What's Queer About Autofiction? (Part 3)

|

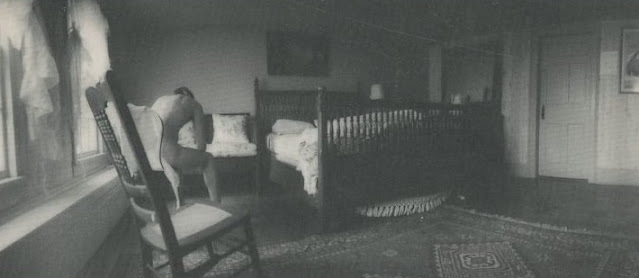

| October 1990, New York City, photo by Tracey Litt |

This is the concluding installment of my conversation with Richard Scott Larson about fiction, nonfiction, autofiction, queerness, memory, community... Part 1 is available here, Part 2 here.

Though this is the last installment, we deliberately kept away from any sort of concluding summary or anything like that — indeed, I'm not sure Richard meant his PS to be the final words here, it might have just been meant for me, but I thought it was absolutely the perfect spot to bring all this to a close.

|

| David Wojnarowicz |

Dear R—

Reading through your most recent letter helped me identify what’s been lurking in my subconscious without my awareness, a question I hadn’t thought to ask — why do I (and you?) hunger for explicitly, determinedly queer writing now?

I thought about this while reading a short piece by Sam Moore at Frieze about Daniel Levy’s Met Gala appropriation of David Wojnarowicz. I like Levy’s public persona, but he’s a liberal gay entertainer, and I like Wojnarowicz — a radical queer artist — a lot more, so I was aghast when I saw Levy’s costume. “It wasn’t so much that it repurposed Wojnarowicz’s work,” Moore writes, “but more that as an act of adaptation it both maimed and fundamentally misunderstood it – turning references to the experience of living with AIDS, and the legacy of a major figure in the history of AIDS activism/art, into a fashion accessory. … Levy's Wojnarowicz look extracted only the parts that most easily fit with mainstream narratives of LGBT+ acceptance.”

That is why we need queer writing now. Because otherwise all we have are those mainstream narratives, those commodifications of art, those good and shallow feelings wrapped around rainbow-colored gallows.

Last week, I returned to Michael Hobbes’s extraordinary 2017 article “Together Alone: The Epidemic of Gay Loneliness” because a friend is going through a horrible time at his workplace and we were chatting about how dealing with certain kinds of anxiety and trauma is made much more difficult by the survival practices we develop as kids and young adults and even adults because of queerness. There’s the general stress of any minority group, but there’s also the specific experience of a minority identity that you first come to awareness of alone. This conversation I had with my friend reminded me of Hobbes’s article, so I sent it to him, and he said he’d seen it floating around social media when it first came out but this was the first time he’d really sat with it, and ohhhh.

And then I read Anne Helen Peterson’s new article at Vox, “The Escalating Costs of Being Single in America”, which isn’t about queerness specifically, but in passing includes a statistic that is in line with statistics in Hobbes’s article: “According to Pew’s most recent survey data … 47 percent of adults who identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual are single, compared to 29 percent of straight adults.” It’s not that I want to point to single as a terrible thing (I am quite happy with the status, myself), but rather the stark difference, statistically, between the two groups.

All of which is not to say oh poor us! but rather to point toward the obvious: queer life is different. It’s not a monolith, by any means, because the differences of class, gender, race, ability, etc. that inflect any group are just as present with us, but there is a uniting, common, base-level experience to lgbtqia+ life that deserves to be acknowledged, chronicled, narrated. As much as I may not want to admit my commonalities with a milquetoast, mainstream, normativity-loving gay guy like Pete Buttigieg (the personification of whatever is the homosexual opposite of queer), I bet if we got into a conversation, we would find areas of common experience significantly different from those of our straight friends and colleagues.

And there lies the importance of an idea of community. Hobbes’s article is clear about the dangers of the queer community, particularly for men (since masculinity is so toxic), but my own experience of that community, especially when younger, was mostly positive and, indeed, made living worthwhile.

Especially in a time of great aloneness, literature may be a tool of community. That’s the lesson of the New Narrative for me. I wonder how and where we might find community again, how we might use writing to extend community, to render the inevitable aloneness more bearable. I wonder, too, how we might mitigate the failures, dangers, and disappointments of community — I’ve felt this recently when I had a story rejected by a specifically queer market and then a book manuscript rejected by a primarily queer market. I’m unlikely to submit work to such places again, at least anytime soon, because unlike all the other rejections I routinely get, those felt different — those were rejections from the community I feel most connection to, the one community I actually do want to be good enough for. That gets me thinking about what community might look and feel like for me, a middle-aged queer living in rural northern New England, a kind of identity and location that requires a different sense of community than other identities and locations might, a kind of community I really don’t know how to find or grow — and maybe don’t really need, but just feel wistful for.

I remember when I was young how empowering the motto of Queer Nation was: We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it! — first because of that bold and assertive final clause, but then later, after I’d lived with it for a while, even more because of the first two clauses. Hence the pleasure and attraction of queer nonfiction, memoir, autofiction for me. Perhaps this is too reductive and general a statement, but I will make it anyway, casting caution to the winds: valuable queer autofiction always starts from the premise: We’re here, we’re queer.

You mention Erik Hoel’s piece about MFAs, which I haven’t read. I saw stuff on Twitter about MFAs and all, but I avoided it. (The only commentary I read on MFAs these days is about the way schools tend to use master’s programs as machines of profit creating massive debt for unwary students.) What you quoted gets at something important even if the quote is quite flagrantly wrong about at least the kind of autofiction I find interesting. I do think writers ought to be writing about people other than themselves, ought to be striving for everything they possibly can beyond the self, ought to be failing at that flagrantly and still trying, because that’s what I like in art. But it has to be the result of effort, not faddishness. (Some of my favorite queer works were created by straight people — the movie Happy Together, for instance.) The good stuff from straight people works for me because these folks put in the effort to stretch their sensibilities beyond their own feelings, thus producing something that creates what is, for me at least, work of powerful resonance. And I definitely think fear of being perceived as wrong — fear of online mobs wielding identity as a weapon, declaring their own experience of identity to be the One Truth that must be abided — inscribes itself into some contemporary American narratives, leading to earnest, unobjectionable writing that is inevitably familiar and predictable. If Hoel is complaining about how unsurprising, how choir-preaching, how narrow in its aspirations a lot of contemporary “serious” writing is, then I’m with him even if I would disagree about the particulars. I expect I would also disagree about the causes, actually. My own take is that our problem is we think we’re good people, and write as if to confirm our goodness, when in fact there is really no way to be a truly good person if you are an American who participates in our consumer economy and/or pays taxes. (Another favorite autofiction, though not queer: Wallace Shawn’s The Fever.)

I am somewhat (somewhat?!) anomalous in my feeling that we ought to write from a sense of our own awfulness and complicity with awfulness. I suppose that’s why I liked Jarrett Kobeck’s wonderful failure of a novel Only Americans Burn in Hell (autofiction of a sort). From that book:

This was the truth that the political liberals could not deny and could not face: beyond making English Comp courses at community colleges very annoying, forty years of rhetorical progress had achieved little, and it turned out that feeling good about gay marriage did not alleviate the taint of being warmongers whose taxes had killed more Muslims than the Black Death.

You can't make evil disappear by being a reasonably nice person who mouths platitudes at dinner parties. Social media confessions do not alleviate suffering. You can't talk the world into being a decent place while sacrificing nothing.

There is, though, a problem that easily gets elided if we only talk about identity, imagination, freedom, and sacrifice — the problem of power. (Bessie Head, A Question of Power: “Love is two people mutually feeding each other, not one living on the soul of the other, like a ghoul.”) Who gets to experiment? Who gets to write beyond themselves? Who gets noticed, who gets praised? Within the writing itself, it’s a problem Rebecca Solnit has called the “misdistribution of sympathy”. Where does sympathy go? Whose perspective is highlighted? Whose consciousness gets to live in the reader’s? I’ve sort of raised these questions about autofiction in the past, questions of what gets called autofiction and what that label does in different contexts.

I have no interest in giving cookies to straight white cis guys, but I am honestly glad when they try to expand beyond their own consciousness, and I want them to feel encouraged to do so (with humility!), even if I may not be rushing out to read it. (I wrote more about this at tedious length a few years ago in a post called “What Is to Be Done about the Social Novel?”) I want straight white cis guys to revel in imaginative freedom, and to expand what they can imagine, but even more so I want people who aren’t exactly (or even remotely!) straight white cis guys to feel that freedom. I want us all to think about where and how we direct attention, sympathy, judgment, respect. And some of us probably need to step out of the way for a while so we don’t continue to suck up all the air in the room.

I also want to hold on to some of our outsider standing, our danger to the status quo, our bad reputation. Think of it as our (Kathy) Ackerness. Keep queer weird. I don’t just want queer autofiction, I want to queer autofiction. And everything else of any value. (Not warmongering. I do not want queer war machines, but rather for queerness to be a wrench thrown into the war machines.) That’s the only way to resist commodification and assimilation in our neoliberal reality. I want us queers to be the demons possessing the mainstream imaginary. I want us to seize the means of dream production.

Thanks to you — without whom I probably wouldn’t have given the term autofiction much thought at all — I’ve been thinking about autofiction as the fiction of self and the self of fiction. Autofiction as a queer epistemological tool that highlights the self not, ideally, for the purpose of ego but for the purpose of expanding ego into a community. (Which may simply be a community of language.) The fiction part is key because that’s what problematizes self. That’s what allows the transcendence of self. I’m applying my own biases here, because for me a (the?) fundamental problem of existence is how to reconcile the inevitably solipsistic experience of consciousness with the vast world outside — and beyond — that solipsistic experience. My ideal for autofiction would be for it to use fiction to dispel, counteract, and perhaps even heal the deepest, most destructive forces of the self.

Did you ever read Dale Peck’s Martin and John? (Have I asked that before?) I think I read it my freshman year of college (maybe a year earlier). Before I found it, I’d read Paul Monette’s memoirs and really loved them, read Edmund White’s autobiographical novels and sort of liked them, but it was Martin and John that really sliced the top of my head off and made me excited for a particularly queer narrative. The situations for the characters are different and contradictory chapter by chapter, but a core remains, a through-line, and the cumulative effect is overwhelming. The book could almost be called the dispersal of self. Or maybe what persists. Is it autofiction? I don’t know. I just know I want more of that.

“Is this fiction?” someone asks the Zen master of autofiction.

The Zen master of autofiction slams a hand to the floor and shouts: “YES!”

“Is this nonfiction?”

“YES!”

“Is this autobiography?”

“YES!”

“Is this completely imaginary?”

“YES!”

“Is everything true?”

“YES!”

Yes?

—M

|

| photo by Melanie Acevedo from the cover of Martin & John |

Dear M—

You wrote something at the beginning of your last letter when sharing the anecdote about your friend’s recent struggles that I think gets directly at something I’ve been trying to articulate in many different forms: “There’s the general stress of any minority group, but there’s also the specific experience of a minority identity that you first come to awareness of alone.”

I wrote about my current deep interest in AIDS narratives and accounts by writers like Guibert and Wojnarowicz back in my first letter, and I think this element of aloneness (and the rage that builds up because of it) is what I think is particularly “queer” about the experience of diagnosis: the idea that the AIDS victim discovers this new identity alone and then has to choose how (or if) to live with it—to come out, as it were, again; to be doubly afflicted by an identity that isn’t visible to the world. Isn’t that the appeal of narratives about racial passing—the stakes of a character being something other than what they seem, and then the inevitable crisis of discovery? I think this crisis of discovery is something I’m endlessly interested in exploring.

My own memoir manuscript is ultimately about the experience of a closeted childhood and its lingering effects into and throughout adulthood, and I think that burden of being the first to know and the shame that it causes, at least initially, is how a lot of the queerness I identify with is formed: sitting with it for years, experimenting with it in fits and starts, holding it in our hands alone for as long as it takes and trying to figure out what it means. And, of course, hopefully getting to the point where we can say, “I’m here, I’m queer, get used to it,” which you write is the premise that valuable queer autofiction should start from (and I agree). I’ve been thinking about memory and nostalgia when it comes to this genre we’re calling queer autofiction and how so much of it seems to be about the past—our own personal histories, of course, but also the general queer past, eras of queerness that no longer exist (for better or worse).

I recently devoured the fantastically brilliant and deceptively spare My Dead Book by Nate Lippens, which begins as a chronicle of individual people in the narrator’s life who have passed away over the years, including various friends and lovers. But then the novel becomes a (slightly) more straightforward narrative orbiting around ideas of generational and personal memory, conversations that the narrator has with various other friends and acquaintances revealing a deep and deeply moving longing for a world that no longer exists. I’m thinking here about the quote you shared about Dan Levy’s appropriation of Wojnarowicz in wearing that outfit to the Met Gala and how the mainstreaming of queer history always errs on the side of blurring out the darker contexts in exchange for something more palatable for a general audience. More “positive,” let’s say. And maybe the queer autofictional impulse is to haul all that painful context back into the light.

My Dead Book made me think a lot about what role nostalgia plays in autofiction, specifically queer autofiction, especially when related to bygone periods of queer history. There’s a scene in which the narrator’s friend Rudy is recalling what it was like being gay in the 1980s (“So much cock. All kinds. Cock, day and night. Cock around the clock.”) and the narrator writes in response:

I fall into the nostalgia trap sometimes, yearning for something I imagine was more authentic. All of it ten years before my time. Rudy says it was another world, both more and less real than this one. Once I told him I wished I’d been old enough to see it. ‘You’d be dead then, babe,’ he said.

In a preface to an interview with Lippens in Bomb, Kate Zambreno likens his writing to the classics of New Narrative (Lippens even mentions an anecdote about discovering Kathy Acker as a teenager), and I’ve been thinking a lot about the New Narrative writers ever since you pointed me specifically towards them in this context, wondering about what it means to privilege personal and bodily experience above any fabricated sense of narrative structure or “story.” In his “Long Note on New Narrative,” Robert Glück says: “In writing about sex, desire and the body, New Narrative approached performance art, where self is put at risk by naming names, becoming naked, making the irreversible happen—the book becomes social practice that is lived. The theme of obsessive romance did double duty, de-stabling the self and asserting gay experience.” And I love so much about this: writing the self as a kind of performance art; “de-stabling” the self as a way of allowing queerness to assert itself in the text.

Elsewhere in the note, he writes:

By 1980, literary naturalism was easily deprived of its transparency, but this formula also deprives all fantasy of transparency, including the fantasy of personality. If making a personality is not different from making a book, in both cases one could favor the "real contradictions" side of the formula. If personality is a fiction (a political fiction!) then it is a story in common with other stories—it occurs on the same plane of experience. This "formula" sets those opacities—a novel, a personality—as equals on the stage of history, and supports a new version of autobiography in which "fact" and "fiction" inter-penetrate.

Everything in this story happened to me, in one form or another, at one time or another, and the reimagining of these experiences and observations now feels as real and true as my actual memories, which, as any neuroscientist will point out, are themselves the result of an active process of alteration that results in “reconsolidation” … actual events mixed with my imagination and shaped by the long passage of time and its revelations.

I want to go back briefly to the novel that I reviewed and which initially sparked our conversation about queer autofiction. Dorothy Strachey writes in her introduction to Olivia, which is a fictional account of the revelation of her sexuality as an adolescent at a boarding school in France:

How should I have known indeed, what was the matter with me? There was no instruction anywhere. … Yes, people used to make joking allusions to ‘school-girl crushes.’ But I knew well enough that my ‘crush’ was not a joke. And yet I had an uneasy feeling that, if not a joke, it was something to be ashamed of, something to hide desperately.

As Andre Aciman writes in his own introduction to the recent rerelease of Olivia, by way of defending it against possible accusations of plotlessness in a novel that is inherently a “tapestry of tortured, introspective moments,” rather than a conventionally structured narrative:

When intractable feelings are the plot, and when doubt, shame, fear, desire, and hope are at the source of a kind of emotional paralysis rather than of action, what readers respond to is the invitation to recognize in themselves what they’ve always felt but never quite had the time to consider or the courage to confront.

—R

P.S. My copy of Martin and John arrived today!

|

| Photo by Fabio Santaniello Bruun via Unsplash |