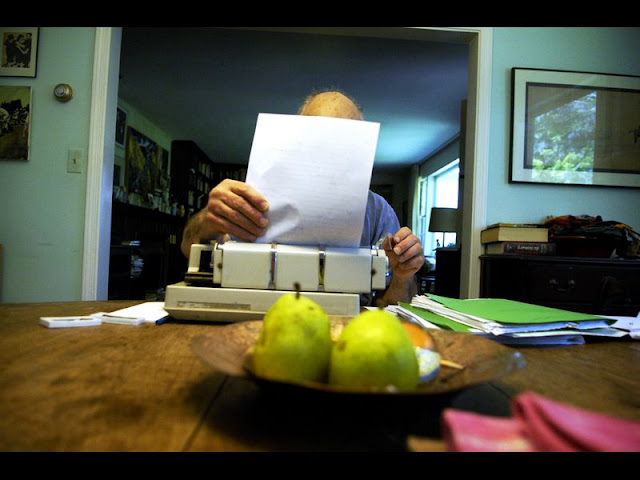

Stephen Dixon (1936-2019)

|

| photo of Stephen Dixon by Christopher T. Assaf, Baltimore Sun |

Sometimes, I would get annoyed when I saw Stephen Dixon's byline, because sometimes it felt like he was everywhere. Pick up a literary magazine, scan the table of contents: familiar name, unfamiliar name, Stephen Dixon. For a while, too, I thought there was a uniformity to his style: long, headlong sentences, endless paragraphs, the minute thoughts of boring white hetero guys. Everywhere. Stephen Dixon.

These feelings of annoyance never lasted very long, because I'd always end up going back to one of Dixon's collections, particularly The Stories of Stephen Dixon and, more recently, What Is All This?: Uncollected Stories. Open a random page of either of those books and you will find energy, weirdness, insight, humor, tragedy, wonder. And while, yes, there's often page after page of hetero white guy yammering, we mustn't forget that Kafka was among Dixon's favorite writers, and Dixon never gets too far away from Kafka's sense of the absurd, the horrifying, the fantastical. (Read "The Hole" in The Stories, read "Down the Road" in The Anchor Book of New American Stories.) He also loved Chekhov, and eventually married a Chekhov scholar. "Chekhov," he said, "could be the greatest writer who ever lived." It's a position I respect.

And as to those hetero white guys yammering: Yes, the last thing the world needs is more yammering from hetero white guys, but still, this is the yammering that has shaped a lot of society for the last [insert preferred number here] decades and centuries, the yammering that has scripted our psyches, even if (especially if?) we are not exactly one of those qualities (hetero / white / guy), and seeing it on display as it is in Dixon's work, seeing it laid out as if on an operating table or under a scientist's microscope, feels, to me at least, somehow empowering, or at least less threatening, because here it is, the gunk of mainstream thinking, deprived of honor and glory, not dressed up in the finery of official statements, not disguised by the politeness of social graces, and dead on the page there where I can laugh at it and scorn it and turn the page (my power over it). Dixon's hetero white guy characters' sputum of consciousness reminds me of how pitiful these people's existence is, how primitive their desires, how narrow their lives, how shallow their dreams — and it would be fine if it only went that far, because that's subversive enough when you live in a world shaped by eons of those desires — and it would also be cynical, mean, and in its own way a narrowing of my (the reader's) imagination — but it doesn't only go that far, because what you also get are the resonances and convergences with your own thoughts and experiences, and you (I) must grapple with your (my) overlaps, the places where, despite all sorts of differences, I, too, am this person I have been feeling contempt for, this familiar human being conjured in my imagination by Dixon's words. There's more to the effect: Dixon's work allows me to see that these characters are not without their own contradictions, and that with every day lived by any of us, contradictions rhizome through our biographies. That's one of the things Dixon's novels in particular show through their accumulations of incident and juxtapositions of events. Gould, for instance. It took me a long time to be able to get through that novel — because yuck what an asshole! Gould spends much of the book as little more than an engorged penis with language capabilities. He's so awful he verges on a blunt caricature of a hetero white guy. And yet. The book is a journey, for him and for the reader, and it becomes strangely moving by the end, and even — though I cringe at the phrase — a book of moral insight. Partly (largely), this is because of Dixon's sense of form, and with the character of Gould in particular, that sense of form led Dixon to continue the character in 30: Pieces of a Novel, an even more remarkable book than Gould, where the character is given even fuller life, and different life.

As much as he was anything else, Stephen Dixon was a formalist. He was a formalist in his syntax, diction, punctuation, and sense of the page; he was also a formalist in how he used parts to create wholes. This is vividly clear with his great novels of the 1990s: Frog, Interstate, Gould, 30, all of which, to some extent or another, rely on the junctions and disjunctions of parts. A writer who is, at heart, a short story writer can, with a strong sense of structure, become an interesting novelist by accumulating pieces, fragments, and stories; a writer who is, at heart, a novelist and who tries to write short stories often ends up with work that just feels thin. Dixon's gift was that of a short story writer; his insight was to see that that didn't mean he could only write short stories. That insight was clear from the title of a novel that long remained unpublished, but which he began in the 1970s: Story of a Story and Other Stories: A Novel.

Now Stephen Dixon is dead, after a long life. Though nominated for various awards, he never achieved much fame. He certainly never achieved the recognition he deserved. Partly, this was his own fault: He didn't want to participate in the rigmarole of publicity that is demanded of every writer these days, nor was his writing in any way trendy. Though he taught for a long time at Johns Hopkins (and was quite influential through that position), he doesn't seem to have spent a lot of time at writers' conferences, doesn't seem to have clamored to be on panels at AWP, never had a social media presence, didn't gladhand and logroll. He seems to have had a cantankerous streak and a definite stubbornness. His books didn't make much money, he bounced around from publisher to publisher, he said he had trouble keeping an agent. No surpise, really. You can imagine what agents and editors told him: "Can't you shorten your sentences? Shorten your paragraphs? Clarify the plot? Give us a character to root for?"

Here's something Dixon said in a 1995 interview:

Good advice for writers: Write very hard, keep the prose lively and original, never sell out, never overexcuse yourself why you're not writing, never let a word of yours be edited unless you think the editing is helping that work, never despair about not being published, not being recognized, not getting that grant, not getting reviewed or the attention you think you deserve. In fact, never think you deserve anything. Be thankful you are able to write and enjoy writing. What I also wouldn't do is show my unpublished work to my friends. Let agents and editors see it--people who can get you published--and maybe your best friend or spouse, if not letting them see it causes friction in your relationship. To just write and not worry too much about the perfect phrase and the right grammar unless the wrong grammar confuses the line, and to become the characters, and to live through, on the page, the experiences you're writing about. To involve yourself totally with your characters and situations and never be afraid of writing about anything. To never resort to cheap tricks, silly lines that you know are silly--pat endings, words, phrases, situations, and to turn the TV off and keep it off except if it's showing something as good as a good Ingmar Bergman movie. To keep reading, only the best works, carry a book with you everywhere, even in your car in case you get caught in some hours-long gridlock. To be totally honest about yourself in your writing and never take the shortest, fastest, easiest way out. To give up writing when it's given to you, or just rest when it dictates a need for resting; though to continue writing is you're still excited by writing. To be as generous as your time permits to young writers who have gone through the same thing as you (that is, once you become as old as I am now). To not write because you want to be an artist or to say you're a writer. And to be honest about the good stuff that other writers, old and your contemporaries, do too. And not to think that any stimulant stronger than a coupla cups of coffee will help your writing. Sleep helps it, keeping in shape, but little else, along those lines. And not to listen to God himself if he tells you that you aren't a writer and will never be one, if you still think you are a writer or can become a good one, or if you get a kick out of writing.For all his hatred of publicity, he gave some good interviews through the years. They're worth seeking out, as is his fiction. He may be gone now, but we should not let his writing slip away.