Shirley Jackson at 100

Today is Shirley Jackson's 100th birthday, and as I think about her marvelous body of writing, I can't help also thinking of the changes in her reputation over the last few decades, or, rather, my perception of the changes in her reputation. For me, she was always a model and a master, but there was a time when that opinion felt lonely, indeed.

I discovered her as so many people discover her: by reading "The Lottery" in school. (Middle school or early high school, I don't remember which.) I loved the story, of course, but it wasn't until I got David Hartwell's extraordinary anthology The Dark Descent for Christmas one year that I really paid attention to Jackson's name, because the book includes the stories "The Summer People" and "The Beautiful Stranger", both of which I read again and again. Around the same time, I read Richard Lupoff's anthology What If? and thus encountered what would become one of my favorite short stories by anyone: "One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts". After that, I sought out Jackson's work wherever I could find it.

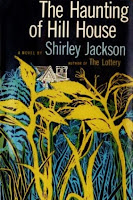

But it was not easy to find Jackson's books. This was the late 1980s, early 1990s. When I first started looking, nothing seemed to be in print. I got an omnibus edition of her most famous books, The Haunting of Hill House, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and The Lottery and other Stories (which ISFDB says was published in 1991; I expect I got it a year or two later). From one of the local libraries (which had hardly anything by Jackson, including the local college library) I was able to read The Magic of Shirley Jackson, which included some of her short stories, The Bird's Nest, and her two collections of humorous family stories (which I didn't pay much attention to). At some point, I got a battered and water-damaged old paperback of The Bird's Nest. I read the library's copy of Judy Oppenheimer's biography.

And that was it. I tried for years to find copies of novels I'd only read descriptions of, particularly Hangsaman and The Sundial, but they seemed not to exist except as expensive listings in used book catalogues.

Jackson was seen as a minor writer. While bookstore shelves filled to bursting with the endless emissions of Updike, Mailer, and their ilk, Jackson was perceived, at least by the literary mainstream, as the weird lady who wrote that story about the village where people stone each other to death ... and that horror novel that they made into a really creepy movie ... and wasn't there something about a castle?

By the end of the 1990s, though, a change was afoot. A new generation of American writers who had read "The Lottery" in school and thought not "Ewww! Weird!" but "Hooray! Weird!" began publishing their own work. (Think Kelly Link and Jonathan Lethem, just to choose two of the most currently prominent, and two who explicitly cite Jackson as a literary hero.) The moment when things felt like they were changing — that is to say, the moment I really noticed a change in Jackson's status — was in early 1997 with the publication of Just an Ordinary Day, a collection of previously uncollected and unpublished stories. Jonathan Lethem's review of the book for Salon gives a snapshot of just how much about Jackson had to be introduced to readers back then.

In the summer of 1999, a big-budget remake of The Haunting was released in theatres, bringing the novel back to prominence. In July of 2000, a Modern Library hardcover edition of The Lottery was released. (Around this time, too, I remember seeing the Penguin edition of We Have Always Lived in the Castle in stores with the cover that ISFDB says is of the 1984 version. I don't know if it was technically out of print between 1984 and the late 1990s/early 2000s, but it was definitely scarce.) In 2008, the first Shirley Jackson Awards were presented. In 2010, the Library of America canonized Jackson with an omnibus collection of The Lottery, The Haunting of Hill House, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and some miscellaneous stories and sketches, all selected by Joyce Carol Oates. By early 2014, thanks to Penguin Classics, all of Jackson's novels were in print for the first time in about fifty years. In the summer of 2015, a new collection of uncollected/unpublished works was released, Let Me Tell You. This year, Ruth Franklin's excellent biography of Jackson was published to acclaim, and has already done a lot for Jackson's reputation. For me, it is the most significant biography of an American writer since Julie Phillips's biography of James Tiptree, Jr., and the two books have a lot in common, particularly in how they illuminate the eras during which their writers lived and wrote. (A course that used both biographies alongside the writers' works would present a powerful, disturbing picture of mid-20th-century America.)

The rescue of Shirley Jackson from a reputation as a minor writer is one that reminds me of the rescue of Virginia Woolf. It's difficult to imagine now, when even Woolf's most marginal writings are in print and she's among the most heavily studied writers in the English language, but before the intervention of feminist scholars in the 1970s, Woolf was considered a minor modernist and most of her books were out of print in the U.S. (Hugh Kenner, who could never forgive Woolf for disliking Ulysses, sneered in the pages of a 1984 issue of the Chicago Review that Woolf is "not part of International Modernism; she is an English novelist of manners, writing village gossip from a village called Bloomsbury for her English readers..." Kenner's response was in many ways a backlash against the feminists' success in bringing Woolf to more prominence. I expect a backlash against Jackson at any moment.) We might also make a comparison to the reputation of Philip K. Dick, whose books I remember having to scrounge in used bookstores to find because hardly any were in print. Certainly, Jackson hasn't (yet) attained the huge posthumous success of PKD, but it seems to me that her works are similarly of their time and very much ahead of their time — and are so in a way that the work of writers who were more famous and respected when Jackson and PKD were alive and after (Updike, Mailer, etc.) are not. The props and scenery of her books and stories evoke their era, but the works' structures and obsessions are like piranhas swimming undercurrents right into our contemporary psyches.

Jackson was a great writer on many levels: her best prose seems effortless but is subtle and stunningly acute, her best stories are unpredictable and unsettling in ways that approach the sublime, and in even her lesser works a unique perspective on life (and death) pervades each page. Her most famous writings really are her best, but her less balanced, less perfect books and stories also deserve to be read and studied. Though The Bird's Nest, Hangsaman, and The Sundial are lesser achievements than Hill House and Castle (as well as quite a few of the stories), they are very much Shirley Jackson novels, and second-tier Jackson is still an order of magnitude more affecting and accomplished than most of what her American contemporaries wrote.

Let's celebrate Shirley Jackson at 100, then, and celebrate the fact that we finally live in a world where her literary accomplishment can be appreciated.