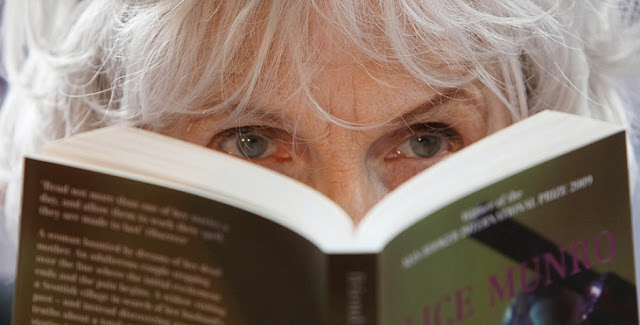

Alice Munro at 90

Today is Alice Munro's 90th birthday, and her singular, extraordinary career deserves great celebration.

Munro's first published story, "The Dimension of Shadow", appeared (under her name at the time, Alice Laidlaw) in the April 1950 issue of the student literary magazine of the University of Western Ontario, Folio. According to Alice Munro: Writing Her Lives by Robert Thacker, she soon began sending her stories to Robert Weaver ("the best friend the Canadian short story ever had"), who ran a radio series on the CBC devoted to Canadian short stories; after rejecting a few, Weaver broadcast a reading of "The Strangers" on October 5, 1951. Weaver encouraged her to keep writing and to submit her work to literary journals. Her first professional appearance in print was with "A Basket of Strawberries" in Mayfair magazine's November 1953 issue. Her first collection, Dance of the Happy Shades, was published in Canada in 1968, in the U.S. in 1973, and the U.K. in 1974. In March 1977, The New Yorker published "Royal Beatings", Munro's first story there; within a few years, she would have a first-reading agreement with the magazine, and the vast majority of her stories from then till now would appear in its pages, making her one of the most prominent short story writers in the English language and the first writer whose career was almost entirely devoted to short fiction to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

I list the dates of Munro's early publications above because from our vantage point now it can feel like her success was inevitable, that Alice Munro has always been ALICE MUNRO. But look at that trajectory — it was fifteen years from "A Basket of Strawberries" to Dance of the Happy Shades, nearly twenty-four years to "Royal Beatings". Munro was an interesting, confident writer from the beginning, and her talent garnered attention — Weaver mentored her right away, and Dance won the 1968 Governor General's Award for English-language Fiction — but it's a long distance from being feted by the (tiny, insular) Canadian literary scene in the late '60s and early '70s to the New Yorker. As with so many writing careers, when we look beyond the public success, we see a long period of hard work, disappointment, obstacles, and, if there is success, luck of timing and circumstance. Munro had the talent, certainly, but she also had the luck to encounter people like Weaver, her eventual agent Virginia Barber, and the young Charles McGrath in his first years as a fiction editor at The New Yorker — people who not only understood and promoted her writing, but gave her the encouragement, guidance, and resources to become the best writer she could become. Crucially, these were people who loved short fiction itself, and who appreciated Munro as a short fiction writer.

For decades, editors and publishers encouraged Munro to write a novel. One of the reasons Dance of the Happy Shades took a while to get published and then even longer to be published outside Canada was the belief then — and now, still — that short story collections don't sell. Writing short stories was what you did on your way to a novel. Short stories are finger exercises, practice for "real" work. Munro tormented herself for years trying to write a novel. Eventually, she came up with The Lives of Girls and Women, which is at least as accurately described as a collection of linked stories as it is a novel. It was published and marketed as a novel because that's what sells, but it is no more (or less) a novel than The Beggar Maid. Munro was inspired in this kind of writing by Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio and, especially, Eudora Welty's The Golden Apples.

It is now a cliché of Munro commentary to say that she writes stories that feel like novels. There is a depth to her writing that this cliché points toward, a refusal of minimalism within the miniature. It is also a cliché now to compare her to Chekhov, but there's a reason that the comparison comes so easily: like Chekhov's mature stories, Munro's tales coax rich implications across a tapestry of individual details. (Think of how Treplev compares his own, inadequate, writing with that of Trigorin in The Sea Gull: "He writes that the neck of a broken bottle lying on the bank glittered in the moonlight, and that the shadows lay black under the mill-wheel. There you have a moonlight night before your eyes, but I speak of the shimmering light, the twinkling stars, the distant sounds of a piano melting into the still and scented air, and the result is abominable.") The commonly-perceived sense of novelism in Munro's stories isn't only because of well-chosen details, however. It is perhaps primarily a result of scope. I think of it with a visual metaphor: Munro gives us pieces of a mural, and those pieces suggest the whole. Though she may write about brief moments, those moments exist within a frame of history. Many of Munro's best stories span multiple generations of life. Along with the scope, though, come shifts of perspective that highlight contradictions and ambiguities. Gaps of recorded history intermingle with the uncertainties of memory and imagination. What the claim that Munro's stories feel like novels seems to me to point to is this extraordinary effect where the story offers not only what is stated but also entire other stories that are implied.

In a 1986 interview with Publisher's Weekly, Munro said:

I no longer feel attracted to the well-made novel. I want to write the story that will zero in and give you intense, but not connected, moments of experience. I guess that's the way I see life. People remake themselves bit by bit and do things they don't understand. The novel has to have a coherence which I don't see any more in the lives around me.

The incoherence of people's lives is one of Munro's great subjects, and her interest in matching that subject to the short story form is what has made her work important to me since I was a teenager and discovered her via the local library's copies of Best American Short Stories, then in college picked up a copy of the Selected Stories that was being remaindered. Reading "Meneseteung" opened up my idea of what short fiction — and all fiction — might do. Shortly after I got the Selected Stories, Munro's next collection appeared, The Love of a Good Woman, and I checked it out from the library as many times as they would let me, until eventually I bought my own copy. For a long time, I read Munro with awe, unable to figure out quite how she achieved her effects. I remember reading "Silence" in Best American Short Stories 2005 and immediately writing to a friend about it because it felt like I couldn't possibly continue with life until I exclaimed over the wonder of what Munro had written. (Luckily, I have indulgent friends who also love to enthuse about Munro's stories.)

Though Munro's uninterest in "the well-made novel" has kept her from being a novelist in any traditional sense, her accomplishment is not only via individual stories. Lives of Girls and Women and The Beggar Maid are marvelous books because of the ways the individual stories add up to a larger narrative, but Munro has also written other story sequences — "Silence" works beautifully on its own, and then gains a different kind of beauty alongside the other "Juliet stories", "Chance" and "Soon"; all three then have yet another kind of beauty within the whole collection Runaway. From the beginning, Munro has been careful in the construction of her books. The texts of the stories in the collections are often different (sometimes radically so) from the versions in magazines, and some stories have waited years or even decades until Munro felt that there was a book they would fit in. Dear Life, which she clearly intended to be the final collection in her lifetime (and has so far been so; Munro announced her retirement many times, so readers learned to be skeptical, but this time she really meant it) ends with a section titled "Finale" and accompanied with a note: "The final four works in this book are not quite stories. They form a separate unit, one that is autobiographical in feeling, though not, sometimes, entirely so in fact. I believe they are the first and last — and the closest — things I have to say about my own life." Munro's fiction has always been strongly autobiographical (even to the point of neighbors being infuriated by her lightly disguised portrayals of them), and so there is a remarkable, complicated resonance at the end of her (apparently) final book thanks to this material which is declared to be autobiographical ("in feeling, though not, sometimes, entirely so in fact" — note the sometimes, not ... entirely; always open to ambiguity, Alice Munro!). It's like a magician ending a show with a revelation of some of the machinery powering the illusions ... while adding another illusion to the revelation.

Because Munro has tended throughout her life to write about the same area of rural Canada, she is often perceived as a writer of naturalistic realism; because she writes short stories, she has sometimes been superficially perceived as a writer of narrow regionalism. While not entirely inaccurate, both ideas are unjust to her oeuvre because they are too limiting. For one thing, Alice Munro has a great sense of melodrama. Her stories may be built on slices of life, but she is not a writer of slice-of-life fiction. She lacks the breathless bombast of Joyce Carol Oates, but her material can be just as lurid. This is something I love about her, and also one reason why the supreme contemporary cinematic artist of melodrama, Pedro Almodóvar, has been drawn to her writing — and, in adapting the Juliet stories into Julieta, gives us a wondrous transmogrification of Munro's vision. "Munro has a prodigious ability for finding terrible things within simple things," Almodóvar has said. Yes! In quite different registers, both Munro and Almodóvar have found forms to express the moments that strong emotion and tragic events explode through life.

Few writers of such prominence have faced as little negative criticism as Alice Munro. Reading reviews of her books gets boring because so few offer much more than, "Alice Munro is amazing!" I agree, and I am not here to say we ought to be writing hit pieces about Munro, but the unanimity of critical praise itself has become an element of her career, one worth more investigation. The only major work of negative criticism I'm aware of is Christian Lorentzen's 2013 essay for the London Review of Books. Though our tastes often differ, Lorentzen is a critic I appreciate, but his essay is, frankly, pretty stupid. I was disappointed when I read it because even though I venerate Munro as highly as I do any writer, I am suspicious of such unvaried reception as her work has gained. Yet Lorentzen not only seems to have no feeling for short fiction as a form, but also admittedly read Munro's work in the worst possible way — "Reading ten of her collections in a row has induced in me not a glow of admiration but a state of mental torpor that spread into the rest of my life. ... ‘You’re reading them the wrong way,’ someone told me." Ya think?! What a hideously inappropriate, useless way to read stories! No wonder Lorentzen finds little to say about them that is either accurate or insightful. Another great Canadian short story writer, Mavis Gallant, said that stories "should not be read one after another, as if they were meant to follow along. Read one. Shut the book. Read something else. Come back later. Stories can wait." Lorentzen's essay is a waste of time.

Even if we admit that Munro is tough to find fault with (something she shares with Chekhov), readers are likely to have preferred books, preferred eras of her writing. Myself, I prefer the middle and later Munro. The books before The Moons of Jupiter contain plenty of good work, and there are individual stories even as early as "Walker Brothers Cowboy" and "Material" that are marvels, but what I really prize in Munro is the complexity of her narrative structures (well explored by Isla Duncan, who is especially good on the differences between Munro's individual collections), the ways she merges stories of history and individual life, the attention she gives to aging and memory, all of which are most present in the later writing.

Which brings us back to the fact that Alice Munro is 90 years old today. Many writers — many people! — diminish as they enter old age. Yet the stories Munro wrote in her 60s, 70s, and 80s are often among the best she ever wrote, because her great interest in time, history, mortality, and memory has only been given more resonance through her experience of long life. Munro's best stories were waiting for her to age her way into them.

And so we readers can be selfishly grateful to Munro for the long life, the dear life, that made her wondrous art possible.