Leon Morin, Priest

Melville was a king of style, his best films usually tales of gangsters who are looking for a portal back to the Hollywood movies they fell out of. Leon Morin, Priest, though, is the middle of a trilogy of movies in which Melville tried to capture the experience of France during World War II, a time when Melville himself had been soldier in the Resistance -- the first, The Silence of the Sea, was his first feature as director, the third, Army of Shadows, is his most epic masterpiece, the film where he was able to bring together all of his interests, passions, and proclivities, giving them a depth and resonance they'd not quite had before.

Leon Morin was originally going to be more epic than it is, but part of Melville's goal in making it was to create a more commercial and popular movie than he had before, and so he sacrificed as much as he could bear to that goal. His first cut ran about three hours, whereas the new U.S. edition from Criterion runs 117 minutes. What Melville reportedly cut -- and this is supported by the two (tantalizingly short) deleted scenes included on the Criterion disc -- was a lot of material about everyday life in France during the Nazi occupation. The released version of the film focuses primarily on the protagonist, Barny (Emmanuelle Riva), and the object of her fascination, the priest Leon Morin (Jean-Paul Belmondo). Traces of the cut scenes haunt the film in a few anomalous and inexplicable moments, but these contribute to the overall feeling of the occupation's remote terror, like the sounds of tanks and gunshots just beyond Barny's window at night. Mostly, this is a movie about Barny's loneliness and the emotional perils that loneliness brings her to.

Unlike every other Melville film I've seen, and despite its title, Leon Morin, Priest is the story of a woman. In terms of gender, it is the inverse of Melville's typical worlds -- worlds of men in which a few women wander around as sources of mystery, objects of fascination, causes of chaos or confusion, items of inscrutability. Here, in a world where most of the men have gone off to the woods, Leon Morin is the inscrutable object of desire. He begins as Barny's fascination alone, but as she introduces more of the town's women to him, it seems as if he becomes the substitute husband, father, and devil to them all. They visit him in his ascetic upstairs lair, a place that looks like many of the ruffian hide-outs in Melville's crime movies.

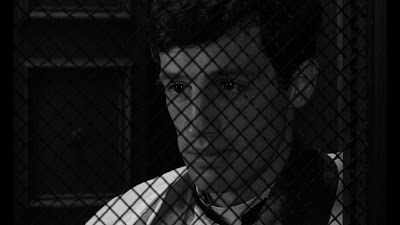

Melville first wanted to film Leon Morin, Priest when he read the novel by Béatrix Beck soon after it came out in the early 1950s, but he said he waited until he could find just the right actor for the title role, and he didn't find that actor until he saw Belmondo working on Breathless (in which Melville had a cameo). Not everyone would see an actor brilliantly portraying a nonchalant gangster and think, "Oh, he'd make a marvelous priest!", but we should be grateful for Melville's odd eye, because Belmondo's performance as Morin is extraordinary. It's a role that could have been either dull or campy, but Belmondo brings many levels to it, and his inherent charisma and sexiness help us see how alluring and frustrating he is to the town's women. If we are able to participate as fascinated and even desiring spectators, we are then in the position of Barny and the other women. We, too, would want to bring all our problems to Leon Morin. We, too, would want to go Christian for him.

But the wonder of Belmondo's performance is not simply a result of his physique and presence. The wonder comes from the balance he finds between tenderness and arrogance. He fills Morin with the unconquerable confidence of the true believer, of the person who is able to admit all the possibilities of doubt because he has answered them for himself and knows that his path is the righteous one. Morin is someone we can desire as friend or fantasize as lover, but in Belmondo's performance he is also someone who vividly enacts the psychopathology of the priesthood.

It's interesting that Leon Morin received good notices from the Catholic and right-wing press when it was released, and was denounced by the Communist and left-wing press, because though it is full of Catholic words, Morin comes off a bit like the title character in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. Viewers who do not hold as much antipathy towards priests as I do would likely make a less criminal comparison, but I can't conceive of interpreting the events and images of the film in any way that offers Morin (or his faith) as good news. We can sympathize with Barny, certainly, and Melville makes hers the perceptions that shape our viewing, but the final scenes are ones in which she is to be pitied and we are to regret all of our attractions to Morin and his pieties. All of the energy Barny expended on Morin, all of the time and thought and emotion she gave to the faith he led her to, brings her nothing but grief. She was a collaborator in the occupation of her mind and desires by a predatory man who used his attractiveness, intelligence, and authority for the sole purpose of luring people into his cult and making them submissive to his power.

Think of how much better of Barny would have been if she had been able to follow through with her desires for Sabine, a woman in her office who seems to share at least some of Barny's interest in her. Morin congratulates Barny when she says her desire for Sabine has ebbed, and he deliberately uses his own attractiveness to bring Barny closer to what he sees as the righteous path of heterosexual desire. His arrogance is breathtaking. He wants power over the women he encounters, he wants control over their lives, and he revels in the spell he casts. He justifies all of his awfulness by telling himself he's doing it for God.

Emmanuelle Riva's performance as Barny is as rich as Belmondo's as Morin, but inevitably less spectacular because Morin is the focus of eveyone's attention. Watch Riva's eyes -- the character of Barny may be plain and somewhat lacking confidence or conviction, but Riva's eyes suggest the character represses her strength and solidity, letting them fuel her in the way that Morin's repressed sexuality fuels his faith and violence (note how often he pushes Barny as if she's a piece of furniture).

In a scene toward the end, Morin visits Barny at home and takes over the job of chopping wood, a chore she's been doing just fine. He shows how strong and macho he is, and then she takes back the axe and slams it into the stump. Morin can't leave it there, though, and takes it out for examination and, apparently, fixing (like a non-Catholic woman, it doesn't meet his standards). Barny then asks him if he weren't a priest if he would marry her; he laughs the question off, she asks again, he gets angry, and he furiously smacks the axe into the stump and storms out of the house. "His hand," Barny says in a voiceover, "in a single gesture, had given all and taken all away."

Apparently, in the original novel, Morin at this moment answers Barny's questions about marriage by saying, "Yes," but Melville wanted something more ambiguous. We do not know why Morin becomes so angry, though Barny seems to think it is because he wants to say yes and cannot. But that does not have to be the only answer. His fury could stem from his recognition of failure -- that he has tried to use his power over her to bring her, as Trent Reznor might say, closer to God. He also wants to enact the role of the good, masculine husband -- here she is raising her daughter, running a household, holding down a job, and he could step in as the patriarch and put her into her more proper place of motherly housewife -- he could, were he not a priest, take the axe out of her hand every day. He has failed at all of it. In that moment, he at least partly wants to sink the axe in her skull. (But though he may share certain traits with Henry, he is only a serial killer of dreams and desires, not bodies.)

As much as we pity Barny at the end of the film, we should celebrate for her, too -- she is free of this priest, and she will likely be more wary of such men in the future. Perhaps she'll return to her previous atheism. Perhaps she'll seek out Sabine again, or someone similar, someone who won't take the axe away and want to bury it in her brain. The sequel to Leon Morin, Priest, could, in fact, be a feel-good movie called Barny the Lesbian Atheist.