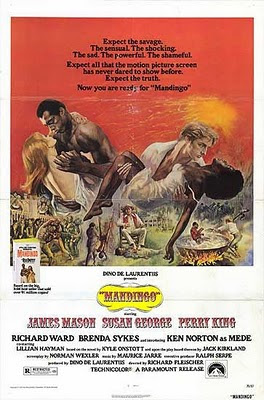

Mandingo

When it first came out, many critics loathed Mandingo. They said it was a pulp potboiler, a racist exploitation film, softcore porn, immoral. Roger Ebert gave it zero stars and called it "a piece of manure" and "racist trash". It did just fine at the box office in 1975, the year it was released, but its reputation as laughably and/or offensively awful stayed with it, keeping it out of circulation for a long time. It's only been generally available on DVD for a couple of years now.

for a couple of years now.

In 1976, Andrew Britton wrong a long and careful vindication of the film, but his essay was not widely read. Britton noted how many of the reviewers didn't seem to have paid much attention to the film itself, given how many simple errors about the plot and character relationships filled their reviews. More famously (if academic press books by film scholars can qualify as "famous"), Britton's teacher and colleague Robin Wood devoted a chapter of Sexual Politics and Narrative Film to Mandingo, which is where I first heard about the movie.

to Mandingo, which is where I first heard about the movie.

After watching Mandingo, I wanted to see if anybody had written about it more recently, especially within the film blogosphere, and that's when I discovered some real gems. I can't say I loved the film in the way some people have, but I certainly think the original critics who hated it missed the mark completely. It's a remarkable corrective to and comment on such things as Gone with the Wind, and some moments reminded me strongly of Gillo Pontecorvo's Burn!, particularly in the way both movies complicate the viewer's sympathies for the white protagonist.

But my purpose here is simply to point you toward some excellent online writings about the film:

"The Eyes We Cannot Shut: Richard Fleischer's Mandingo" by Robert Keser:

In 1976, Andrew Britton wrong a long and careful vindication of the film, but his essay was not widely read. Britton noted how many of the reviewers didn't seem to have paid much attention to the film itself, given how many simple errors about the plot and character relationships filled their reviews. More famously (if academic press books by film scholars can qualify as "famous"), Britton's teacher and colleague Robin Wood devoted a chapter of Sexual Politics and Narrative Film

After watching Mandingo, I wanted to see if anybody had written about it more recently, especially within the film blogosphere, and that's when I discovered some real gems. I can't say I loved the film in the way some people have, but I certainly think the original critics who hated it missed the mark completely. It's a remarkable corrective to and comment on such things as Gone with the Wind, and some moments reminded me strongly of Gillo Pontecorvo's Burn!, particularly in the way both movies complicate the viewer's sympathies for the white protagonist.

But my purpose here is simply to point you toward some excellent online writings about the film:

"The Eyes We Cannot Shut: Richard Fleischer's Mandingo" by Robert Keser:

Without sentimentality or official pieties, Fleischer uses an unbridled and passionate melodrama to lay bare how slavery, the economic enterprise that turns humans into commodities, could not but distort the entire web of human relationships enabling it. To appropriate a phrase by John Berger from another context, Mandingo uniquely serves as “the eye we cannot shut”, the persistent vision of competing powers – the slave’s physical strength (and by extension sexual potency) against the master’s sovereign power to define reality and decide life or death.Dennis Cozalio at Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule, on why the film is among his top 100:

When I saw the movie at the American Cinematheque early last year, it was easy to sense that the audience came primed to giggle at the antiquated, period-authentic dialogue, the impolitic slurs and the debased folk mythology that makes up the worldview of Mandingo’s white characters. But it was heartening to hear that nervous giggling die down after about 15 minutes when it became clear that the movie was no corny sex-and-slavery romp, was no easy candidate for Mystery Science Theater-type derision, but instead a serious and agonized attempt to grapple with a period in American history that it seemed was still too hot to handle. Director Richard Fleischer’s unadorned, direct style is the perfect approach to this material, and the result is a movie that gets under the skin of blacks and whites, in 1975 and in 2008, and lives there, coalescing into a depiction of our country’s subconscious, as likely as any depiction of its subject ever made to claim authenticity, genuine insight into the way things must have been.And, from an essay that belongs with Britton's and Wood's as not only a model of how to approach Mandingo, but as a model of film writing in general, Timothy Sun at Not Coming to a Theater Near You:

Much of the derision aimed at Mandingo comes from a belief that what it depicts is so outrageous that it cannot be true, it must be comedy. Certainly, the performances, particularly those of James Mason and Susan George, are over-the-top – in the case of the latter so much so that it often veers into camp – but I think Fleischer knows exactly what he is doing. Throughout the film there are acts of racism so unfathomable to a modern audience that they appear totally absurd: to cure his rheumatism, Papa Maxwell places a young slave boy at his feet while in bed, pushing against the boy’s the stomach in order to flush the pain out of his own body and into his; the same boy is seen time and time again lying flat on the ground while Maxwell uses him as a foot stool; Mede is forced to toughen his skin before a big fight by sitting in that aforementioned cauldron of hot water; etc. To see these images is a surreal experience, but that does not mean they did not occur. Moreover, whether or not the specific offenses that the film depicts actually took place is not really the issue; I have no doubt that if they did not, something equally horrible, if not more so, did. If there is anything the history of humanity has taught us, it is that there is no end to the sadistic imagination. The audience I watched the film with chuckled throughout, whether it be at the sight of the boy absorbing rheumatism or a line like, “Niggers don’t feel pain as fast as white folks.” I don’t believe this laughter comes from any sort of innate racism or lack of compassion toward the slaves, but rather from a lack of any sort of apparatus with which to understand how something like this could have occurred. We are taught in schools and through cultural osmosis that the slaves were whipped and forced to do backbreaking work, but the extent to which they were simply used as sub-human property – to breed, to fight, to fuck – the exceedingly intimate way blacks and whites constantly interacted as abuser and abused, is (hopefully) not something a modern mind can comprehend. So, we laugh. Fleischer understands this and purposely heightens the already extreme offerings that much further, pushing the idea that a society that can do these things is indeed absurd. There are several small, throwaway scenes and images that highlight the underlying surrealism of what we are seeing, most memorably for me a quick tracking shot of a group of chained slaves marching in line with two slaves in front playing Yankee Doodle on a fiddle and waving a giant American flag to keep time. In this context, the performances of Mason and George, who play the two most virulently racist characters in the film, are exactly as they should be, highlighting the bewildering absurdity that slavery and racism require to thrive.

An interesting comparison can be made to a film like Schindler’s List, where the crimes it forces us to watch are just as terrible and absurd but because the events are relatively recent and well documented, the audience believes and shudders in horror. Schindler’s List also has the advantage of being shown from the point of view of an outsider; every time Ralph Fiennes commits some random act of violence, we get a reaction shot of Liam Neeson quietly outraged, effectively dictating and channeling the audience’s own reaction. To further the distancing effect, the film is shot as if it were a historical document, leaving the audience no melodramatic rack to hang its emotions on (and denying the overwhelming visceral impact of a color Holocaust); instead, the emotion comes flooding through unfiltered at the sight of the direct image. In this way Schindler’s List continues in the line of historical filmmaking that serves a national and cultural interest, creating a master narrative where good trumps evil and audiences can be entertained without feeling sullied; this is not to say that its history is whitewashed in the same vein as Gone With the Wind, but it is made palatable. The film is beautifully and elegantly shot, the tone is solemn and programmatic, the hero is someone who does what we would like to believe we would have done. Mandingo, as should be clear by now, eschews this approach. There are no heroes, there are no real villains, the physical and verbal abuse meted out to the slaves is so nonchalant and amoral that, again, the audience almost has no option other than to laugh.