Warrior Dreams and Gun Control Fantasies

Yesterday's massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School was the sixteenth mass shooting in the U.S. in 2012.

Looking back on my post about "Utopia and the Gun Culture" from January 2011, when Jared Loughner killed and wounded various people in Arizona, I find it still represents my feelings generally. A lot of people have died since then, killed by men with guns. I've already updated that post once before, and I could have done so many more times.

Focusing on guns is not enough. Nothing in isolation is. In addition to calls for better gun control, there have been calls for better mental health services. Certainly, we need better mental health policies, and we need to stop using prisons as our de facto mental institutions, but that's at best vaguely relevant here. Plenty of mass killers wouldn't be caught by even the most intrusive psych nets, and potential killers that were would not necessarily find any treatment helpful. Depending on the scope and nuance of the effort, there could be civil rights violations, false diagnoses, and general panic. (Are you living next door to a potential mass killer? Is your neighbor loud and aggressive? Quiet and introverted? Conspicuously normal? Beware! Better report them to the FBI...)

That said, I expect there are things that could be done, systems that could be improved, creative and useful ideas that could be implemented. I'd actually want to broaden the scope beyond just mental health and toward a strengthening of social services in general. I'm on the board of my local domestic violence/sexual assault crisis center, where demand for our services is up, but we're hurting for resources and have had to curtail and strictly prioritize some of those services. It's a story common among many of our peers not just in the world of anti-violence/abuse programs, but in the nonprofit social service sector as a whole.

What we have is a bit of a gun control problem, a bit more of a social services problem, and a lot of a cultural problem.

One of the best books I've encountered on this subject is James William Gibson's Warrior Dreams: Paramilitary Culture in Post-Vietnam America. It's from 1994, but is in some ways even more relevant now.

Gibson ends a chapter called "Bad Men and Bad Guns: The Symbolic Politics of Gun Control" with these words:

To argue ... that many of these murderers could have been stopped solely by increased gun control is to pretend that the social and political crises of post-Vietnam America never occurred and that the New War did not develop as the major way of overcoming those disasters. Paramilitary culture made military-style rifles desirable, and legislation cannot ban a culture. The gun-control debate was but the worst kind of fetishism, in which focusing on a part of the dreadful reality of the decade — combat weapons — became a substitute for confronting what America had become.We seem to be a generally less violent country than in the past, and yet this specific type of crime (mass killing) is on the rise. Coverage of killers in the media certainly adds to the attraction of these acts for people who seek such glory. More broadly, mass killings such as this should cause us to consider hegemonic masculinity, a culture of child-killing, and the privileges of white male terrorists. (Those last 4 links via Shailja Patel.) We should remember that the President who shed tears for the deaths of children in Connecticut authorized drone strikes that have killed many times more children.

The desire to get rid of all the guns is understandable, but it is useless and counterproductive. 300 million (or more!) guns aren't going away, sales have been strong for at least 10 years, with at least 1 million guns sold legally every month (good luck finding reliable statistics on illegal guns).

Meaningful policy needs to be pragmatic. We've got tons of laws already. Additionally, the utopian desire to get rid of all guns only plays into the paranoid narrative the NRA uses to keep fundraising strong: "The liberals want to take your guns! Send us money to stop them! Meanwhile, stockpile because the liberals always win and they're going to ban all gun sales next week!"

Many people have called for a renewal of the assault weapons ban. I expect the gun manufacturers would be thrilled. First, because it would incite panic buying. Second, because it's primarily based on particular rifles' aesthetics, and the last time the ban was in place, the manufacturers found easy loopholes. So they get the best of all possible worlds: increased demand, which allows them to raise prices on items they've already manufactured, and then relatively easy design changes that don't cost them a whole lot of money and still allow them to sell lots of guns. Indeed, if anything, the ban increases the aura around such weapons, making them even more desireable to would-be killers. The NRA would love it, too, because they would finally be able to pin some actual gun control measures on the Obama administration, and their fundraising would skyrocket. They'd never say it publicly, but the gun industry and the gun lobby might as well stand there just waiting for the assault weapons ban to be renewed, saying, "Go ahead. Make our day."

Probably the most practically effective part of the ban has nothing to do with the guns themselves, but rather how much ammo they can hold before reloading: the magazine capacity limits. Ban all magazines beyond a certain capacity and no matter how scary the gun looks or how light the trigger action is, it's not going to be able to fire lots of bullets. To control guns in the US most effectively may mean controlling not the guns themselves so much as their components and ammunition.

Which brings us to a worthwhile question: What sort of practical gun policies might have prevented what happened in Newtown, Connecticut? The sad, frustrating answer seems to be: maybe none. Even a fantastically perfect system for preventing potentially mentally ill people from buying guns wouldn't have worked: the killer used his mother's guns. She bought them legally. She could, presumably, pass any background check. I'm all for better funding and implementation for the background check system, but let's not pretend it would have done anything in this case.

What about bans on high-capacity magazines? That has more potential. Such magazines would still exist, so the effect of a ban would not be immediate. It would have been entirely possible for the killer's mother to have some high-capacity mags that she'd bought some time before the ban, or bought second-hand. There are hundreds of thousands, or perhaps millions, of such magazines out there. Even a draconian confiscation system wouldn't eradicate all banned magazines; it would create a black market. Still, we know from experience that high-capacity magazine bans do generally cause prices to rise and supply to fall.

Then there are the arguments from the other side of the issue: More guns! (See also: James Fallows.) If you don't regularly spend your time among the core gun-rights-at-all-costs activists, you might think such a suggestion is a joke. It's not. It's the only direction in which the absolutist philosophy of the NRA, Gun Owners of America, and similar groups can go. And there's a core of a truth-like substance to it: crime rates generally have been falling. (But individual gun ownership may also be falling. See also this new analysis by CNN, which shows that what we have are more guns in fewer hands.) The fundamental problem with the MORE GUNS! argument is that it is based on a wild west mystique that assumes far too much competence among people in crisis moments and ignores how easy it is for mistakes to become deadly when guns are involved. Even if the premises of the argument were reasonable and desireable, it doesn't take a lot of deep thought for the practicalities to show their problems.

That's not to say that people don't successfully defend themselves with guns, or reduce the number of casualties in some situations, or even that the presence of guns does not deter some crimes. In plenty of such situations, though, if everyone were armed, the likelihood of the moment escalating into total, even more deadly chaos would increase. I'm completely in favor of more gun safety training (in a nation of guns, it makes sense for as many people as possible not to freak out when they encounter one), but I don't want to live in a world where everybody feels the need to be armed.

An important point to note, though, is that the current situation didn't just pop up out of nowhere. It was constructed over the course of decades, and the NRA is partly to blame. But they couldn't have done it alone.

There's an insightful post at Talking Points Memo, a letter from a reader who, much like me, grew up in the gun culture. The reader notes the rise in popularity of military-style weaponry since the mid-1980s.

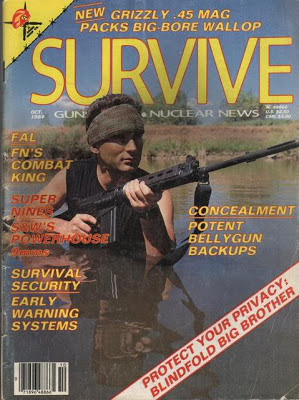

I can’t remember seeing a semi-automatic weapon of any kind at a shooting range until the mid-1980’s. Even through the early-1990’s, I don’t remember the idea of “personal defense” being a decisive factor in gun ownership. The reverse is true today: I have college-educated friends - all of whom, interestingly, came to guns in their adult lives - for whom gun ownership is unquestionably (and irreducibly) an issue of personal defense. For whom the semi-automatic rifle or pistol - with its matte-black finish, laser site, flashlight mount, and other “tactical” accoutrements - effectively circumscribe what’s meant by the word “gun.” At least one of these friends has what some folks - e.g., my fiancee, along with most of my non-gun-owning friends - might regard as an obsessive fixation on guns; a kind of paraphilia that (in its appetite for all things tactical) seems not a little bit creepy. Not “creepy” in the sense that he’s a ticking time bomb; “creepy” in the sense of…alternate reality. Let’s call it “tactical reality.”Some of these people are my friends and acquaintances; indeed, when I inherited a gun shop and got an FFL to sell off the inventory, I sold some of those tactical guns to my friends, the fetishists. I certainly don't think they'll go on a rampage, but I do think they live in an alternate reality — a reality my father was very much part of, where black helicopters fly over the house to spy on us, where conspiracies and threats lurk in every social crevice, and where anybody without a bug-out bag is a moron who will die in the ever-impending apocalypse.

The TPM reader who notes this proposes the change in US culture happened sometime between 1985 and 1995. It's probably a few years earlier, but in general that seems right to me (and fits with the information and argument in Warrior Dreams). It was in the early 1980s that my father started selling fully-automatic machine guns, then moved to primarily military-style semi-automatics after the 1986 Firearms Owners Protection Act banned the civilian ownership of new machine guns and added a lot of regulation and taxes to existing machine guns, turning them essentially into collectors' items (many cars are cheaper to buy than a legal machine gun these days). Business was very good for a while, and the threat of the assault weapons ban helped sales considerably. When the ban was in place, those guns became even more desirable — much like banned books or banned movies, once somebody says, "No, you can't have that!" then people who never wanted it before suddenly become interested.

I haven't been able to find any reliable statistics on gun sales in the 1980s (good data on gun sales isn't easy to get, for various reasons), but 1984/1985 seems plausible as a critical mass point for the shift in gun culture — conservatives' push within the NRA to shift the organization's tone and political attitude had succeeded*, Reagan was President (the first President endorsed by the NRA), TV shows like The A-Team and Airwolf were popular, G.I. Joe and other military comics were common, various paramilitary books and magazines filled newsstands, and Hollywood had started making movies like Red Dawn and Rambo II.

The last fact is significant. When Dirty Harry came out in 1971, sales of the Smith & Wesson Model 29 increased significantly. But that was just a big revolver. In 1985, Rambo II seemed to do wonders for sales of the H&K 94 and MP 5. Warrior guns.

It would be facile for me to end by pretending I have any easy or immediate solutions. I don't. Perhaps we need some feel-good measures, but I fear they make us think we've accomplished something when we haven't. There's a strong desire right now, it seems, to do something. But symbolic laws and security theatre won't help us.

Here's the final paragraph of Gibson's introduction to Warrior Dreams:

Only at the surface level, then, has paramilitary culture been merely a matter of the "stupid" movies and novels consumed by the great unwashed lower-middle and working classes, or of the murderous actions of a few demented, "deviant" men. In truth, there is nothing superficial or marginal about the New War that has been fought in American popular culture since the 1970s. It is a war about basics: power, sex, race, and alienation. Contrary to the Washington Post review, Rambo was no shallow muscle man but the emblem of a movement that at the very least wanted to reverse the previous twenty years of American history and take back all the symbolic territory that had been lost. The vast proliferation of warrior fantasies represented an attempt to reaffirm the national identity. But it was also a larger volcanic upheaval of archaic myths, an outcropping whose entire structural formation plunges into deep historical, cultural, and psychological territories. These territories have kept us chained to war as a way of life; they have infused individual men, national political and military leaders, and society with a deep attraction to both imaginary and real violence. This terrain must be explored, mapped, and understood if it is ever to be transformed.

Update 12/17:

This Bushmaster ad is worth 1,000 of my words above. (via Jessica Valenti)

---------------------------------------

*Jill Lepore in The New Yorker sums up the change:

In the nineteen-seventies, the N.R.A. began advancing the argument that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual’s right to carry a gun, rather than the people’s right to form armed militias to provide for the common defense. Fights over rights are effective at getting out the vote. Describing gun-safety legislation as an attack on a constitutional right gave conservatives a power at the polls that, at the time, the movement lacked. Opposing gun control was also consistent with a larger anti-regulation, libertarian, and anti-government conservative agenda. In 1975, the N.R.A. created a lobbying arm, the Institute for Legislative Action, headed by Harlon Bronson Carter, an award-winning marksman and a former chief of the U.S. Border Control. But then the N.R.A.’s leadership decided to back out of politics and move the organization’s headquarters to Colorado Springs, where a new recreational-shooting facility was to be built. Eighty members of the N.R.A.’s staff, including Carter, were ousted. In 1977, the N.R.A.’s annual meeting, usually held in Washington, was moved to Cincinnati, in protest of the city’s recent gun-control laws. Conservatives within the organization, led by Carter, staged what has come to be called the Cincinnati Revolt. The bylaws were rewritten and the old guard was pushed out. Instead of moving to Colorado, the N.R.A. stayed in D.C., where a new motto was displayed: “The Right of the People to Keep and Bear Arms Shall Not Be Infringed.”