2014: Books and Stuff

|

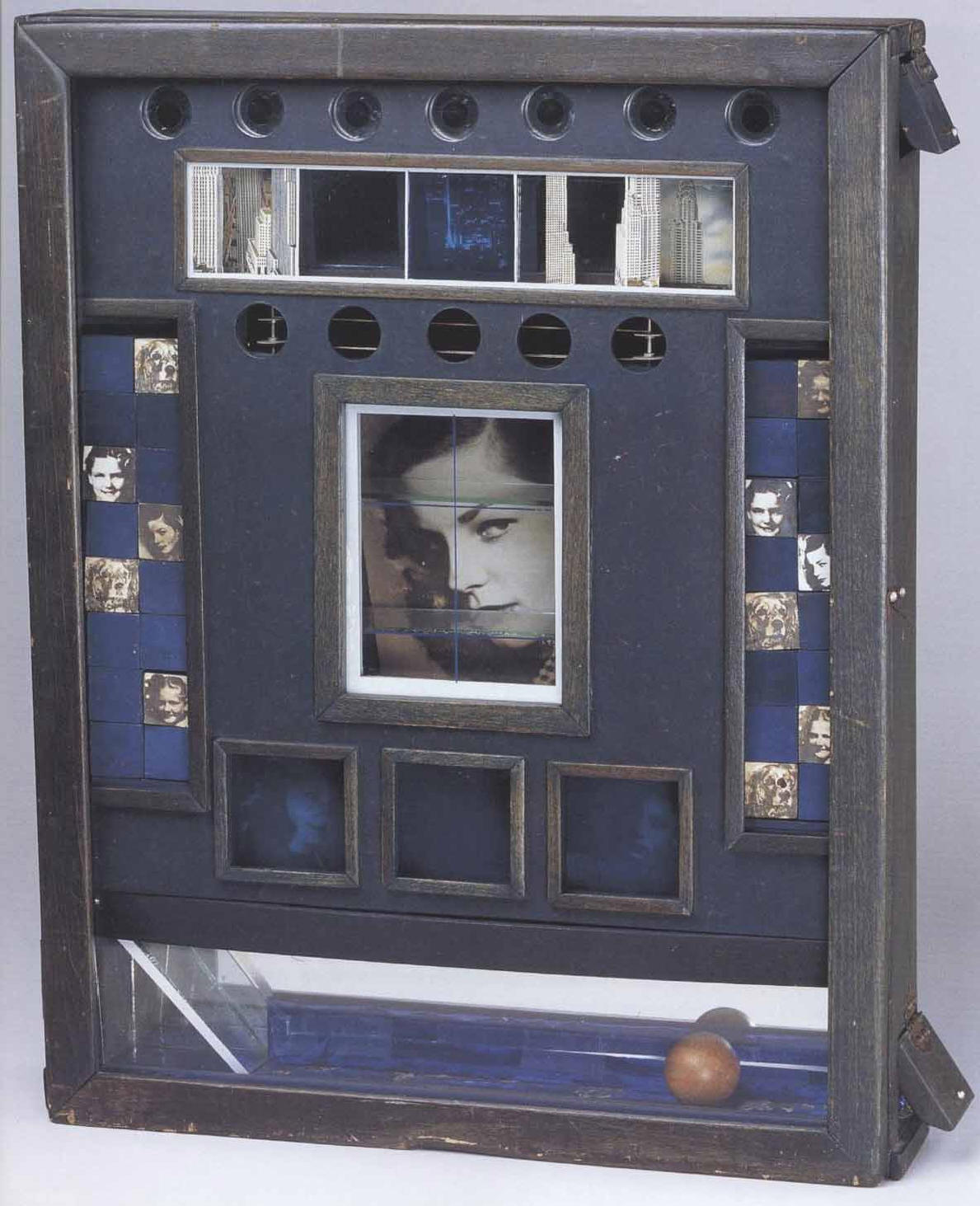

| Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall by Joseph Cornell |

I was going to write a long account of all the various things I read, saw, listened to, etc. this year, as a way of preserving some of the experience of the year for myself, and maybe offering some amusement for the occasional random reader ... but the drafts became unwieldy, and nobody, including me, wants to read all that.

(I did the math and figured out that I was assigned to read about 50 books this year by teachers in classes I took, and then I read gazillions more both for my own research and to prepare for the Ph.D. general exam, for which I needed to be ready to answer questions about any English and American lit from Beowulf till now.)

Here, then, are mere glimpses at some things that stick out for one reason or another....

Woolf.

It had been a while since I'd really dug down into Virginia Woolf's work, but a course I was taking allowed me to do that for research, and I read everything I possibly could by Woolf from the 1930s until her death in 1941. The primary effect of this work was a new appreciation for The Years, a book that does not get enough love and understanding even from devoted Woolfians.

The Dead.

I don't mean the Joyce story (much as I love it). A lot of great writers, thinkers, and people died this year: Nadine Gordimer, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Galway Kinnell, Stepan Chapman, Lucius Shepard, Stuart Hall, Jay Lake, Eugie Foster — the list goes on and on and on, and this year's list really hit me harder than any previous year's, probably because as I get older more and more people who were formative influences on me pass away. I went back and reread work by many of this year's dead. The ones I spent the most time with were Lucius Shepard and Stuart Hall. I reread Lucius's first collection, The Jaguar Hunter, and marveled again at his early mastery. I still haven't been able to bring myself to read his final Dragon Griaule book, Beautiful Blood — the end of those stories is the end of a reading adventure that dates back to my childhood.

Survivor.

My great discovery this year was that the UNH library has a copy of Octavia Butler's disavowed novel Survivor, which I wrote about here. I haven't reread the book since then, though I hope to in January, so I'll leave my original words to stand and just say: It's a fascinating, imperfect, disturbing book and I wish there were some way to get it back into print, because it is worthy of Butler's oeuvre.

Coetzee.

I've been reading J.M. Coetzee's work since my last years as an undergraduate, and writing about it for nearly as long — indeed, one of the first posts at this blog, back in October 2003, was about Coetzee. There's not another writer I've read as consistently and intensively for as long (well, aside from my writer friends. But I read them as a friend, which is somewhat different from the sort of reading I do with Coetzee). There's no other living writer with whom I feel as much aesthetic kinship, for better or worse. Many of his touchstones are my own: Kafka, Beckett, the 19th century Russians, Don Quixote. (One of these days I'll get around to writing about Quixote, which I've been reading sicne I first saw a production of Man of La Mancha as a kid and fell in love with the character. But, like Kafka and Beckett, whom I love but rarely write about, it just seems too vast and wondrous for my words.)

Anyway, Coetzee. In the first half of this year, I continued delving into In the Heart of the Country, revising a paper I was working on about that book and Afrikaner Nationalism (I had originally played around with trauma theory for it, but I really dislike applying trauma theory to fiction, and once I cut all that out the paper became markedly less awful). Then in the fall I spent good time with Foe and Elizabeth Costello, and have been hashing out a paper on the latter and its relationship to the idea of "the postcolonial novel", whatever that may be. Writing on EC is extremely difficult, partly because, like In the Heart of the Country, it is easy for interpretation to reduce it rather than open up its vast possibilities. We see this a lot in the criticism, which is mostly focused on the "Lives of Animals" chapters, and which often tries to reduce the book to the ideas its characters present rather than the way those ideas work in the fiction. (J.M. Coetzee and Ethics contains some especially egregious examples of this.)

One of the best works of criticism that I read this year, though, was Stephen Mulhall's The Wounded Animal: J.M. Coetzee and the Difficulty of Reality in Literature and Philosophy. I had known of this book for a while (it was published in 2008), but stayed away from it because it seemed to be mostly about animal rights philosophy and the "Lives of Animals" chapters. And while it is about those, it's also about much more, and offers a chapter-by-chapter exploration of Elizabeth Costello that is often rich with insights. I don't think Elizabeth Costello has much to offer that interesting or original about animal rights, but it does have a lot that is fascinating (and frustrating!) to say about realism and textuality, as Mulhall quite thrillingly shows, especially in the second half of his book. If you really want to grapple with Elizabeth Costello, this is the place to start.

Mulhall's book led me to think even more about a concept that it's fair to say obsesses me: realism in fiction. Mulhall makes a wonderful case for considering realism differently than it often is — instead of (for instance) realism vs. fantasy, he argues that it's more productive to oppose realism to idealism, and in so doing adapts an idea Toril Moi developed from Naomi Schor’s writings on George Sand: “Idealism as an aesthetics is opposed to realism; as a politics, to materialism”. It would be futile to try to explain all this here (follow the links for more), but it's an idea I want to continue to wrestle with

Milton.

I read a lot of John Milton this summer as prep for the exam. Because I was only a proper English major for one year of my life, I've never taken a general survey course after high school. (I was a Dramatic Writing major for three years undergrad, then my master's is in Cultural Studies.) Teaching high school meant I got a lot of practice in a wide variety of materials, but still: I was the teacher, so I could avoid a lot of stuff that didn't immediately interest me. Thus, I had some big gaps, areas that I'd spent twenty years ignoring. For instance, I'd never read a word of Milton. Or, rather, I'd read a couple pages of Paradise Lost ten or fifteen years ago, found it incomprehensible, and didn't ever try Milton again. But we've got a couple Milton scholars at UNH, so I figured there was a good chance Milton might be on the exam, and I spent a lot of time reading Milton. Though Milton did not end up being on the exam, I still enjoyed the work and am taking a Milton seminar in the spring (my last term of classes), so it wasn't at all a waste.

What most helped me gain an appreciation for Milton were lectures by John Rogers at Yale, available in both audio and video form from Yale Open Courses. I found many of Rogers' lectures gripping, and they opened up the poetry to me in ways nothing had before; the lectures on "Lycidas" completely won me over — they're thrilling. I also read Milton: Poet, Pamphleteer, and Patriot by Anna Beer to get a sense of Milton's life and times, as well as The English Civil Wars by Blair Worden, because while I'm relatively knowledgeable about Elizabethan/Jacobean England as well as the 18th Century, the post-Jacobean 17th Century is not an era I previously had a good grasp of. (Pretty much everything I knew about Cromwell came from Monty Python.) I also read around in Stanley Fish's Surprised By Sin and How Milton Works, Milton in Context edited by Stephen B. Dobranski, and a pile of miscellaneous journal articles (e.g. "Milton's Counterplot" by Hartman, "'Paradise Lost', the Miltonic 'Or,' and the Poetics of Incertitude" by Herman, etc.) It was a fun crash course.

Dickens.

I also spent quite a bit of time with Charles Dickens, a writer I'd read a lot in high school (a family friend was a Dickens scholar), but then ended up deciding was prolix and sentimental, so I stopped reading him for at least a decade. But, again, it seemed worth going back to Dickens and his era as preparation for the exam, and so I read Little Dorrit, which I'd never read before, and which is a delight. Yes, Dickens is prolix and sentimental, but he was also a genius, and thus he wasn't only prolix and sentimental. Indeed, passages in many of his novels are as good as English prose can get. Before reading Peter Ackroyd's magnificent Dickens biography and Michael Slater's more recent biography (focusing as much on Dickens as a writer as Dickens as a person), I hadn't appreciated how much Dickens (more specifically, his popularity) created the conditions for periodical fiction and novels in Britain in the 19th century and, following on that, the United States and other parts of the world. I read around in Dickens at Work by John Butt & Kathleen Tillotson and Becoming Dickens by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst and soon wished there were more readily accessible facsimile editions of the original periodical versions of Dickens's novels — I have one for Nicholas Nickleby, and there are some online versions, but the ideal would be to reprint the separate little paperbacks (which is apparently what the Discovering Dickens reading project did in the early 2000s, but as far as I can tell the actual books are nearly as rare as the originals, as are the Easton Press limited serial-facsimile editions of Pickwick and Copperfield).

The Case for Reparations.

I've respected and learned a lot from Ta-Nehisi Coates's work over the years, but this piece is extraordinary. It should be retitled, "This Is White Supremacy". If you care about race or U.S. history or humanity in general, read it. I expect historians 50 years from now will look back on it as one of the important documents of our time.

No Future.

Lee Edelman's No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive is a book I read too quickly to really absorb, but it was also one of the most mindbending books I read all year. (It directly influenced my Black Static story "Patrimony".) The book positions an idea of the queer in opposition to the idea of futurity embodied by procreation, specifically in the figure of the child and its innocence, purity, etc. In some ways, Edelman's book is a nice companion to Thomas Ligotti's work, and I read it only a couple months before I read the Ligotti interview collection Born to Fear. Neither is especially cheery, but I do find them somehow strangely ... clarifying.

Timothy Morton does a good job of thinking about doom in his new book Hyperobjects, which I also read too quickly to be able to give much analysis to, but I'm generally sympathetic to Morton's approach from his previous books Ecology without Nature and The Ecological Thought. At the same time, it's often seemed to me in the past, perhaps because I'm really not a philosopher, that Morton skipped around ideas without really developing them, and the concepts in Hyperobjects seemed to me to allow him to actually say more than in the past, which might just be a result of my getting used to his way of writing.

The Southern Reach.

Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach Trilogy is extraordinary, but I read it as late-stage drafts while I was in the midst of all I described above, and the texts did change some (especially Acceptance) after the versions I read ... so I really can't claim to have "read" these in the way one normally expects the word "read" to mean. I'm hoping to read the finished versions at a more leisurely pace, with more of my brain to devote to them, in the coming weeks, because they haunted me before, even as I was frazzled with other work and reading on the go in snips and snatches. Maybe that was the best way to read them through the first time, so that the books remain not as a narrative in my mind, but as flashpan sparks of images, words, moments. Certainly, one of the great thrills for me this year was watching as the books became the most popular things Jeff has ever written. There are very few satisfactions to compare to the satisfaction of a close friend or family member finding success beyond what they ever expected.

Lorde. Glück.

I had two poetic companions this year: Audre Lorde's Collected Poems and Louise Glück's Poems: 1962-2012. Both books are vast, and so they allow the reader to skim around, to skip and bounce off of their extraordinary words, phrases, lines. I think of both books as sharp — smart, yes, but cutting, too: they will scratch and draw blood. Whenever I despaired for trut

h, I went to one or both of these books. 2014 was a scarring year in some ways, and the poems of Audre Lorde and Louise Glück helped make those scars, if not less painful, more bearable, more comprehensible.

Basement Tapes.

It took more than 45 years, but we now have Bob Dylan's fabled Basement Tapes in an official release, beautifully restored to their original inelegance. Sasha Frere-Jones is right in his review to say that the complete set (as opposed to the selected highlights) is likely for obsessives only, but the highlights edition is missing some good tracks, and the complete edition allows a truly remarkable listening experience for anybody interested in Dylan's creative process, or creative processes in general: we get to listen to a genius mess around, try things out, fail and flail, stumble upon wonder. Nobody involved with these recordings originally thought that the general public would ever hear them. These were not recordings made for us. But now we get to be voyeurs and listen to extraordinary musicians playing for an audience only of themselves.

An extraordinary, heartwrenching, infuriating documentary about the firebombing of MOVE in Philadelphia in 1985. In his September 2013 review of the film, Stuart Klawans wrote: "People who think that America is entering a postracial era will view Let the Fire Burn as a period piece. People who think that such mutual incomprehension is still commonplace in our society, and still concludes too often with a black corpse on the street, will watch the movie as if it is today’s news, filmed thirty years ago."

In the year of Ferguson and "Hands Up! Don't Shoot!"; the year of Eric Garner and "I Can't Breathe!"; the year of Tamir Rice; the year of #BlackLivesMatter — in that year, our year 2014, this documentary is all the more necessary to our national conversation. If there's one movie I saw this year that I could make everybody I know see, it would be this.

Texas Chainsaw Massacre: 40th Anniversary.

Texas Chainsaw Massacre, one of the greatest of American artworks, was released 40 years ago, and this year a restored print received a limited theatrical run and then release as an excellent Blu-ray/DVD package. TCM is not just a horror film (for some people, the most horrifying of all), but also an extraordinary expression of the apocalyptic tendency in American narrative art, a tendency that dates back centuries. In comparing TCM to The Omen, Robin Wood succinctly showed its radical difference from mainstream, studio horror movies of the '70s, and the difference remains potent even today, when the low-budget aesthetic has become so common to horror that it no longer holds much punch as an aesthetic. Because TCM so effectively evokes many of the basic horrors at the heart of American mythology, it remains both a potent, even overwhelming, experience and a remarkable critique of so much that we in the U.S. are conditioned to hold dear.

Twin Peaks: The Entire Mystery.

I watched Twin Peaks when it first aired on CBS in 1990 and 1991, and it rearranged my brain and permanently affected my aesthetic sense. (And made me a die-hard David Lynch fan.) I got the DVDs of the show for Christmas the year my father died, and watched them all in those first weeks when I was trying to figure out how I'd have to rearrange my life, since I'd suddenly become heir to a gun shop and a house. They were the perfect accompaniment to those surreal days. And now, with the big Blu-ray box called The Entire Mystery, we have the episodes beautifully presented, with more extra features than I've yet had time to watch.

Hannibal.

I don't watch much network TV — mostly, I watch crime shows on Netflix while eating dinner. (I don't know why crime and mystery stories are the only ones I really enjoy as serial work, but that's how it is.) Nothing I've seen since The Wire has affected me as deeply as Hannibal, and no TV show I've seen since Twin Peaks has seemed as aesthetically vital. The best writing I've seen about Hannibal has come from Matt Zoller Seitz, so I'll just direct you to him to see why it's such an extraordinary show: on Season 1; on Season 2; as 2014's best drama on TV; as the best show of 2014.

I wrote about the second season (of the second iteration) of the Swedish Wallander back in 2013, and then this year got to see the third season's six episodes, which end with Wallander's retirement. (The season begins with the plot of Henning Mankell's final Wallander novel, The Troubled Man, but Wallander's own conclusion is built up through all the episodes.) The third season is tonally quite different from the second, and most of the cast is different. Linda, Wallander's daughter, is back, having been dropped in the second season after actress Johanna Sällström's death, and Charlotta Jonsson is very good in the role. The season is very much about Wallander's decline into Alzheimer's, and as such it's one of the most powerful fictional presentations of Alzheimer's that I know, even if the mystery plots are not as compelling as before. (I don't think they should be. The third season is about Wallander the man, and the plots are there to support our understanding of his crisis.) The last episode is overwhelmingly powerful for anyone who, like me, had watched all of the previous episodes. Krister Henriksson deserved every award in the world for his work in this season. I was also pleased that the writers found a way to avoid a bleak ending. It's sad in the way many things in life are sad, but it's emotionally nuanced and complex, too — even, at the end, sweet, which seems entirely appropriate for this show.

Snowpiercer.

I wrote a lot about Snowpiercer when it came out, as did plenty of other people, as it's the sort of movie that seemed to make people want to write essays, comments, screeds. It was one of the more divisive movies of the year, one of those movies people seemed incapable of feeling indifferent toward (either you loved it or hated it), and one I ended up feeling very protective toward, for reasons that remain somewhat mysterious to me. One of the things it seemed to do was separate people whose evaluative emphasis is on narrative coherence, plausibility, etc. — at an extreme, Hitchcock's dreaded plausibles — from people whose emphasis is more toward the cinematic. The basic premise of Snowpiercer is, in many ways, so ridiculous as to be beyond implausible. Even more infuriatingly for some folks, it teases us toward a reductively allegorical interpretation. Some viewers could not see value in the film beyond that. When trying to think through people's negative responses to the film, I think what bothered me so much is what bothers you whenever you love something and other people really, really don't: there's no way to have a productive conversation. There's no bridging that gap. If you hated Snowpiercer, there's pretty much nothing I can say that will make you agree with me; nor is there anything you can say that will make me see the movie the way you do. In fact, in any meaningful way, you and I see utterly different movies. Mild disagreements and different interpretations can be discussed and such positions can be overcome, but some things affect us too deeply — they exist at a level far beyond the rational.

For me, Snowpiercer deserves the label total cinema because it brings together so many different elements (acting, cinematography, production design, sound design, etc.) that create a unified effect that is only cinematic. Not literary, not craft, not music, but all of those (and more!) into one. Some elements inevitably get more emphasis than others, but it is the play of elements, their interaction, that defines the cinematic. It was that force that I responded to so fully, and why the film worked for me so well, and why I had to create a video essay to try to show it, because limiting myself only to words can't convey even half of what the film does to me.

Mr. Turner.

I responded even more viscerally to Mr. Turner than to Snowpiercer, and I also expect Mr. Turner will be divisive, though fewer people will likely see it, and it's not as explicitly open to political readings, so there probably won't be many essays about its political implications. But again, the filmmakers' aesthetic and narrative choices will alienate many viewers while enrapturing those of us who, for whatever reason, are open to them. For me, it's the best 2014 movie I've yet seen.

Jamie Marks Is Dead.

A movie based on a book that I read in manuscript from one of my favorite writers and people is going to have a lot to prove, and Jamie Marks Is Dead, based on Christopher Barzak's first novel, One for Sorrow, proves a lot. I enjoyed it far more than I expected to, and though I understand why it struggled a bit to find an audience (not an easy movie to reduce to a tagline or a particular audience type), I still wish it had become a big breakout hit, or at least made it to more critics' best-of-the-year lists. It's a movie that deserves to be seen, a movie made with real skill and sensitivity, a model of how a truly faithful adaptation does not need to just reproduce a bunch of scenes from the book.

The Raid 2.

I enjoyed The Raid, but The Raid 2 tops it in every way. Indeed, it's one of the best action movies I've ever seen. It's excessive in every way — it's so bloody it sometimes seems like a slasher movie — but it's creatively excessive, which is key. It's not an animated-with-CGI blockbuster, but a brilliantly choreographed dance of destruction. In its own way, it hearkens back not just to the great martial arts movies of the past, but to Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd.

Only Lovers Left Alive.

I've really come to like Jim Jarmusch's films from Dead Man on (his earlier work just doesn't quite capture my interest), and Only Lovers Left Alive is easily my favorite of them. It's the best vampire movie since Let the Right One In, but it's far more (or other) than a vampire movie. It's a masterpiece of suggestion and mood, of hint and tease, and it's a joy just to hang around in its crepuscular world.