Really Persistent: Kate Zambreno and Bo Burnham

1.

Early in her new book, To Write As If Already Dead, Kate Zambreno notes that "Kafka's insurance firm was full of aspiring poets, a reminder that it is fairly commonplace to want to be a writer or poet. It is more unusual to stay a writer despite lack of status or outward success, to sacrifice sanity, sleep, positive well-being, health, to instead dwell in a life that is one of almost constant paranoia, oscillating between horror at invisibility and nausea at visibility."

One of the things about Kate Zambreno's work that I particularly appreciate is the way it refuses to be positive and hopeful. (More than anything else, that's what links her to Jean Rhys, a writer she has frequently referenced overtly and covertly.) To Write As If Already Dead makes the life of a writer seem just flat-out awful; it also makes the life of a mother seem flat-out awful. A mother who is also a writer? Sheer, unrelieved torture.

Nevertheless, she persists.

Zambreno's narrator keeps writing books and keeps having children. It would be darkly hilarious if her travails weren't so gut-wrenching, particularly as she navigates the sadistic bureaucracy of American healthcare.

I choose to believe that the actual Kate Zambreno's life isn't quite so awful as it is in her books, because the books, for all their apparent extemporaneousness, are carefully constructed. One of their repeated subjects is the fact that the I of someone named Kate Zambreno out in the world is not the I of the narrators of her books, similar as they may seem.

What is absent from Zambreno's books is at least as important as what is present. For instance, there is nothing much in this book about her love for her children, which I assume is present, strong, and real — because if not, then she's a masochistic monster, given how horrific her portrayal of pregnancy and motherhood is. Similarly, I assume there are times when she actually likes writing and publishing, since she has published a pile of books instead of doing something she might enjoy a bit more, like coal mining. But she doesn't need to portray the life of a writer as occasionally joyful — there are countless other books, magazine articles, blog posts, Tweets, newsletters, motivational posters, and needlepoint samplers all extolling the wonders and pleasures of the writerly life, the nobility of the writing vocation, etc. Similarly, pregnancy and motherhood are popularly celebrated as glorious miracles even as this country's social policies (or lack of them) make having and raising children expensive, difficult, and dangerous unless you are a (white) person of means.

To instead dwell in a life...

Most of Zambreno's books pose, sometimes explicitly, the question, "Why go on?" Why keep making art despite the fact of the world's indifference, or despite the fact of occasional, unsatisfying, ephemeral success? Why continue in precarious jobs at colleges that require you to teach even when you are desperately ill, and offer, at best, health insurance plans that soak up most of your income? Why not do something else? Why keep doing this? Why keep living? Why bother?

To instead dwell in a life...

To instead dwell...

To instead...

("What are you saying?" the small boy asked.

|

| Inside |

2.

In the contest of "Imagination vs. Reality," I am drawn to "versus." It creates the security of a clearly-defined dichotomy. "Versus," a word nostalgic as mom's apple pie, harkens back to the duality Western consciousness was built upon and which, in this postmodern age, has flown away like the train that flies out the fireplace in Magritte's picture.

—Dodie Bellamy, "Incarnation"

Soon after reading To Write As If Already Dead, I watched the new Netflix movie by Bo Burnham, Inside. Here, too, we have a compelling work of quasi-autobiography that mixes, melds, and mangles modes to create a piercing commentary on contemporary life, art, and mental health. It's a cinematic, pop culture cousin to Zambreno's books, a work by a person painfully aware that he is stuck with himself.

Early in Inside, Burnham wonders why he should bother trying to continue as a singer and comedian when the world is falling apart and he's a straight white guy, the last person who ought to be seeking attention in the culture right now. Why not just shut up? So he goes silent for a few seconds. Then: "I'm bored."

This is a variation on the schtick Burnham presented in previous comedy specials, but he's no longer a smart-ass kid with more talent than purpose. The previous shows were amusing diversions with glimpses of unrealized depths; now, after not performing for five years and developing his talents in various other ways, Burnham has finally found a way to put his deconstructive and metatextual tendencies, self-deprecating-but-also-self-promoting style, and serious cleverness to use in a richer way than before. Inside, for all its humor and entertainment, is a portrait of desperation and breakdown, a millennial's one-man-band production of Krapp's Last Tape. The pandemic is the (unspoken) cause of and excuse for Burnham's life indoors, but quickly enough we see that this is also what clinical depression does. The comedy, the songs, the need for attention all are shown to be, simultaneously, symptoms and treatments for the situation of being stuck with your self.

There are lots of extraordinary moments in the movie, but one that haunts me is the bridge material in the song "White Woman's Instagram". All the rest of the song mocks the shallow, derivative, kitschy sorts of things one might see on a stereotypical Instagram account of a certain type of white woman, but the bridge gives us something else: a photo of the eponymous woman's mother with a heartfelt caption about the tenth anniversary of the mother's death. And then, just as we've processed this information, the song leaves the bridge and returns to mocking the generic material. (There is a visual change, too, as the aspect ratio during the song is similar to an Instagram box, but opens out to widescreen format for the bridge, then returns to the square format for the rest of the song.) This change in the song does a few things at once. It points to something good and meaningful within a parade of empty, meaningless gestures. It suggests that there is a more complicated person behind the Instagram account than generally presents herself. And, most importantly, it proposes that the posting of the generic and apparently shallow material is in some way or another connected to the statement that this particular white woman is "still figuring out how to keep living without you", wanting to prove that her life is okay, that "your little girl didn't do too bad". We hear the rest of the song differently, and may now dislike the mocking because we have a different perspective on it. Or we may not even hear it as mocking anymore, but as the representation of a person just trying to make some beauty and pleasure in her life in amidst the pain.

The full presentation of the white woman's Instagram account mirrors Burnham's own efforts throughout the movie to keep going, to make something that doesn't just relieve boredom but provides some reason to stay alive.

|

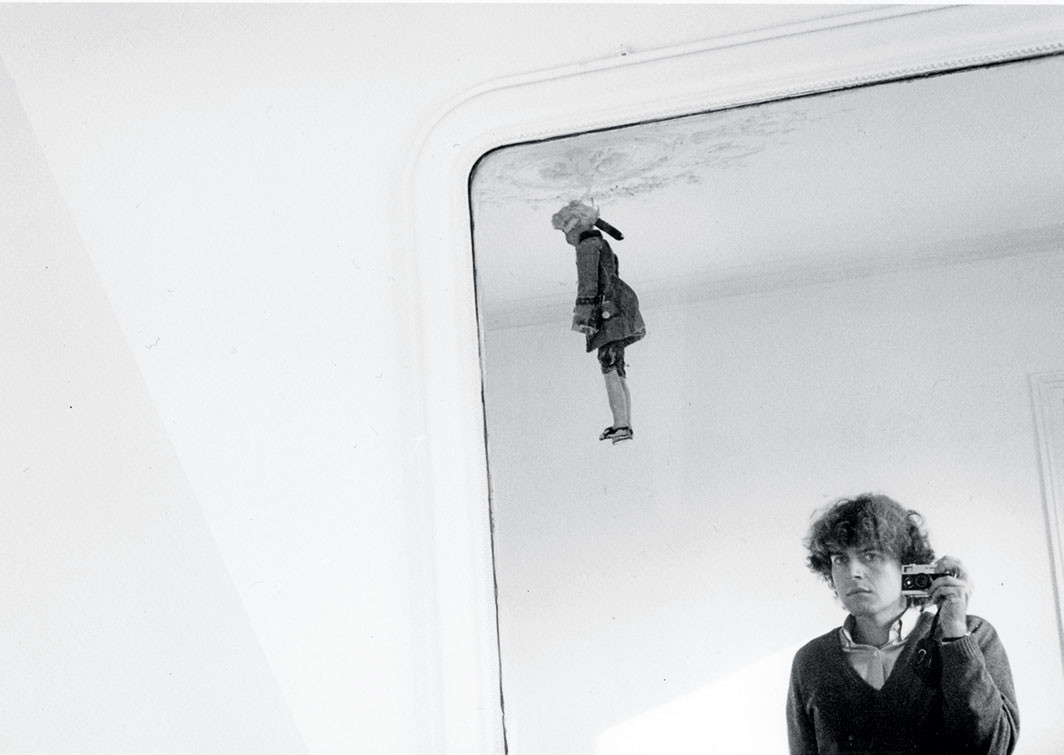

| Hervé Guibert, Autoportrait et pantin, c. 1981 |

3.

To Write As If Already Dead is a book about Hervé Guibert and his autobiographical novel of AIDS, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life; it is also a book about not being able to write a book about Guibert and his novel because a child, a new pregnancy, precarious employment, and a global pandemic all get in the way.

Were Zambreno's book fiction, we might say its circumstances seem too on the nose for the subject matter, too contrived and symmetrical for writing about not writing about Guibert — what novelist, after all, would strain credibility so much as to add not only an unplanned and difficult pregnancy, but also a global pandemic!? (Reality scoffs at the subtlety of fiction. Random example: no self-respecting fiction writer would set a mass shooting in the parking lot of a store called Safeway.) Sometimes, the one consolation a writer can take when faced with immense obstacles is that obstacles are good material. Zambreno wonders why she, a contemporary American woman in a heterosexual relationship, has any authority or credibility to write about Guibert, a queer French man who died of AIDS complications in 1991. The circumstances of life then provide her with plenty of material with which to write a productive exploration of Guibert, one based not on exact overlaps, but on symmetrical experiences of hardship, healthcare, and the sometimes mysterious desire to write about oneself.

Guibert was a photographer, filmmaker, and writer who chronicled his life through numerous books until his death shortly after his 36th birthday. To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life is the book that made him famous in France and continues to be his best-known writing, a barely-fictionalized memoir-novel that includes a character obviously based on Guibert's late friend Michel Foucault. The book was hugely controversial on publication because it revealed a lot about Foucault's private life that was not previously stated in public, including the fact that he was HIV positive.

"In many ways," Zambreno writes (with words that might apply equally to herself), "Guibert is more of a diarist than a novelist. The diary feeling is a shape of fragmented consciousness. Then what does he mean when he writes in Compassion Protocol, a classic aphoristic flourish closing a section, 'It is when what I am writing takes the form of a journal that I most strongly feel that I am writing fiction'?"

4.

Inside is a comedy special about the failure to create a comedy special. Like any good autofictionist, Burnham includes a metatext, the story of the creation of the story. The process of making the movie is itself a strand of story woven through the whole.

We see the struggles familiar to any creative person: the struggle to pull disparate pieces together, the struggle to make a coherent whole, the struggle to deal with work that inevitably fails to live up to your hope for it, the struggle to be self-critical without being self-hating.

But there are other struggles, too. For instance, the terror of finishing. Burnham (or the character he plays) had not planned to spend a year putting together this movie, but he also hadn't planned to be stuck at home all that time. Finishing becomes, itself, terrifying. He struggles for an ending, at one point even rejecting the idea of ending, because at least if he keeps working on this project, he's got something to do, some meaning in his days, some reason to live.

There's more, too. Burnham becomes Narcissus looking into the pool at his reflection, and technology allows him to refract that, to become Narcissus looking at Narcissus looking at Narcissus. Maybe, with one more frame around himself, he will become more beautiful, more appealing, more entertaining. We do not see him watching other movies, listening to other music, interacting in any way with another human being. He is trapped in a room with only himself for company.

This is not just a darkly comic musical self-portrait — it's also a horror movie. Call it Saw: Myself.

("What are you saying?" the small boy asked.

5.

The structure of To Write As If Already Dead is two sections, with the second broken into titled subsections. Guibert, and the attempt to write a book about Guibert, is a topic throughout, but the first section of the book, titled "Disappearances", primarily focuses on ideas of friendship, especially friendship among writers and women. The second section, which shares the title of the book itself, is more varied, with subsections beginning with diaristic titles ("Yesterday", "December 26, 1988"), then more enigmatic ("Deadline", "Contracting", "Like a Dead Man", "The Weep and Ooze of Poison"), and sometimes straightforward ("Bitchy Prose", "Sleepless Nights", "Fibroscopy"). A section titled "Success and Failure" reads:

When my book is rejected everywhere, I jot down a quote from the diaries [of Guibert]: "it is perhaps preferable to circle around the idea of the novel, to dream it ... and to botch it, rather than succeed, since the successful novel is perhaps a very banal form of writing." I wonder when I submit to full-scale revisions of the novel, the months and months of trying to make everything perfect, nothing too difficult, whether I'm gettting further and further away from the moment of process, the private impulses, that I was hoping to document. It is the failure of Guibert's novel that interests me — the rushed, passionate, desperate, ferocious character of it. As opposed to all of the polished turds being published now.

I read that passage over and over. All the polished turds being published now.

I've been struggling, over the last few years, to write material that might offer anything of interest to an audience beyond myself and maybe a couple other people, so I am a sucker for such sentiments. I am wary of the self-congratulatory trap of those ideas, though. It's entirely possible that there's lots of polished turds getting published, but also, equally, simultaneously, that what I myself am writing is unpolished turds. (Both should be flushed into the sewer.)

Still, there's something to Zambreno's insight beyond sour grapes. When reading for fun (whatever that means) these days, I find myself drawn to writers like Kathy Acker, William Burroughs, Dennis Cooper, Gary Indiana. Confrontational, disreputable, messy writers. Writers hard to like. The dead ones (Acker, Burroughs) unlike most anyone who gets published these days; the living (Cooper, Indiana) a reminder of how impossible it would be to have their careers today.

|

| San Salvatore Hospital, Pesaro, Italy, March 2020, by Alberto Giuliani |

6.

And then the pandemic. Both To Write As If Already Dead and Inside are works affected by the pandemic: Zambreno's book is interrupted by it, Burnham's movie is constituted by its conditions.

To Write isn't a strictly linear narrative, so references to the pandemic appear earlier, but by p. 117 (of 144) it's there to stay. A subsection titled "Nausea" ("How time freezes then speeds up. The winter of 2020, once my classes begin, I cannot work anymore on the Guibert study. I do not have the time anymore, and also I am overwhelmed by the extreme labor of my nausea...") is followed by a subsection titled "Plague" ("And then, the ambiance of paranoia of the spring eerily echoes the book I've been residing in."), the pandemic bringing the narrator back to Guibert: "The eerie parallels of the novel to now. The sci-fi feeling of isolation in Rome, where Guibert exiles himself — with Rome now, the vacant streets, the eeriness of emptied-out Spanish Steps. In two weeks New York is supposed to be where Italy is now."

Zambreno's writing begins to mirror the world it describes, losing order in cascading paragraphs and sentences. What had previously been separated is now all flow — a subsection titled "List" is a single four-page paragraph of syntax that never gets incoherent but does grow less disciplined, its borders fading into a frantic accumulation.

Inside accumulates frantically, too, but with less frazzle than anomie. The material for the comedy special tends to the antic, but the moments between, the moments of meta, sit quiet, empty, drained, hollow, flat. But punctuated with brief exclamations: anger, frustration, despair. We, the viewers, become the voyeurs. Sometimes the camera is visible through a mirror, sometimes it is positioned as a spy, the position we have been trained by the conventions of media and surveillance technology to read as the real thing, the unfiltered truth, the overheard and overseen and unmediated; except, gorged with reality shows and mockumentaries, we also know that the feeling of the real may be the most mediated, artificial feeling of them all.

Both of these pandemic products are broken into two parts. Zambreno's book has two sections, Burnham's movie includes an intermission (even though the movie itself is not quite 90 minutes long). The parts are different, if related. The pieces are sutured together, semi-colon'ed. To what purpose? Hard to say. Past and present? Before and after? Now and then? Who knows. Broken, because we are.

7.

I keep thinking about the absences in Kate Zambreno's writing. (I admire her ability to absent.) In addition to the absent assertions of love for children and partner and all that domestic stuff, there is also an absence of pop culture. There may be some passing references to pop culture through her books, but I don't remember any, and the references she returns to are all on the higher end of the high art spectrum, the high culture world, the high theory pantheon. I admire and appreciate this. Perhaps her strict allegiance to Literature is one of the presences that draws me to Zambreno's work. It's her most old-fashioned trait. Nowadays, at least in English-language writing, most people who reference the highs also feel compelled to prove that they are not contemptuous of the lows. If one discusses, say, Proust, then it's best to prove some cred with a hot-take on a superhero movie.

For all I know, in addition to loving children and her partner, Zambreno is also a huge fan of the Avengers movies. What Zambreno knows better than most writers these days, however, is that pop culture doesn't need publicity and difficult (in whatever way) art does. Our explications of blockbusters are drops in the hype ocean. Meanwhile, another hundred small press publications just got ignored.

Inside shows the shallowness of a life of popcult consumption. (A notable absence in the space the character lives in: books and art.) The reservations I have felt when watching Burnham's previous comedy specials were always based on the same feeling, a feeling that a lot of intelligence was being wasted on material that didn't need it. Gore Vidal once criticized something (I forget what) for doing well that which is not worth doing at all. It's a typical failure of youth. Before you've got some death in you, you don't realize how much of life is not worth doing at all.

That's the power of the quiet moments in Inside, the power of its failures. Burnham recognizes the waste of doing. It's the hideous insight of his vow of silence quickly followed by, "I'm bored." There's the terror silence reveals, the fear inaction brings forward, the absence of self when you aren't screaming out, "I, I, I!"

But maybe this isn't a pop culture problem. Why is high art worth doing? What do we get from all our grad school theorizing, all our textual difficulties, our transgressions and subversions and deconstructions and imbrications? Gore Vidal wrote boring novels. Was that worth doing? Proust, like Gore Vidal and Jack Kirby, lived and died. Was that worth doing? And did anybody do it well?

|

| photo by Egor Gordeev on Unsplash |

8.

The title To Write As If Already Dead might be traced through quotations Zambreno uses:

Guibert: "Someone about to start taking AZT is already dead, beyond the hope of salvation."

Kafka: "I need solitude for my writing, not 'like a hermit' — that wouldn't be enough — but like a dead man."

Blanchot: "At some point the writer — perhaps because of financial constraints or other pressures — pronounces the end and then the artist pursues the unfinished matter elsewhere."

Zambreno: "Another friend writes to me, one who asked me not to name her, well the only reason Guibert wrote what he did is because Foucault was dead and Guibert knew he'd soon be dying, otherwise he would have refrained. You don't know Guibert at all! I want to say."

An editor to Zambreno, rejecting her book: "I'm tired of the conventions of autofiction."

Zambreno: "...in real life I thanked the editor for his thoughts, knowing the power he still held over me, or the power at least that I felt that he held over me, the prestige attached to his name versus mine, the possibility that he could change his mind, or publish me someday, or that if I acted unprofessional by being leaky in any way, that would somehow brand me as difficult in the publishing world, which would then take away my ability to attempt to make a living by piecing together adjunct work and contracts, always renewed every year after I complete my applications, but here, in the space of a work I only know one will read, for it's only one reader reading at a time, or perhaps no one will read, what does it matter, I am already dead, I can say what I'm thinking, and feeling, that I wept in the adjunct office when I got his email, and then had to put on a face for my straight male student who was enthralled by the work of a particular male writer of autofiction published by this same press, I wanted to say, is he so tired when his friend does it so prestigiously, and that I felt this rejection deeply for some time."

Guibert, to an interviewer who asks about his sentences: "They are like escalating fevers, outbursts."

Guibert: "My book is battling the fatigue created by the body's struggles against the attacking virus."

9.

We could go on, but at a certain point Bo Burnham and I both know we must end. Zambreno ends with a vision of having the time and freedom to write the book we have now read, except we haven't read the book she describes, the book written in health and leisure; we have read the book that was possible instead of the book that was dreamed. That is what the pandemic has given us, at least those of us who haven't died from it, it has given us a requirement of the possible rather than the dream. Let your commas splice, let your sentences flow, let your point of view falter, let your ideas jumble up against each other, let it all hang out, let lists linger, let songs play on a loop, let laughter track, let children cry, let friends disappear, let clichés speak their truth, let the camera see the mirror, let the show go on, let the last words be whatever the last words happen to be.

I don't know why you don't believe me, but this really did happen, Zambreno writes. We know, because what really did happen is what we are holding in our hands.

You're really jokin' at a time like this? Burnham sings, ironic and sincere.

Really.

Really?

Really

"What are you saying?" the small boy asked.

"Poetry," she said. She had found that the word "poetry" excused any mental ramblings and he understood. He was supposed to say Jack and Jill went up the hill, out loud. She said it was all poetry, only hers was complicated.

—Bessie Head, A Question of Power