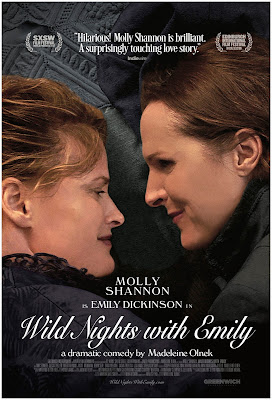

Wild Nights with Emily

A few years ago, I declared a movie about Emily Dickinson, A Quiet Passion, to be "one of the worst movies I've ever seen". It remains so.

Madeleine Olnek's Wild Nights with Emily is everything A Quiet Passion is not: lively, irreverent, joyfully artificial, poetic without being "Poetic", exuberantly cinematic, intentionally funny, and, in the end, quite moving. And while it is occasionally anachronistic, frequently campy, definitely uninterested in nuanced (or balanced) (or even fair) portraits of historical figures, and sometimes just flat-out bonkers, it's also a bit more accurate to Dickinson's actual life — and vastly more accurate to her legacy — than A Quiet Passion was.

But Wild Nights with Emily is more than a biopic. It's a movie about literary history, about how stories of writers (and artists of all sorts) get told and received. It says that even with truths in plain sight, most people prefer legends, because legends are soothing and familiar. Legends reinforce dominant values, sculpting stories of the past into a shape that fits the desires of whoever has taken control of the story. While Wild Nights with Emily does tell some pieces of Dickinson's life story, it tells at least as much about how her writing got written, read, and received. It shows people trying to take control of her story, building what Adrienne Rich called the "pious or clinical legends" about her, all the time refusing her fire. Within that story is a story of the way the poems were disfigured by editors who wanted them to be more conventional, and the way the letters were disfigured by people who wanted Dickinson herself to have been more conventional. Entire pieces of Dickinson's life and work were literally erased.

Drawing particularly from Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson's Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson, Olnek's film portrays a loving relationship between Dickinson and her sister-in-law, a relationship that has frequently been questioned, doubted, and minimized by readers and biographers. Wild Nights with Emily has great fun giving a middle finger to all such questioning, doubting, and minimizing. In doing so, it tears down the calcified image of the fragile, reclusive spinster Emily and replaces it with an image far more complex, vigorous, and interesting, while also exploring how the narrow idea of Dickinson got planted in the public mind, and why that public mind might have preferred an effete, ethereal Dickinson to a passionate, embodied one.

The film is a tonal rollercoaster, using all sorts of items in its cinematic toolbox: caricature, fantasy, voiceovers, text on the screen, musical sequences, and a wide range of acting styles, from more-or-less naturalistic to archly affected, even wooden — by seizing comedy as its mode, the film shows us a brilliant woman surrounded by cardboard cut-outs of human beings. Sometimes the effect is hilarious (the moment with Ralph Waldo Emerson is one of the funniest things I've seen in a long time), sometimes just weird, and I appreciated the weirdness as much as the comedy, because it sets things a-kilter, it alienates, and it allows us to feel some of the sense of outsiderness that the Emily of the film (and, I expect, the Emily of history) herself is shown to feel. While the costumes are generally "realistic", the actors sometimes make no bones about the fact that they're playing make-believe and dress-up. The script bounces around throughout Dickinson's life and afterlife, presenting scenes as nonlinear vignettes, making the whole something of a Brechtian epic, but with more wacky humor. The closest analogue I can think of is another recent historical film that I thought was tremendously well done: The Favourite. Olnek's film is more anarchic than Lanthimos's, though, more scattered, more punk. Where The Favourite demolishes the costume drama from within, Wild Nights with Emily assaults it from all sides. Even though you could pretty much give this movie a G rating, it nonetheless feels at times like John Waters directed it. (And I mean that as a great compliment!)

The genius of Wild Nights with Emily is clearest in Molly Shannon's speaking of Dickinson's poetry. She treats the words not like things deserving reverence, not like "Poetry", but rather speaks the text in a way that gives each line an offhand power. It's a way of speaking that honors the constant, but unpretentious, surprises throughout Dickinson's poetry — a way of speaking that gives life to the genius in the words. The other way of speaking, the one so common in films and audio books and poetry readings (cf. A Quiet Passion), that seeks to emphasize just how poetic it all is, is parodied in two scenes: one where the young Emily and young Susan recite Shakespeare; the other where Helen Hunt Jackson recites her ponderous poetry to an adoring audience. This, the film shows us, is exactly what Emily Dickinson's poetry is not. To read her poetry as if it is Something Very Poetic is just as wrong, and much less fun, as reading it to the tune of "The Yellow Rose of Texas". Shannon does well, too, with excerpts from Dickinson's letters that the script turns into dialogue, a practice that can often prove fatal, since most letters, historically, were not written in the manner of everyday speech. Given how adroitly Shannon handles the text, actors ought to study her performance closely. It's rare to hear poetry given such life by an actor without it feeling forced.

Wild Nights with Emily ends with a split screen that at first feels a bit obvious and on-the-nose, but then seems somehow perfect: bittersweet and sad, ironic and utterly earnest. The whole complexity of the film is apparent in the juxtaposition of the two shots: one of intimate care, the other of public distortion.

She never had time in all the vivid, thrilling, incessant programme of night and day, summer and winter, bird and flower, the terror lest evil overtake her loved ones the glory in their least success — never stopped in her flying wild hours of inward rapture over a beauty perceived or a winged word caught and spun into the fabric of her thought— to wonder or to care if no one knew she was or how she proceeded in the behavior of her own small tremendous affair of life.

—Martha Dickinson Bianchi,

Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson