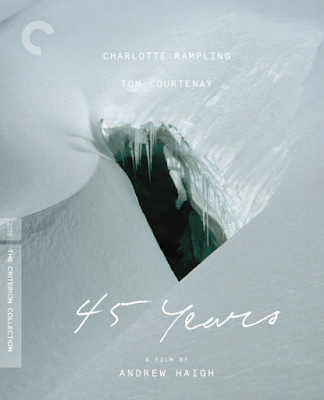

45 Years

Andrew Haigh wrote and directed one of my favorite films of the century so far, Weekend, and his 2015 movie 45 Years is based on David Constantine's breathtaking short story "In Another Country" — as rich and perfect a story as you're ever likely to read.

For these reasons, I put off seeing the movie for a long time, because I feared it could not live up to my hopes and expectations for it.

And no, it couldn't live up to my hopes and expectations, and my hopes and expectations did, indeed, get in the way — but it's still an impressive film. In particular, the performances and the cinematography are magnificent.

The plot of 45 Years is simple, and starts right from the second scene: An older couple, Kate and Geoff, are getting ready to celebrate their 45th wedding anniversary, having not been able to celebrate their 40th because of Geoff's heart bypass surgery. That week, Geoff receives an official letter letting him know that a body has been found encased in a melting glacier: the body of Katya, his girlfriend before he met Kate. He and Katya were hiking in Switzerland in 1962 when Katya fell into a crevasse. Kate knew this story, but hasn't thought about it in many years. Geoff explains to Kate that to make their traveling easier, he and Katya had told people they were married, and thus he was the next of kin, a detail Kate claims she never knew. The rest of the film is about the tension that then enters Kate and Geoff's relationship because of this new knowledge. Geoff can't stop obsessing about his past with Katya, and Kate is somehow deeply threatened and hurt by it all.

The problem I encountered after a first viewing of 45 Years was that I just didn't buy the premise. This is strange, because it's the same premise as the short story. But Constantine's emphases are rather different from those of the movie — his concern in the story, and in much of his writing, is at least as much with the passing of time and the power of memory as it is in the characters' relationship. The ending is entirely different (very powerful, very sad).

Haigh is relatively young (he's a few years older than me — very young!) and his interest is less in memory and time than in the relationship. This is a somewhat more dramatic interest, anyway, and thus a good one for a narrative film. But it puts an awful lot of burden on Kate's reaction to the letter Geoff receives and his reaction to it. After first watching the film, I couldn't help wondering why she cared so much. After all, she's had 45 years with this guy. He's clearly a bit doddery. What is the big deal? How could they have gotten through 45 years together if she had such a fragile sense of their relationship that it could be threatened by a woman who'd been dead for half a century?

I had a sense that there was an answer to this buried in a couple of quick moments, but I feared I was perhaps imposing my own reading on the material, so I went back and reviewed them. I think my reading, while hardly the only possible one, is supported by the evidence, and that made me appreciate the film's subtleties much more.

The scene where Kate climbs into the attic and views old slides of Katya is obviously one of the key moments in the film, beautifully shot and acted, a truly great moment of cinema. It is also the key to my interpretation of Kate's character: She sees that Katya was pregnant, yes, but she also sees (or imagines she sees) other things that shake her world to the core.

In a very brief conversation with Geoff, she says that all of the choices of their lives, even the biggest (whether to have children) have been affected by Katya — what kind of dog to get, for instance. Geoff denies it, and the scene moves on. But this is the moment that makes Kate's character believeable to me. Her experience of their marriage for 45 years has been that it is an authentic relationship based on her own personal qualities. But now she suspects that in some crucial way it's all been a fraud: that she has been a substitute for Katya (even her name suggests this). Geoff never loved her, really: he loved her for her ability to be almost-Katya.

The lack of photographs is important. Kate and Geoff discuss this (innocently) early on, how they have no photographs of each other, and then Kate finds out why Geoff has so resisted pictures: Because the only photos he really wants are ones of Katya.

Watching the film from the beginning with all of this in mind makes Charlotte Rampling's performance even more impressive. Her face is stunningly expressive with just the slightest shifts of her eyes or mouth, and her body is lanky, which she uses to great effect: at one moment, she is regal; at another, awkward. Tom Courtenay is also extraordinary: he dodders around, but at least some of his doddering seems strategic, as if Geoff isn't quite so far gone as he seems, as if perhaps what he is is someone desperately trying to keep a certain truth from bubbling up.

It's an interesting film, though not one I have a lot of interest in revisiting (whereas I watch Weekend at least once a year), perhaps because Haigh's laser-focused interest in interpersonal dynamics, tiny moments of domesticity, and the details of marriage are not ones I share. David Constantine's own interests are different — "In Another Country" (as well as most of his other fiction) is about a marriage, yes, but it's also about time, memory, and loss in a way that Haigh's much more materialist vision simply is not. But Constantine is strongly influenced by German Romanticism, whereas Haigh, it seems, is, despite his poetic inclinations, a social realist to the core.