Trauma Plots

|

|

|

In The New Yorker, Parul Sehgal writes that the "invocation of trauma promises access to some well-guarded bloody chamber; increasingly, though, we feel as if we have entered a rather generic motel room, with all the signs of heavy turnover."

I am generally sympathetic to Sehgal's complaints here about the ways "trauma" has saturated so many narratives — I've been grumpy about this imprecise, all-encompassing, self-justifying, shallow use of the term "trauma" for at least a decade now, ever since I was introduced to the world of "trauma studies" in literary theory, a field I was particularly suspicious of because, among other things, it didn't seem to understand how fiction works. One way trauma has been deployed has been to indicate Seriousness in novels, a move I've perhaps been especially repulsed by because I find a lot of Very Serious Novels very very uninteresting.

However, for me, Sehgal's outcry is simultaneously (and paradoxically) too precise while being imprecise. This may not be her fault — it certainly is not all her fault — but the fault of hazy concepts and difficult situations dominating American culture at the moment, a culture both energized and muddled. The value of Sehgal's analysis is that it identifies some of the sources of the muddle, even if it misses the energy and maybe even the point.

The first imprecision is Sehgal's definition of "the trauma plot". Here is one attempt she makes:

Dress this story up or down: on the page and on the screen, one plot—the trauma plot—has arrived to rule them all. Unlike the marriage plot, the trauma plot does not direct our curiosity toward the future (Will they or won’t they?) but back into the past (What happened to her?). “For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge,” Sylvia Plath wrote in “Lady Lazarus.” “A very large charge.” Now such exposure comes cheap.

The problem identified here is not the presence of trauma but the revelation of it in a way that "comes cheap". But what does that mean? What would it mean to up the admission fee for the scar museum? Are the sentences before Sehgal's exposure of cheap exposure meant to be critical — is it, for instance, bad to look into the past? Sehgal doesn't elaborate, but instead changes the subject to how watered down the idea of trauma has become in both popular culture and scientific literature. She notes that "The expanded [psychiatric] definition [of post-traumatic stress disorder] has allowed many more people to receive care but has also stretched the concept so far that some 636,120 possible symptom combinations can be attributed to P.T.S.D., meaning that 636,120 people could conceivably have a unique set of symptoms and the same diagnosis."

The expanded clinical definition of PTSD is not a new topic — the article "636,120 Ways to Have Posttraumatic Stress Disorder" appeared in Perspectives on Psychological Science in 2013 and has received hundreds of citations since then, showing plenty of discussion, debate, disagreement. I am not a psychiatrist or strongly interested in arguments about definitions, so will leave all that to other people both more knowledgeable and more passionate than I. I raise the topic because it seems to me that 636,120 people could, indeed, each have a unique jumble of symptoms, that this is a conceivable thing, and that art is the realm best positioned to explore the situation. Rather than dismiss all this as narcissism, quackery, or hucksterism, perhaps we could balance skepticism with generosity and compassion, seeking solidarity and regeneration via some of the best possible tools for that: creative ones. Narrative is especially well positioned to explore the hows and whys and what-does-it-matters of differently similar lives.

One path out of this problem (if it is a problem) — a path I am not going to follow here but which I would be interested in seeing — would be to eschew our current categories and seek other ways of describing experience, of embracing the multiplicity of ways to be shaped by the gravitational force of wounds. Writing this post, I've got stuck in my head the repeated question in a well-known 4 Non Blondes song, that question being What's going on? — a question that art ought to explore.

What's going on?

(Unanswered, nagging, the question naturally led me to the marvelous use of the song in Sense8, itself a beautiful exploration of multiplicity, trauma, solidarity, regeneration, etc. — if this be a trauma plot, more of it, please!)

Still, I think Sehgal is right to point to the capaciousness of what gets called "trauma" and "traumatizing" because saying something is "about trauma" today is like saying you read it on the internet. The statement may be entirely true, but it doesn't actually say much — and by not saying much, it may be misleading.

Some passing comments in Sehgal's essay demonstrate the perils she decries. Her desire to show the ubiquity of stories centered on events declared traumatic and people declared traumatized places a distorting lens in front of a singular book like Yanagihara's A Little Life, which Sehgal quite mistakenly seems to read as work of social and psychological realism. It may be many things, but it is clearly not straightforward realism. In Sehgal's reckoning, trauma narratives are now a genre, which is to say a set of conventions and expectations; her argument is, at least partly, that she finds the genre predictable, repetitive, boring, annoying. Yet in expecting the novel to fit her idea of the genre, she has misread it. This is a danger for any book like A Little Life, playing with, expanding, subverting genre conventions, because readers may not see the play, the expanse, the subversion and instead see only failure to provide the kind of experience the genre has trained them to desire.

To the extent that it is a trauma narrative, A Little Life does what the greatest genre fictions do: it invokes the genre for the sake of pushing it beyond its boundaries, using its audience's expectations as tools for surprise and reflection. Sehgal says she wants fiction that allows room for the reader, but A Little Life does that, asking us always what we desire from stories and people, what we imagine the world to be, what we are willing to believe and, most importantly, to feel — then all but screaming at us to reflect on the feelings the book provides, to learn from that reading experience. This is the technique of maximalism, of overloading readers so that we ask ourselves, 4 Non Blonde-like, "What's going on?" (I have made this same argument about Woolf's The Years a few times in relationship to the genre of the family novel. Like A Little Life, The Years is a book that tends to make critics' brains explode because they want it to fit their ideology, their set idea of the author, their own emotional life ... and it refuses, giving them both too much of what they don't want and not enough of what they do. Yanagihara's success especially invites this — witness Andrea Long Chu's recent attack. Chu sees some of what A Little Life is up to, but it all annoys her so much that she can't help but get all ad hominem about it, producing less criticism than whine. Chu is good at snark, so she gets published and has a fanbase, but were we to read her in the way she reads Yanagihara, the portrait would hardly be flattering.) What Yanagihara does is bring to the trauma narrative many tools from other forms, the gothic novel and melodrama most obviously. (The monastery makes the gothic label unavoidable.) Categorizing A Little Life uncomplicatedly as a trauma narrative is about as useful as doing the same for one of Fassbinder's melodramas.

Before I would call it a trauma narrative, though, I would call A Little Life a horror novel, one that has some elements in common with Stephen King's It and some of Peter Straub's books, among many others. (Indeed, one of the only novels I've read that approaches the emotional effect of A Little Life on me is Straub's Koko, a very different book but one that similarly understands how pain and horror persist, and how that persistence shapes lives. It, too, uses the gothic and melodramic for rich purposes.) Horror, in fact, might be said to be the genre of trauma, but it, too, can be reduced by conventional approaches to trauma rather than allowing the representation of trauma to explode all the boundaries.

In the realm of film, Willow Catelyn Maclay is the critic doing the most sustained work I know about how form, plot, characterization, and theme work together, for better and worse, in trauma narratives. See her review of The Invisible Man or of Swallow, wherein she writes, "There’s a liberal back-patting to much of modern horror-adjacent filmmaking that I find almost entirely useless, because filmmakers seem to be afraid to claw beneath the surface and discover something rabid and feral about womanhood." Or her review of Saint Maud: "The modern horror film is likely too infatuated with psychological realism to appeal to me entirely. The lingering scar-tissue of traumatic events has always part of the genre, but the modern horror film oftentimes dwells in the aftermath of inciting events instead of the moment of rupture in the psyche." Or her very personal, powerful exploration of Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks. As I've said before, Maclay's writings on the films of Rob Zombie, particularly Halloween II, are among the very small set of contemporary critical writing on horror that I most appreciate, and it is in her writings on Zombie that she really gets at the difference between powerful, unconventional trauma narratives and all the others. For instance: "There’s a reverberating ache at the center of Rob Zombie’s movies that I find comfortable to exist within because his movies are honest about the pain that comes with having experienced violence and loss. ... He shows you the effects that this violence has on people who survived. People who now have to live in the aftermath of monsters whose images never die and the victims who fade into dust."

Maclay is smart about the failure of so many horror and trauma narratives being not the presence of traumatic backstory but the timid use of it. I am fully with her in feeling that standard realism in inadequate to the task. This is what Sehgal, who seems committed to an idea of literary fiction that I have little interest in, can't really reconcile. In thinking about how Virginia Woolf's imagined Mrs. Brown might be rendered by a writer today, Sehgal proposes:

We’d meet her, I imagine, in profile or bare outline. Self-entranced, withholding, giving off a fragrance of unspecified damage. Stalled, confusing to others, prone to sudden silences and jumpy responsiveness. Something gnaws at her, keeps her solitary and opaque, until there’s a sudden rip in her composure and her history comes spilling out, in confession or in flashback.

I chuckled in recognition of exactly this tendency. Sehgal is very good at identifying a flavor of contemporary writing. Spot on. Yet what is the remedy? At the end of the essay, Sehgal writes, "The trauma plot flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom, and, in turn, instructs and insists upon its moral authority." I have no disagreement with that except that I don't think the problem is a focus on trauma; the problem is conventional, clichéd writing. That's not trauma's fault.

Trauma, as Freud knew, is too big for us to contain. A narrative that doesn't admit this is rendered small by its use of traumatic material and traumatized characters. The challenge is what it has been ever since fiction coalesced into a mode of writing, and particularly once psychological realism took hold in the 19th century. Any narrative with faith that a character's traumatic backstory is alone sufficient for a story is a narrative that is smaller than the events it portrays, a narrative that pretends it is possible for a chart of cause and effect to map the way to peace and justice. Recognizing this limitation is one thing that has fueled innovative writing for well over a century.

The trauma narratives that work are ones written by people like Yanagihara who know that trauma is a diva and a drama queen, that it wants all the attention, all the time, and all the air in the room. Simply depicting trauma is no more powerful than a candle in the ocean. Exploring it, though — using violence, horror, madness as material for art — allows the ocean's depths to reveal themselves and us to find our myriad ways through them.

|

Parul Sehgal is not Arlene Croce, by any means. Nonetheless, the fear of art being evaluated for reasons other than aesthetic ones haunts her essay. This is apparent in her struggle to make an aesthetic argument against A Little Life:

Trauma trumps all other identities, evacuates personality, remakes it in its own image. The story is built on the care and service that Jude elicits from a circle of supporters who fight to protect him from his self-destructive ways; truly, there are newborns envious of the devotion he inspires. The loyalty can be mystifying for the reader, who is conscripted to join in, as a witness to Jude’s unending mortifications. Can we so easily invest in this walking chalk outline, this vivified DSM entry? With the trauma plot, the logic goes: Evoke the wound and we will believe that a body, a person, has borne it.

What can a reader who is not mystified make of this? Jude is, indeed, a galling, frustrating character, but I had no trouble beliving in him, indeed believed in him more deeply than almost any other character I have ever read. This is true for other readers for whom the book is powerful, just as Sehgal's reading is true for many readers who do not connect with the book. What of us? What of them? It's a tremendously divisive novel. What's going on?

In a lot of criticism like this, the desire — our desire (because I, too, have felt it with books I didn't like but other readers felt passionately about) — to accuse the text and, often, the writer of false consciousness, of impure motives, of exploitation and abuse of the reader leads to a desire to locate in the writer, the book, and sometimes its appreciators a failing. Especially if you strongly dislike a book (or movie or music or whatever), it can be difficult to imagine that other people honestly do. We turn around our sense of our own failure and project it onto others. The work itself becomes not an imperfect item that some people love and some don't; it becomes a plot against the person making the criticism and the criticism a weapon of truth, justice, and ego-preservation. There, perhaps, is the trauma plot.

Clearly, Sehgal feels herself to be superior to the narratives she identifies as suffering from the trauma plot. She needed to write this essay to try to express, but also perhaps to analyze, her sense of superiority, which is also a sense of being left out. If this is so popular, and lots of other people love it and I don't, what is wrong with me? I know that feeling well! Our ego then moves us toward: How can I show that everybody else is wrong and I am right?

"I am the good one here," ego says. It is a whisper I have learned to be wary of.

Sometimes, maybe you are the good one here. Maybe you have been blessed with some special strength to overcome the weakness that leaves the rest of us among the fallen and unenlightened. But I can't help wonder what a more generous version of Sehgal's essay might have been. It wouldn't have had to be less critical, perhaps, but instead might have begun from a more open, less condemnatory starting place, a place that allowed her to develop her theories rather than shotgun them against a monster of her own devising. What if she started from a premise that left room for the possibility that she is wrong and that this thing she sees as being so prevalent and popular is prevalent and popular not for a reason of dishonesty or stupidity or malice but rather because it meets a need that she does not share. Ego tells us that the needs we don't share are beneath us and bad, but we don't need to listen.

What if we at least began from a less sanctimonious and self-righteous premise and assumed, instead, both intelligence and good faith in the people who appreciate what we do not? How might we move forward if our inquiry began not from, "What is wrong with everybody else?" but rather "What is wrong with me?"

What is wrong with you?

What's going on?

Answer honestly and you might discover that the motel room has revealed itself to be a bloody chamber.

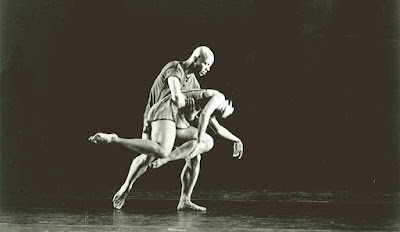

images: 1. photo by Jordan Madrid on Unsplash, 2. Marina Reich on Unsplash, 3. Still/Here, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, 4. Psycho