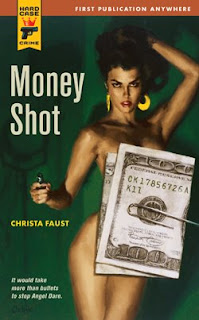

Money Shot by Christa Faust

I confess: I like the idea of noir novels more than I tend to like noir novels themselves. (Noir movies I often enjoy watching, but there are few I've found very memorable, for whatever reason.) In fact, I don't much like mystery novels of any sort, though I've read a lot of them in a desperate attempt to like them more. I've tried at least one novel by all the classic mystery writers I know of, and the only such writer I've managed to read more than one book by with any pleasure is Patricia Highsmith. I've tried contemporary mysteries by a bunch of different writers, but hardly any of them have remained in my memory. I don't know all the reasons for my inability to really embrace mystery and crime novels -- strange, I think, given my interest in the psychology and sociology of violence -- but I think most of it comes from my general indifference to plot. I like books that have some sort of narrative, certainly, but I don't generally care for books where plot is the primary element.

I confess: I like the idea of noir novels more than I tend to like noir novels themselves. (Noir movies I often enjoy watching, but there are few I've found very memorable, for whatever reason.) In fact, I don't much like mystery novels of any sort, though I've read a lot of them in a desperate attempt to like them more. I've tried at least one novel by all the classic mystery writers I know of, and the only such writer I've managed to read more than one book by with any pleasure is Patricia Highsmith. I've tried contemporary mysteries by a bunch of different writers, but hardly any of them have remained in my memory. I don't know all the reasons for my inability to really embrace mystery and crime novels -- strange, I think, given my interest in the psychology and sociology of violence -- but I think most of it comes from my general indifference to plot. I like books that have some sort of narrative, certainly, but I don't generally care for books where plot is the primary element.And yet I loved Christa Faust's recent novel Money Shot.

I'd been intrigued by the Hard Case Crime series for a while. Their retro covers appealed to the part of me that revels in the pulp era, and everything I'd read about the series indicated that it was thoughtfully edited. I decided to start with Money Shot because I was curious to see how the first female writer in the Hard Case series would handle a story about the porn industry.

Because I am not a good reader for the mystery/crime genre, I can't tell you whether this is a good mystery/crime novel. What I can say is that it overcame my prejudice against plot-heavy books by being somewhat more about its main character than its plot. The basic plot, in fact, seemed fairly standard and predictable to me, but this seemed more like a virtue than a flaw, because if the plot had been too clever or complex, the novel's strengths might have been less prominent. Its strengths are the development of the main character, Angel Dare (a retired porn actress), and the presentation of what everyday life in the world of porn is like. I have no idea how accurate Faust's presentation of porn life is, but that doesn't matter -- what matters is that it was portrayed with so many well-chosen details that it was convincing and vivid. All the accuracy in the world is useless if a writer doesn't know how to select and present details to create verisimilitude. Most good fiction writing, regardless of genre, requires some worldbuilding skills, because even if the story is set in a real place, fiction is just a representation of a conception of that real place, and the best "realistic" fiction has as much care for rendering an imagined place in the reader's mind as does the best science fiction set on alien worlds.

The basic story of Money Shot is almost Existentialist -- Angel Dare's life is quickly destroyed for reasons she doesn't understand. The story is not Existentialist, though, but rather conservative in that the forces destroying Angel's life turn out to be identifiable; there are reasons her life is destroyed and there are people who committed various actions that come together in a web of cause and effect to cause the destruction. Everyone has a motive and once all the complications get explained we can understand why the various characters behave in the ways they do. Generally, I hate such stuff, because it seems reductive, dull, and untrue to my own experience of life. But I found Angel Dare's character and situation interesting enough that I mostly ignored the justifications for the actions, and so the narrative became, in my mind, a more complex and ambiguous one than its surface presented.

It helps that Christa Faust has a good sense of prose rhythm and pacing. She doesn't write "transparent prose" (the thin gruel offered by the anti-art workhouse), but she also doesn't indulge in the strained metaphors and clunky sentences that so many writers seem to think necessary for a novel to truly be noir. Angel's personality comes through the narrative voice Faust creates for her, and though it occasionally offers too many clichés for my taste, on the whole this voice is precise and engaging:

I normally hated that Men-Are-From-Mars, testosterone-driven impulse boys get where they want to solve all my problems by troubleshooting me like buggy software and offering up a simple concrete solution to stop my tears. But if Malloy had done something more intuitive and nurturing like hugging me or telling me everything was going to be all right, I would have disintegrated into a useless puddle. His simple answer to the problem of the big shoes gave me something to hold on to. Payless. Right. Good idea. It allowed me to pretend that the lack of shoes that fit really was the reason I was crying.This is not a paragraph that will blow anyone away as Great Writing, but it is clear and efficient, and with that clear efficiency it conveys a few things in a short space -- it presents the complexity of Angel's feelings about men and masculinity, it conveys her emotional state at a vulnerable moment, and it shows us a little something about Malloy, one of the other important characters in the book. It's specific and it has the feel of originality, of something necessary to this character at this place in this time, without drawing us out of the story and situation by calling lots of attention to itself (which is a perfectly good technique in the right sort of book).

The ending of Money Shot is somewhat tame in comparison to the fatalism leading up to it, but I found it -- again, against all odds -- satisfying and even somewhat moving. The second half of the book is brutal, but it is a logical brutality, not a random one, and the conclusion brings the brutality to a close without offering any easy answers or simple morality, because what remains behind it all is the destruction unleashed on Angel's life, and no matter what happened to her in all the possibility ways Faust could have ended the book, that destruction would never be able to be assimilated into a simple conclusion. Revenge may be had, the law can do its thing, and loose ends can be tied up ... but the dead are still dead, and lost illusions and shattered dreams don't recover well. The great revelation at the end of the book is that we realize to what extent the whole tale has been a meditation on the implications of the first sentence:

Coming back from the dead isn't as easy as they make it seem in the movies.