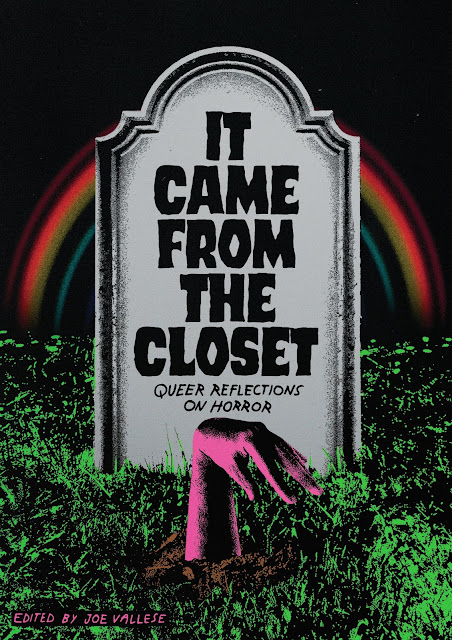

Normality Is Monstrous: On It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror

In the introduction to It Came from the Closet, editor Joe Vallese describes the book as “a collection of eclectic memoirs that use horror as the lens through which the writers consider and reflect upon queer identity, and vice versa.” This is accurate, but not quite specific enough. It Came from the Closet is a collection of twenty-five short personal essays in which queer people remember horror movies that, in many cases, they saw when they were children or young adults—formative years for everyone, but differently formative for people whose sense of self and whose budding desires conflict with those most valorized by society and popular culture. The writers are diverse in identities and backgrounds, and the films that serve as touchstones or anchors for the essays are also varied (within the scope of being horror movies): from Godzilla and Jaws to Get Out and Hereditary to lesser-known movies such as the Cuban psychological thriller ¿Eres tu, papa? (Is That You?) and the Brazilian werewolf movie As boas maneiras (Good Manners).

The best essays in the collection integrate the film discussed with the moments of memoir, inviting resonance and synergy, expanding the possibilities of both the cinematic experience and the lived experience, rather than reducing the film to the size of the individual. Like a good horror movie, the best essays here use surprise as a tool to prompt reflection in us, the audience, about our own response to the material, creating a confluence of text and context, self and other. Horror makes us ask, “Why am I feeling this?” and “Do I want to feel this way?” Queerness does, too.

Part of the challenge of the broad remit Vallese has given the writers is that both queer and horror are mercurial terms, each reaching out with rhizomes of possibility and implication. Tucker Lieberman, in a tour de force essay on trans identity and A Nightmare on Elm Street, writes that queerness itself “is a narrative sitting askew, moving uncannily, resisting taxonomy. It’s not a fixed point in space-time. … The queerest stories are the ones that are hardest to tell.” Lieberman is one of the few writers to bring the difficulty of telling to the form itself, creating a structure of memory, reflection, and analysis that is not forbiddingly avant-garde but nonetheless feels fresh, allowing a balance of memory and ambiguity that suggests at least as much as it states.

Viet Dinh also breaks the bounds of conventional memoiristic writing, in his case by taking Susan Sontag’s structure from “Notes on Camp” and applying it to the notorious 1983 slasher movie Sleepaway Camp. The effect is thrilling, and helps Dinh offer weighty insights into the film, horror, and queerness without the essay itself ever feeling weighted down. The result is an essential piece of writing on a movie that is, on one hand, queerly ahead of its time and, on the other, clearly intended to invite transphobic horror.

What anyone finds horrifying—and why—is a recurring concern in It Came from the Closet. Undoubtedly, the makers of Sleepaway Camp, for instance, expected the big surprise at the end of the movie to disgust, repulse, and horrify viewers because of how the revelation violates gender norms. But, as Dinh shows, queer viewers have always been skilled at reconfiguring the phobic gaze, finding spaces for our selves in the cracks and corners of dominant expectations. We know what it feels like to live under threat, and we know the sense of threat we pose to hegemonic society. Horror movies already sit against the grain of what is considered good and respectable. The more outré, the clearer the distinction with the desires of the powers that be. As Dinh writes, “Slashers … make the victims the transgressors. Consider the oft-stated ‘rules’ for surviving a slasher film: no sex, no drugs, no wandering off alone. What are these rules if not conservative morality? What is the killer if not a brutal enforcer of this morality?” The challenge and power of Sleepaway Camp is that it gives us a killer who is also a victim, a monster made monstrous by a brutal regime of compulsory cisheterosexuality.

Outsider visions serve as cultural reminders that we do not have to accept the terms of use offered by oppressive forces. Writing of 1970s horror movies in Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan, the queer critic Robin Wood said, “The interesting horror films of the period, without a single exception, are characterized by the recognition not only that the monster is the product of normality, but that it is no longer possible to view normality itself as other than monstrous.”

For viewers from marginalized groups, horror movies make society’s values vivid while also offering openings into new conceptions, new structures of feeling. Horror’s power is rarely in its ideas, and horror is less a genre than, as its name makes obvious, a mode of emotion. Because emotion has its own rules and roads, even clear intentions from filmmakers may be ignored or reshaped by spectators. Horror movie fans have long gloried in the slaughter of the author. Viewers cheer the monsters, laugh in the “wrong” places, pull opposite messages from the movie’s moral telegraph wires. Appropriating a story for our own purposes is a traditional queer art. In recent years there have been more queer-friendly horror films than ever before, but we were loving horror even when it wasn’t loving us. We’re here and we can queer.

While many of the essays in It Came from the Closet attest to the power of seeing one’s queer self in the monsters of monster movies, the relationship of queerness to monstrosity is never simple. We all know this, because we know that our monstrosity—our ability to horrify, disgust, and repulse simply by existing—depends on how we are perceived, and by whom. Homophobia and transphobia are, etymologically at least, species of fear. They are fears given sanction by society, culture, religions, families, peers; they are the normal we are supposed to prefer to the monstrous. But what if we don’t? “If there isn’t a supremacist culture to view things through,” Zefyr Lisowski asks in her essay on The Ring and Pet Sematary, “does monstrosity even exist?”

Horror and monsters may inextricably be linked, but horror is more than monsters. Horror is what monstrosity does to us, a contra-dance of fear and desire. “On some level,” S. Trimble writes in an essay here about The Exorcist, “I knew horror wasn’t just about monsters doing bad things. It’s also about doing gender badly. It’s about the threat and the thrill of getting it wrong.” Threat and thrill swirl with desire, and wrongness of desire is the way of the queer.

Wrongness of desire suffuses these memoirs. Many of them focus on first awakenings of that desire, because for most of these writers, horror movies were a youthful pleasure and are forever linked to the terrors and wonders of adolescent feelings. Countless queer texts take readers back to childhood, young adulthood, first stirrings of queer feeling. We are obsessed with our origin stories, our born-again identities, as if by returning to the site of recognition we might heal the trauma of repression, might offer a tale to soothe the woes of the inner child. Richard Scott Larson’s beautiful essay (first published at Electric Literature and reprinted in revised form here), about a difficult childhood and the figure of Halloween’s Michael Myers, is a kind of ur-text for the whole anthology, a threnody for all that was lost, mutilated, disfigured by a reality that allowed little comfort to a child still feeling his way toward self-recognition. Halloween cast a powerful, mysterious spell. Its visual and emotional landscape proved pedagogical: “The film teaches a voyeuristic way of being in the world, a way of looking without being seen. I recall my first furtive glances of other boys in the locker room after gym class and longing for the safety of something like Michael’s mask, the ability to hide a desire that I knew would be made plain by a quick glance in the direction of my gaze.”

Reactionary forces are also obsessed with childhood, attacking both queers and horror movies as dangers to children. The push and pull of valorization/demonization traps horror and queerness in a suspended adolescence, a forever war on the battlefields of innocence, purity, and contamination. Yet horror and queerness also have much to say about the later days of life. (I have found nothing so terrifying as a queer middle age I never anticipated.) Have we stunted ourselves by going gaga over the ways we are born?

Rhetorics of childhood also become rhetorics of authenticity, with the child as father to the man. But what if we don’t care about our childish self, don’t want a father, aren’t a man? Carmen Maria Machado, in an essay on Jennifer’s Body, writes that the “‘born this way’ narrative, while politically expedient, has done untold damage to narratives of the queer experience, implying any number of horrible ideas: that you cannot move toward desire without some generic component urging you to do so, that experimentation is inherently problematic, that you have to know your truest and deepest self to act on something.” Machado’s sharp questioning of orthodoxies is a highlight in a book that could easily have gone in a conformist direction, a danger everything having to do with horror must face, because fear can be a powerful weapon for conformity.

Ours is an excellent era to consider the uses of fear, not only because we are experiencing a renaissance of horror films and writing, but also because ours is a time when forces of reaction, oppression, and outright fascism deploy fear for their own purposes. Horror helps us find the disgust and fear we carry with us, sometimes known and oftentimes to our own surprise, and it helps us recognize those feelings, work with them, wrestling and wrangling the atavisms in our shadows.

In my own experience, horror is as necessary now that I am some decades away from childhood as it was when I was young. With age, you accumulate more ghost stories than origin stories. Since so much queer culture in the U.S. fetishizes youthfulness, it would have been nice to see a wider range of age experience represented in It Came from the Closet, a greater sense of deeper time. (It’s there in some essays, but youthful experience dominates.) But perhaps this book is just the beginning. The richness of the horror genre and the diversity of queer life can only get glimpsed in one collection of twenty-five essays. It is to Vallese’s credit that he found writers who expand our idea of what both queer and horror might mean, and who would all, I expect, argue that an entire shelf of such books might be made, and ought to be. After all, there is a long tradition of great horror movies spawning sequels…