Elements of Style for the Age of Blight

Introductory

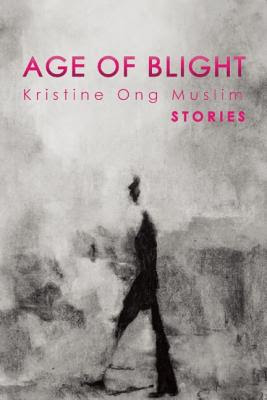

As the world burns away in political crises and ecological catastrophe, writers strain against meaninglessness, against the sense that their work is nothing more than a few grains of confectionary sugar tossed to a howling wind. What forms might fit our time, what stories might we tell against a future of no-one left to listen to stories?

No other label for where we are and where we’re going as a world seems quite so accurate as the one Kristine Ong Muslim has used for her recent collection of stories, The Age of Blight. It is a book of glimpses, shards, and lost myths; it works like a nightmare recollected during the day before you know the nightmare will return and sleep cannot be kept at bay indefinitely.

The Age of Blight and a thousand books like it will not forestall our own Age of Blight, but Muslim offers strategies for storytelling as the blasted era blightens. Her techniques for writing fiction are ones that make demands on the reader, but they're not the demands made by, for instance, a doorstopper novel flooded by streams of consciousness.

Elementary Rules of Usage

For all the enormity of its subject matter, Muslim’s book is tiny. It gathers 16 short stories in 103 pages (some of which are blank). The effect of reading it is similar to what it might be like to look at snapshots of crumbling insane asylums and quick sketches of endless, festering swamps. Much feels like it’s missing, but we don’t miss it, because it’s easy to imagine what is left out.

And imagination is key here, because imagination may be the only possible way to save ourselves, to find some way to live a good life even as the blight spreads in and outside the text. Solutions are few and far between; beauty rots; but still, we can dream.

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

Omit needless words.

Omit needless words.

Muslim sections her stories into four groups: Animals, Children, Instead of Human, and The Age of Blight. Some of the stories seem loosely connected by the repetition of place names (particularly Bardenstan and Outerbridge) and by vague references to disasters. A note at the beginning of the book says, “Bardenstan is a suburb. In 2115, something will happen that will put Bardenstan on the map. It will be known throughout history as the site closest to the epicenter of the fallout. Outerbridge, on the other hand, remains the only part of America where plants are still grown in soil.” |

We may assume, then, that we are in the territory of science fiction, but the stories themselves are more like poetic fragments of myth and nightmare than straightforward extrapolation. While a writer like Paolo Bacigalupi creates at least quasi-believable future scenarios (scenarios of resource scarcity, war, misery), Muslim seeks something else, something more visionary than speculative. At the same time, though, these stories feel like they come from a place of terror: terror at the shape of the real future we most likely will provide for this planet and its inhabitants, human and other-than-human.

It is the other-than-human characters that Muslim writes best, in fact. The stories in the first section of the book, devoted to animals, are evocative and unpredictable, unnerving; their images linger long in the imagination. Consider this first paragraph of the first story, “Leviathan”:

It was the day the ancient sea beast finally reached your shore and died there. Unable to resurrect your sole prize after trawling the ocean floor for eighteen years, you secretly wired a pair of artificial gills inside it. And how the makeshift gills hissed telltale breathing at the rate of two intakes per minute! How the cameramen captured the triumphant moment when you presented the creature long believed to have become extinct during the Silurian Period. The cameramen filmed you as you supervised the lowering of your fine catch into a temperature-controlled water tank. They cheered when you gloated, “I told you I was going to get the sucker.”

We know little about the human protagonist in this story, the “you” it addresses. The character is some sort of Captain Ahab, and that literary resonance may be enough, perhaps, for us to imagine some motives and desires. The creature itself is a bit more vivid, though its outline shimmers at the periphery of the story’s vision. What we have at the end of these two pages is not so much character or place, but sense and image: organic life then death then mechanized life then death again: “[The engineers] knew you were going to make up stories to explain the creature’s swift demise—not at your hands, of course, but to a believable catastrophe.” The story ends with what feels like a nod to Kafka’s “Report to an Academy” (the tale of an ape captured and brought to the “civilized” world of humans and put on show, an ape that now speaks to learned men about apeness, which he, to some extent or another, has escaped, though he will be condemned forever to be a freak, a thing neither human nor not-human). Muslim’s story is different, though, because the pursued animal is dead by the time the captain gets it. The animal’s life becomes illusion, as does its second death.

The difference between the two stories, Kafka’s and Muslim’s, is resonant: instead of a non-human animal trapped in a human world, a world of human desires and knowledge, her human is trapped with a dead animal that seems to be alive, and then must be given a story that fits the very real death after the fake life.

The difference between the two stories, Kafka’s and Muslim’s, is resonant: instead of a non-human animal trapped in a human world, a world of human desires and knowledge, her human is trapped with a dead animal that seems to be alive, and then must be given a story that fits the very real death after the fake life.

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

Stories must account for real death and fake life.

Stories must account for real death and fake life.

|

| photo by Kenny Hotz |

The next story, “The Wire Mother”, continues the theme of scientists and animals and death. It tells the at-least-partially-true tale of psychologist Harry F. Harlow, who tortured monkeys for the sake of his science. The story begins with an epigraph from Harlow’s paper “The Nature of Love” (slightly simplified):

Our first baby had a mother whose head was just a ball of wood since the baby was a month early and we had not had time to design a more esthetic head and face. This baby had contact with the blank-faced mother for 180 days and was then placed with two cloth mothers, one motionless and one rocking, both being endowed with painted, ornamented faces. To our surprise the animal would compulsively rotate both faces 180 degrees so that it viewed only a round, smooth face and never the painted, ornamented face. Furthermore, it would do this as long as the patience of the experimenter (in reorienting the faces) persisted.

The story begins:

Imagine yourself having to choose between two mothers. There’s one like myself, once fondly called an iron maiden—a body made of wire, rows and columns of sharp teeth; coldly tells you truths you prefer not to hear; gives you food and milk and perhaps, lots and lots of material things to satisfy your need for survival and superficiality. Then there’s another mother out there—a flimsy and soft-spoken one called the cloth mother. And this mother is made of terrycloth. She gives you no sustenance but seems to hug you back the way you have always wanted to be hugged—not too tight and not too relaxed. She also maintains a characteristic flush that you associate with affection. Now, be honest. Which mother do you think is better? Better, meaning, the one you’d spend the most time with. This was the premise behind Harry’s little prank about the nature of love; and by prank I mean experiment.

The story continues from the wire mother’s point of view, and that point of view cannily, disturbingly shifts its “you” from that of a general reader to Harry himself. As in “Leviathan”, where the “you” is us, and the us is the desperate, failed Ahab as well as the people who want the desperate, failed Ahab to have been successful and to display his success for our entertainment (and by entertainment I mean knowledge/ I mean prank/ I mean experiment)—as in “Leviathan”, the movement in the reference for “you” indicates we, dear reader, are complicit in torture, cruelty, pain, death.

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

Don’t let your reader off the hook. Impale us.

Don’t let your reader off the hook. Impale us.

The third story, “The Ghost of Laika Encounters a Satellite”, is perhaps the most immediately painful in the book. For animal lovers, its sadness may be almost unbearable, like pure distilled essence of Where the Red Fern Grows. Again, it is based on a true story, the tale of the dog Laika, who in 1957 became the first animal to orbit the Earth. An accurate account of Laika’s demise was not made public until 2002. Muslim’s story is told from Laika’s point of view, and Laika relates her own death:

…they locked me inside, and maybe for the first time I felt lonely. I was shot into space.

There’s no pleasant way to state what happened next, so I’ll just say it. The core sustainer failed to automatically disengage from the payload, and I died by extreme overheating a few hours after launch.

The story continues into memories of cars and people and Earth landscapes. Knowledge of the horror of Laika’s death infuses these imagined memories (dreams?) with unforced poignancy. Muslim’s care with shifts of point of view continues in the final paragraph:

Outside the car, I think I see you. You are body. You are highway. You are bridge. You are water. You are mountain. You are space. You, who summons and aches to refill what has been lost, open your solar-paneled eyes. Look at me.

We have been seen, and we are implored to see. There are no borders here in Laika’s conception of us. We are ourselves and our landscapes. We are bodies, we are things made, we are things grown, we are organic and inorganic, specific and general. Our selves are inseparable from our world. We feel, we summon, we ache. And something has been lost. What is it, though? Can we perceive it? Laika’s imperative is for us to look at the ghost of what we killed as we built our knowledge-world, but are we able to see such a ghost?

Elementary Principles of Composition

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

Show the ghosts of what got killed by the engineers of knowledge-worlds.

Elementary Principles of Composition

The next two sections (“Children” and “Instead of Human”) reveal the challenge that a book such as this presents itself, because after the precision of the first section’s surreal explorations of pain, loss, perception, and epistemology, where is there to go?

I must admit disappointment, but it is the sweet disappointment of having experienced something exceptional and then followed it with something of good craft and good thought, but not excellence. The stories in the middle sections are not bad stories, but they feel more predictable and less evocative to me: too storied, too bound to canned expectations and narratives, too familiar after the opening section’s demolition of any expectations we might have packed for the journey through this book. There are ghosts in these middle-section stories, as there were before, but now they are the sorts of ghosts we know from other stories, as are the many doppelgangers here (if not quite the zombies, who lounge like lizards and stand for nothing except the eternal fact of brokenness). Recognizable props carry the weight of old stories’ histories, a weight with its own gravitational force. Muslim is a miniaturist, and short bursts don’t provide escape velocity from that force, which holds the stories down.

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

Escape the gravity of the familiar.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

The book returns to its visionary strengths with the last of the Instead of Human stories, “Beautiful Curse”, where the mysterious fallout of 2115 in Bardenstan leads to radioactive mutations and children with tentacles. Here the human and not-human are once again in question, and here, once again, fear, anger, and hunger rule. There’s an allegorical quality to the story, a Statement about insiders and outsiders (Statements, too, wield their own gravity, making it tough for tales to jump and fly): “Outerbridge, the only place in America where crops are still grown in soil, does not take kindly to deformities. There are town where physical aberrations are tolerated. Bardenstan, for example. Anyway, that’s another story.” The narrator ducks away from the urge to tie the tale up in a ribbon of moral, but the glimpse of that ribbon, the desire for it, remains stated. The narrator’s yearning to explain what the story means gets thrown aside by the primitive, even atavistic, hunger that follows: “I have plenty of stories left in me. Now they’re mostly about the hunt, the hunt, the unending hunt.” And then, metamorphosing once again, the tale ends (like a phantasy from Freud) overwhelmed by a desire to devour the mother.

The final section, which shares the title of the book, begins with “Day of the Builders”, a story of colonialism and assimilation. The Builders of its title have an allegorical name, but their behavior is familiar from countless histories, the behavior of conquerors, missionaries, orientalists, and imperial clerks. At eleven pages, “Day of the Builders” is the longest story in the book, and it uses its elbow room well, showing a whole process of invasion, acculturation, and erasure that most other writers have required at least one whole novel to achieve.

“The Quarantine Tank” moves us from the somewhat schematic progression of “Day of the Builders” back toward the strange ambiguity (or ambiguous strangeness) of the book’s first section. Here, invasion and acculturation and perhaps even erasure are a presence, but exactly what sort of presence is difficult to say. There is a chemical plant with a mysterious tank in it. There are rumors of a Great Beast. There is a grandfather and elders. There are fields of lavender. The elders have told stories of the Great Beast and the quarantine tank, but is there a Great Beast, and is the tank a quarantine tank? And what was the Age of Semiconductors? And how can you survive touching the chain-link fence of the chemical plant? Who are the men with the “sinewy bodies” who cultivate the lavender, and what is their relationship to the “feral handlers” tamed by dogs and the “plant operators in green hazmat suits” who are summoned by an alarm in the chemical plant? Why are the hedges around the chemical plant fake?

We do not know. We cannot know.

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

Show the things in heaven and earth not dreamt of in your epistemology.

All we know is that the alarm sounds and the lavender is cultivated and the civilized dogs with their tamed, feral handlers stop for a drink from the lagoon.

And it is no longer the Age of Semiconductors.

A Few Matters of Form

In “The First Ocean”, elders who remember seas, beaches, and sand lie about the seas, beaches, and sand to young people (are they young? are they people? “their battery panels had just been replaced to last for another three hundred years”) who do not yet understand the courage of “hiding inside a glass cage” and do not know that a little piece of grey plastic is not a pebble from the long-lost beach. They conjure the lost world in their imaginations.

Does it matter that what they imagine has little to do with what was there before it was lost? How accurate must we be in our dreams?

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

Dreams must only be accurate about death.

And then we end with “History of the World”, a kind of parable or allegory or something-or-other about people who hang off of cliffs, and bodies become carrion. It is in this story, in fact in its last line (the book’s own last line), that we learn about the “age of blight” of the title. It is lowercased, and we do not know its relationship — more common, clearly — to the Age of Semiconductors. It is inspired by vultures.

The movement of this final section, which we could say is the movement of the Age of Blight toward the age of blight, is a movement from imperial invasion to acculturation and re-historicizing to erasure of the past to the past as paradox and aporia and then myth and then dream — ending not with that dream, but with the brute fact of a warm corpse and scavengers in a story called “History of the World”.

Words and Expressions Commonly Misused

Some corpses are warmer than others, warm enough to emit bromides. Language itself is a tool of the blight. (Writer, blighter.) Branders and pitchmen turn words to dreams of plentiful life and no drive to death. Politicians poison policy with eloquence. Dissemblers assemble.

What might we scrawl on the blasted heath? What can stories scry?

How might we express our lives as corpses?

What have we seen, dear reader, by which I mean: What have we read? What is our world, our history?

What can we say as we hang here on the cliff, the vultures circling?

∅ Elements of Style for the Age of Blight:

What do you want the detritivores to remember of you?

|

| Wikimedia Commons |