inevitably rejects the kid in a fit of self-loathing, Harry runs upstairs into Kevin’s arms and hides out in his bedroom. Not that it engenders much conflict. Instead of bubbling toward an inevitable climax, the culmination of this story is abrupt and bathetic. It left me pristinely unsettled, realizing that of course the conclusion would be as grumpy and ambivalent as the characters themselves.Finally, the second-longest story in the book (a couple pages shorter than Picano's memoir excerpt), "An Oracle" by Edmund White, originally published in Christopher Street, reprinted in both A Darker Proof (his joint story collection with Adam Mars-Jones) and Skinned Alive. It's a slow, affecting story of a 40-year-old man whose lover has recently died of AIDS, who heads to Greece to figure out his life and ends up falling in love with a young Greek man he first picked up for sex. The young man is fond of him but also sends him on his way, displaying a bit more maturity and understanding of the world (and himself) than the older man. It's a slow burn story, one of those that ten or even twenty pages in you're not sure what it's up to, but by the end it turns out it's all been carefully put together, the payoff significant both emotionally and intellectually. This and "Sex Story" are the only two stories in the book I had read before, and I am fond of them both, though this one has a particular place in my heart because Skinned Alive has long been among my favorite of Edmund White's books, and this story is just a beautiful presentation of grief and age in a certain type of gay man who was prepared for neither. I've been a bit hesitant about the final sentence since I first read it, because it feels heavy-handed to me, tying itself back to the title in an obvious way — but I also can't deny that it always makes me catch my breath, and that matters more than a slight obviousness.