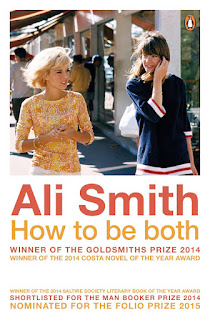

Let's Do the Twist: How to Be Both by Ali Smith

I've been meaning to catch up with Ali Smith's novels for a while now, having previously only read Hotel World, and so when it came time this summer to formulate reading lists for my PhD qualifying exams, I stuck How to Be Both on the fiction section for the Queer Studies list. (This also explains why I was writing about The Invaders recently...)

How to Be Both turns out to be even more appropriate to my Queer Studies studies than I'd suspected from reading reviews, and it shows how the structures of fiction can be at least as provocative and productive as certain types of social and political philosophy. How to Be Both is generally a very readable, enjoyable book — in some ways deceptively so. In that, it reminds me of Kurt Vonnegut's best books, which manage to play with some complex ideas in light, entertaining ways. (Smith's novel would make a marvelous companion to Vonnegut's Mother Night in a course on the novel and history...) How to Be Both does quite a lot to challenge ideas of time, history, language, and various normativities, but it does so without collapsing into vagueness, abstraction, or pedantry; quite the opposite. It bears its own paradoxes far better than many works of vaunted critical theory, which end up, at their worst, sputtering out in abstraction and self-parody, like a Mad Libs version of an Oscar Wilde epigram.

Over the last ten years or so, there's been discussion among Queer Studies folks of queer temporality and historicism — the effect of contemporary vocabulary ("queer", "gay", "lesbian", "homosexual", "transgender") on a past that used different words and ideas; the relationship of past behaviors and ideas to present ones; the political power of the past for the present; the similarity or difference of past worlds to our own; how we express such similarity/difference; the experience of history as a queer person; etc. (Of course, the roots of this conversation go way back, but there have been particular spins on it recently.)

In 2013, Valerie Traub published a significant response to some of the more prominent discussions of these ideas, particularly among Renaissance scholars: "The New Unhistoricism in Queer Studies" (to which there was more response later), which is a relatively accessible entry point to some strands of discussion. Here's a bit of Traub:

Rather than practice “queer theory as that which challenges all categorization” ... there remain ample reasons to practice a queer historicism dedicated to showing how categories, however mythic, phantasmic, and incoherent, came to be. To understand the arbitrary nature of coincidence and convergence, of sequence and consequence, and to follow them through to the entirely contingent outcomes to which they contributed: this is not a historicism that creates categories of identity or presumes their inevitability; it is one that seeks to explain such categories’ constitutive, pervasive, and persistent force. Resisting unwarranted teleologies while accounting for resonances and change will bring us closer to achieving the dificult and delicate balance of apprehending historical sameness and difference, continuism and alterity, that the past, as past, presents to us. The more we honor this balance, the more complex and circumspect will be our comprehension of the relative incoherence and relative power of past and present conceptual categories, as well as of the dynamic relations among subjectivity, sexuality, and historiography.Ali Smith's novel explores and even embodies this discussion, and does so in many ways that both the unhistoricists and the historicists seek to valorize. And it's more fun to read than their essays.

First, there is the form: The book tells two different stories, with one being the first half of the text and the other the second half. Which is which depends on the particular copy of the book you get — half of them begin with the story of the painter Francescho [or Francesco] del Cossa, the other half begin with the story of George (short for Georgia), a teenager in contemporary England whose mother has recently died. (The e-book apparently allows you to choose which order you want.) The copy I have out from the library begins with George, which seems to me to be the friendliest, easiest entry point, because the Francescho section begins much more lyrically, and it takes pages to get your bearings. It all makes sense once you know the situation and various references, but you don't really get to know those until later, so for a while the Francescho section just seems like rambling nonsense. (It is rambling; it isn't nonsense.) The opening of the George section is, on the other hand, quite marvelous and engaging. I zoomed through the whole 186 pages of that part quickly and with pleasure. It took longer for me to get interested in the Francescho section, but in some ways that one proves to be the richer and more satisfying, which is another reason I'm pleased to have read it as the second half rather than the first.

Some reviewers have speculated about the different ways readers could interpret the texts based on which they read first, but I'm not sure the difference is so much in interpretation as it is in expectation and in the reading experience itself. The pacing of the two sections is different, and so the book will feel different if you read one first rather than the other. There are connections you'll make differently based on which you read first, but I'm not sure how much that really matters except in the moment of reading, since once you turn the last page, you've got all the information as a set in your mind. For instance, the Francescho section gives us the story behind some paintings that are speculated about in the George section, and so reading the George section second would cause you to compare the speculations to the story you know from the Francescho section. I didn't feel it was a significant difference to encounter those stories second, since they are already presented in the George section as speculation, so I didn't read them as anything except the guesses and imaginings of the characters, which is what you still read them as even when you know other stories behind the paintings.

One thing uniting the academic historicists and unhistoricists is a sharp suspicion, and sometimes outright rejection, of teleology. (Traub: "Since around 2005 a specter has haunted the field in which I work: the specter of teleology. ... A teleological perspective views the present as a necessary outcome of the past—the point toward which all prior events were trending.") This is a problem for anybody writing a narrative, because narrative is purposeful, and most narratives are aimed toward their conclusions. For a long time, the whole idea of a well-wrought story has been one where, in fact, the conclusion is indeed "the point toward which all prior events were trending." A carefully constructed plot is, pretty much by definition, teleological.

Various Modernist writers tried to escape the teleological properties of narrative through disjunction, juxtaposition, impressionism, and surrealism, but teleology proved hard to escape except in the most abstract writing, or in works where it literally doesn't matter what order you read things in (e.g. Hopscotch or The Unfortunates) — although even then, in the assembling of meaning, the reader is still likely to impose a teleology at the end, even if the author has used a form that itself makes no such imposition. We want, as readers, to say that where we ended up is a direct result of where we began. It's a pretty unsatisfying story if the conclusion isn't in relationship to what came before, and preferably a relationship of causality and purpose. Even if the narrative itself works hard to escape teleology, there's still the matter of the writer's purpose in constructing that narrative.

In the early 20th century, a lot of the more avant-garde writers sought to create works that did not promote a particular moral idea or lesson (one hallmark of teleology), but more often than not this led to a new sort of purposefulness embedded in the text (if not a chronological text, then a chronological reading experience infused with a sense of purpose). (For more on this, see "Modernism and the Emancipation of Literature from Morality: Teleology and Vocation in Joyce, Ford, and Proust" by David Sidorsky. It's from 1983, but I haven't seen anything more recent that does a better job of really digging in to the question of Modernist narrative and teleology.) How to Be Both doesn't escape teleology, but it does play around with it, creating anti-teleological effects that work beautifully because they're embedded like booby traps and surprise parties in the narrative. We get the anti-teleological effects and we get the inescapable, purposeful, and even linear, movement inherent to storytelling.

Additionally, How to Be Both manages to question identity categories without pretending that identity is an unimportant concept. Past and present become interestingly different and similar, readable and prone to misreadings. In that, it's perhaps squaring some of the circles proposed by queer theory in the last ten or fifteen years.

Here's a key passage from one of the essays that Traub responds to most fully, "Queering History" by Jonathan Goldberg and Madhavi Menon:

...the challenge for queer Renaissance studies today is twofold: one, to resist mapping sexual difference onto chronological difference such that the difference between past and present becomes also the difference between sexual regimes; and two, to challenge the notion of a determinate and knowable identity, past and present. Even if the model of past alterity were to be replaced with a model of past similarity—sodomy is similar to rather than different from current regimes of homosexuality—that similarity should lead not to identity but rather to the non-self-identical nonpresent. To queer the Renaissance would thus mean not only looking for alternative sexualities in the past but also challenging the methodological orthodoxy by which past and present are constrained and straitened; it would mean resisting the strictures of knowability itself, whether those consist of an insistence on teleological sequence or textual transparency. This version of homohistory thus does not necessarily refer to homosexuality at all. Rather, it suggests the impossibility of the final difference between, say, sodomy and homosexuality, even as it gestures toward the impossibility of final definition that both concepts share. Paying attention to the question of sexuality as a question involves violating the notion that history is the discourse of answers, a discourse whose commitment to determinate signification, Jacques Rancière has argued, provides false closure, blocking access to the multiplicity of the past and to the possibilities of different futures.Gesturing toward the impossibility of final definition is one way to express some of what How to Be Both is up to. The past in this novel is full of multiplicity and there's very little closure of any sort, whether "false closure" or not — even death is not closure, because a ghostly consciousness survives to narrate.

I haven't done a search of the text, but I don't think any words for sexual identity appear in it (if they do, they don't do so in a memorable way, at least for me). It's a small item, but an important one: what we make of the relationships in either story is up to us, and so the characters' identities remain more conceptually open in our minds than they would were they even to be labelled as queer — unless, of course, we impose our own labels on them, which is a move the text itself playfully parodies in the Francescho section, where Francescho's gender bending is accepted and explained by saying "he's a painter", with the word painter easily standing in for whatever deviation from social norms is discussed.

Francescho, for instance, is morphologically female, but functions socially as a man by wearing men's clothes and working in a male profession. How to Be Both is one of the more interesting accounts of historical cross dressing that I've read because it is generally so blasé about that cross dressing. (And by "historical", I don't mean "historically accurate" — hardly anything is known of the actual Francescho del Cossa, and there is no indication that he was identified as a woman at birth. More on this in a moment.) Francescho becomes Francescho after her mother's death, when her father proposes that she could wear her brothers' clothes and thus go to school and eventually apprentice to an artist. She shows great talent, but as a woman would have no possibility of training or opportunity to get art commissions. The solution to that problem is to stop being a woman. This has little to do with the body and everything to do with clothing and presentation. This is clearest at the moment where Francescho's best friend, Barto, is told that Francescho is a woman. His surprise and feeling of betrayal is a surprise to Francescho (who has the annoying habit of using "cause" for "because"):

Cause there'd been many times when Barto'd seen me naked or near-naked, by ourselves swimming, say, or with other boys and young men too and the general acceptance of my painter self had always meant I'd been let to be exactly that — myself — no matter that in 1 difference I was not the same : it was as simple as agreement, as understood and accepted and as pointless to mention as the fact that we all breathed the same air : but there are certain things that, said out loud, will change the hues of a picture like a too-bright sunlight continually hitting it will : this is natural and inevitable and nothing can be done about it...Here, the speaking of difference creates the difference. Barto only becomes angry with Francescho for "lying" about gender when he is told by someone else that Francesco has been "false":

Is it true? he said. You've been false? All these years?This is not a moment in which identity is obliterated or even especially fluid, and yet it's also far more complex than one in which a contemporary category is imposed on the past. Identity exists in various forms: "my painter self" is not a false self, but a modified, incomplete self (incomplete in that it is not the whole self, which is probably unutterable if not inconceivable). A good friend, such as Barto here, is going to know a person in a way that moves beyond categories, but also in a way that is constrained by circumstances, experiences, and assumptions — just as our own knowledge of our self is constrained by circumstances, experiences, and assumptions. In the brief bit of dialogue above, knowability is both asserted and shown to be inevitably incomplete. What is "natural and inevitable and nothing can be done about it" is not identity or sexuality or self or other, but rather the effect of what is spoken about identity, sexuality, self, and other. Words create worlds.

I have never not been true, I said.

Me not knowing, he said. You not you.

You've known me all along, I said. I've never not been me.

You lied, he said.

Never, I said. And I have never hidden anything from you.

The George section approaches all this in an entirely different way. It's set around 2014 in Cambridge, and it tells a variety of stories, including the story of George's mourning for her mother, who was an economist, writer, and internet provocateur. George's memories of her mother are memories of conversations that often involves words and meanings. (George is an aspiring grammar pedant, which both riles and amuses her mother.) It also tells the story of George's awakening desire for her friend Helena (whose friends call her H), a precocious, lively young woman who opens other worlds to George.

Again and again throughout this section, words and their meanings flow and shift playfully. George is a nickname for Georgia, and there's a wonderful perceptual effect to reading a story in which a rather male name is attached to a rather female character — by the time she's called "Georgia" by someone, it seems awfully formal and in many ways just plain wrong.

Time and perception are slippery throughout the novel, and they are slippery because of the effect of time on living. The George section begins:

Consider this moral conundrum for a moment, George's mother says to George who's sitting in the passenger seat.Look at all that! All the doubling, all the slippage, all the revising of perceptions! We start reading with, probably, the reasonable assumption that George is a boy, and thus the "You're an artist, her mother says" comes as a surprise and makes us, perhaps, reread the first few lines, or at least reconfigure the image (however tentative) of George in our mind. (The exact same thing happens, though for different reasons and different assumptions, with Francescho's ghost, who is the narrator in the other section. The ghost sees George in a museum and, for reasons of changes in fashion, etc., assumes it's a boy. "This boy is a girl," Francescho writes at the beginning of the second chapter of the section.) Then there is the struggle with tense: present goes to past, and the final paragraph I've quoted adds (vertiginously) more precision, though the effect on the tenses is even more twisty: the conversation is (present tense) happening in the past. Twisty, too, is the effect of imagination, which, as a companion to words, creates worlds: George as artist, George as driver.

Not says. Said.

George's mother is dead.

What moral conundrum? George says.

The passenger seat in the hire car is strange, being on the side the driver's seat is on at home. This must be a bit like driving is, except without the actual, you know, driving.

Okay. You're an artist, her mother says.

Am I? George says. Since when? And is that a moral conundrum?

Ha ha, her mother says. Humour me. Imagine it. You're an artist.

This conversation is happening last May, when George's mother is still alive, obviously. She's been dead since September. Now it's January, to be more precise it's just past midnight on New Year's Eve, which means it has just become the year after the year in which George's mother died.

Twisty: It's a recurring idea in the book, most heavily but not exclusively in the George section. There's the song and the dance of The Twist. There's also DNA: George's home of Cambridge is also home to the Cavendish Laboratory (The book notes that the twisty structure of DNA was not just discovered by the famous men, but also by Rosalind Franklin). Ideas, identities, worlds twist and interrelate.

Here we have, then, not teleology so much as interrelationship. Not linear progress, but temporal parallels. Not an arrow from the past pointed at the future, but a dance of partners. Perceived separately, they are one thing. Perceived together they are one thing else. Separate, yes, but also together. Different, yes, but also a same. Both.

Late in the Francescho section, Barto offers two cups of water to Francescho to help overcome sadness and anxiety: one cup, he says, holds water of forgetting, one cup holds water of remembering. They come from the same jug, which perplexes Francescho:

So it's the cups of forgetting and remembering and has nothing to do with the water?How to be both is what we need to learn, and what we need to learn to perceive. There's a certain monadism to it: everything is, ultimately, one ... and yet to survive, to make sense of the world, to function from day to day, to speak and dream and desire ... we have to have separates. The water is one, and it is not one.

No, it's the water, he said. You have to drink the water.

How can the same water be both? I said.

It's a good question, he said. The kind of thing I'd expect you to ask. So. Ready? So first you drink—.

It would mean that forgetting and remembering are really both the same thing, I said.

Don't split hairs with me, he said.

Don't split hairs, though. Intention matters, reception matters, perception matters. Labels matter: This is the water of forgetting because we both agree it is the water of forgetting, not because of its origin or its biological properties. Barto doesn't pay close attention to which cup he said was which, and when he and Francescho can't agree on which was poured as the water of forgetting and which as the water of remembering, they have to start over. Which is which is a social fact, and that means they have to agree on which is which for the water to do what it is supposed to do, because what it is supposed to do depends on their mutual perception. Their perceptions must dance together, must twist and helix.

It isn't all just fun and games. Perceptions create realities, and not always good ones. Francescho is paid less than male painters by a Duke because the Duke likes male painters best and has found out that Francescho is physically female. He doesn't like Francescho less as a painter, but instead values him less as a him. (This whole incident is then perceived differently by George and her mother — it is the moral conundrum of the opening, but it is not the moral conundrum it was in Francescho's time because George and her mother do not know that Francescho was perceived by the Duke as a woman painter, and thus less captivating to his desires. The moral conundrum of payment, self-worth, ego, and skill is, though, one well worth thinking about and talking through, even if it is not the one that Francescho was thinking about and talking through. It is both.)

This brings us then to the question of what we do about the past. What can be known, and what do we impose? Is Smith wrong about the real Francescho del Cossa? Yes, no, neither, both. Anything said about del Cossa beyond the very few known facts is wrong, or at least fictional, a matter of speculation. To speak is to create a story, to impose a viewpoint on the past, no matter how objective you try to be, because to speak the past is to narrate the past, to move from isolated facts to connected history. Speculation may not help us know the past, because the past may lie beyond knowability, but speculation can help us know ourselves as we imagine we know the past, and there is value in that.

Knowability isn't only a matter of the past, as How to Be Both shows. We perhaps assume we know the present and the people close to us, but strangeness (even queerness) is everywhere. This is what I take to be the purpose of the mysterious character of Lisa Goliard, whom George tries to fix an identity on: Was she her mother's friend? A fan? A lover? The book never answers these questions definitivey. Lisa Goliard remains a free-floating signifier from George's mother's life. She can be seen, even surveilled, but not known. Her story is outside George's story, no matter how much George wants to twist it into her own. She is what can't be known, what can't be pinned down, even in the present. History knows more of Francescho than George is able to know of Lisa Goliard, a living woman whom she's able to spy on. But seeing — perceiving — is not the same as knowing. The two sections of the book have icons, and the icon for the George section is a surveillance camera. The icon for the Francescho section is del Cossa's own drawing of eyes on flower petals. Sight via technology, site via nature, art, and whimsy. Both forms of sight are incomplete mediations.

Perspective, too, matters: "It's as if," George thinks after looking a long time at a painting, "just passing from one side of the saint to the other will result if you go one way in wholeness and if you go the other in brokenness." She adds: "Both states are beautiful." It's a theme throughout the book, expressed again and again: doubleness, perception, beauty. It's the twistiness encoded in DNA and in art. The book itself is like a fresco that has been painted over or a canvas that has accumulated multiple pictures. Francescho learns this lesson early when watching a master painter work:

and from looking at whose works I learnedProse struggles to tell a story more than one way at once, since we read linearly. But that idea of a story underneath another story, rising up through the skin — that idea is woven into this book's form, a book that suggests the idea is also woven into the form of our selves, if we take the time to look. Art and life do not need to be separate:

the open mouths of horses,

the rise of light in a landscape,

the serious nature of lightness,

and how to tell a story, but tell it more than one way at once, and tell another underneath it up-rising through the skin of it

I like very much a foot, say, or a hand, coming over the edge and over the frame into the world beyond the picture, cause a picture is a real thing in the world and this shift is a marker of this reality : and I like a figure to shift into that realm between the picture and the world just like I like a body really to be present under painted clothes where something, a breast, a chest, an elbow, a knee, presses up from beneath and brings life to a fabric : I like an angel's knee particularly, cause holy things are worldly too and it's not a blasphemy to think so, just a further understanding of the realness of holy things.The ideas, though, continue to twist, because to Francescho, these are just "mere mundane pleasures", and what really matters is (of course) a matter of "2 opposing things at once":

The one is, it lets the world be seen and understood.And there we have it. How to Be Both is, in fact, both.

The other is, it unchains the eyes and the lives of those who see it and gives them a moment of freedom, from its world and from their world both.