Almost Everything: The Auctioneer by Joan Samson (1975)

If I were preparing to teach a course in fiction writing (something I haven’t done for a few years now), I would be tempted to assign Joan Samson’s 1975 novel The Auctioneer, because it is both not a bad book and also a book with some specific flaws that prevent it from being a great book. These are the most instructive texts.

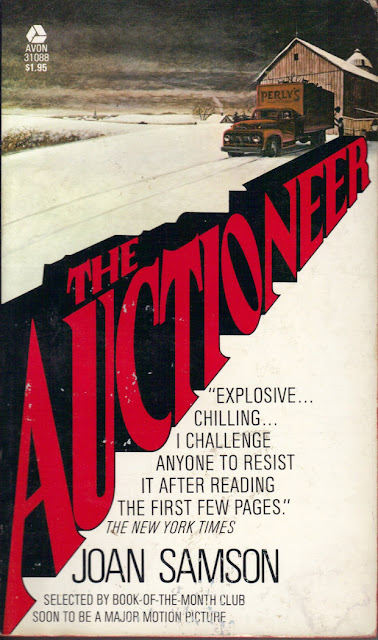

I started reading The Auctioneer with great hopes. For one thing, it is set in central New Hampshire, where I live, a place often ignored by fiction writers. (You might be surprised how few notable works of fiction are set in rural New Hampshire, a place that has attracted plenty of writers to visit or live, but fewer to write about.) It has the reputation of being a lost classic, a book that got good reviews in hardcover, sold about a million copies in paperback, got optioned by Hollywood, and then disappeared, probably because its writer died tragically young of brain cancer, and so a promising career became a single pretty good book. In recent years, it has gained some attention and is back in print via Valancourt Books, who do important work resurrecting otherwise unavailable fiction. (Previously, there was a limited edition hardcover from Centipede Press as well. It has a reputation for being a horror novel, but that's just marketing; at most, as popular fiction labels go, it's a thriller. But not really that, either.)

By the middle of The Auctioneer, I realized this was not quite the masterpiece its reputation suggests. It truly is a tragedy for readers that Samson died so young, because it’s obvious that she had a lot of talent and that talent could have led to significant writing. The Auctioneer is so close to being better than it is that I found myself sometimes infuriated while reading it — one more good pass with the aid of an editor could have bumped the book into true classic status.

The story is a simple one, and that simplicity is unquestionably a strength but also a source for many of the weaknesses. A mysterious auctioneer, Perly Dunsmore, arrives to a rural farming community in New Hampshire and begins holding auctions to raise money for the police department. He gathers items from the local people and sells them to folks from out of town. Soon, there are new police cruisers and new deputies. These deputies help Perly gather items, and the weekly collections become less and less voluntary. Eventually, it becomes clear that Perly has grand ideas for the development of the town, and those ideas do not involve the people who already live there. We see all of this through the eyes of John Moore and his family: his elderly mother, his wife Mim, and his four-year-old daughter Hildie. They have a small farm on the outskirts of town, on land that’s been in the Moore family for many generations. Bit by bit, the family lose everything they have, until eventually John takes things into his own hands. (Sort of.) In the end, much is destroyed but order is restored.

There really isn’t much more to the story than that, but the book is not small — about 80,000 words, I’d guess (300 pages in the Avon paperback from 1977). At half that length, it would have still be able to do what it does; many pages and incidents feel drawn out or unnecessary to me (but I am a person who thinks most novels are too long; a person, in fact, who thinks most movies ought to lose half an hour and most TV series could stand to shed a few episodes per season. It is no wonder I prefer short stories!). The narrative slowly peels away all the material elements of the Moores’ lives, and we see their house and circumstances stripped down bit by excruciating bit. This is excellent for verisimilitude: though the premise might seem shaky if you stop and think about it, the takeover of the town proceeds in little steps that individually feel reasonable.

This slow erosion of reason makes the story work especially well as a parable of fascism. The little bits of life we give up for promises of prosperity and safety accumulate into a maelstrom of conflict and oppression. Having lived through the absurdities of the contemporary political and social landscape, it’s not hard to see the events of The Auctioneer as realistic. The problem is that the trajectory of the first half or even two thirds of the novel is unsurprising. Once the reader understands the premise, all we get to do is watch the pieces fall into place. In a novel that relied less on plot than The Auctioneer does, this would be less of a problem, but we don’t have a lot else to latch on to.

The book’s biggest failure is its characters. Other than John Moore, all of the characters are pretty simple, and most are stereotypes and caricatures. John’s mother is a tough old Yankee, as familiar a type as there is for the region. His wife has some spunk but doesn’t do much with it. His daughter is what most children in thrillers and horror stories are: bait for the reader’s sympathies. The townspeople are little more than names. And Perly Dunsmore, who ought to be a grand villain, is more a cipher; he’s a detestable force for destruction, but isn’t imagined in enough detail to be either compelling or frightening.

All of those weaknesses are common to many works of mediocre popular fiction. It is other weaknesses that make the book worth analyzing.

First and in many ways foremost, the protagonist is a problem. John Moore never really succeeds at doing anything. He is infuriatingly ineffective from start to finish. This is an interesting choice, even if ultimately I thought it fatally weakened the book. Like John’s mother and wife, we can’t help but want him to do something. Thematically, this is interesting: a proud New England farmer who can’t live up to the stereotypical male ideal of action. The thing that drives so many mediocre white guys nuts: their ineffectiveness. That’s good stuff, but it kills a plot unless it is balanced with other elements because it is tedious to read about somebody who dithers, hems and haws, broods. Hamlet the character is insufferable; Hamlet the play is immortal because its other characters, its situations, and more than anything else its language are all fascinating, compelling, bursting with energy and surprise.

Anton Chekhov provides another good comparison. Chekhov’s first successful full-length play, Ivanov, has its moments but is not very good overall. (It’s better than his first, Platonov, but that’s not saying much.) Chekhov, like many Russians of his era, was fascinated by the figure of the “superfluous man”, a figure that in works of fiction and drama, despite the writers’ best attempts, often became the boring and ineffective man, sapping the energy from narrative. Eventually, Chekhov’s genius led him to see that for such a figure to be compelling, it must be surrounded by other figures of different types in a network of situations, actions, and dramatic moments. Uncle Vanya is a vivid example. Vanya as a character is pathetic and fails at pretty much everything. A story with him as the primary source of focus and action would be awful. The beauty and power of the play comes from the web of relationships among the characters, sometimes comic, sometimes tragic, often somewhere in between. The energetic structure of the play’s relationships carries us around the black hole of energy that is Vanya, allowing him to be all that he is without the play sinking to his level. This, paradoxically perhaps, raises Vanya in our eyes. We are able to see him and even sympathize. By the end of a good production of the play, the audience is filled with emotion — the play is a masterpiece because it uses its tremendously flawed characters to help us reflect on their (and our) common humanity.

It is no criticism of Joan Samson to say she wasn’t the writer Chekhov was. But the failure of her conception of John Moore within the novel becomes starkly clear when held up against the bright light of obvious masterpieces like Uncle Vanya and Hamlet. John Moore has to carry too much of the novel’s weight, and our reading isn’t often enlivened by energy from other characters, from language, or from ideas.

In “Digging the Subterranean”, a revelatory chapter of his book The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot, Charles Baxter describes what he calls “congested subtext”: “a complex set of desires and fears that can’t be efficiently described, a pile-up of emotions that resists easy articulation”. John Moore in The Auctioneer almost has enough subtext congested in his character to be compelling, but he’s ultimately just too simple. Baxter also points out that in a serious story (as opposed to a comic story), an obsessive character generally should not be the primary focus; such stories are most effective when the obsessive, maniacal character is observed by a more stable character such as Ishmael in Moby Dick or Nick in The Great Gatsby. Unless the point of the story is to put us in the mind of the obsessive (e.g. Ramsey Campbell’s The Face That Must Die), we as readers need some distance for the sake of analysis. This isn’t exactly the problem for John Moore as a protagonist in The Auctioneer, but it signals the problem: John is a basically stable character without an obsessive/maniacal character to observe. Perly Dinsmore certainly could have been a focus, but that’s not how Samson chose to write her novel. Perly is mostly off stage. We see his effect more than his actions, and the times we do see his actions, they aren’t so much actions as speeches (and usually overlong ones, at that).

Had I been Samson’s editor, I might have challenged her to rewrite the novel, or at least major sections of it, from John’s wife’s point of view. Mim is a mostly undeveloped character, and yet she is more interesting than her husband. She is taken in by Perly’s charms and promises in the beginning, and ends up feeling guilty because of it. That’s an interesting trajectory, far more so than John’s stoic ineffectuality, which hardly changes from beginning to end. The scenes primarily from Mim’s point of view are some of the most engaging in the novel; unlike her husband, she is an active character with hints of depth to her personality.

(Thinking about this, I remembered the recent remake of the movie Candyman. Like The Auctioneer, the new Candyman isn’t bad, but it is kept from being a lot better because of what seems to me a mistaken choice for point of view. The movie’s story is really that of Brianna [Teyonah Parris], not that of Anthony, her boyfriend — and yet until the final scene, the movie is set up as if it is Anthony’s story, and so a lot of emotional resonance gets drained away.)

Because the characters mostly fall flat, The Auctioneer’s thematic exploration of power, money, and corruption fizzles. All the pieces were in place, but they never quite catch fire. To seize the reader’s imagination, the sorts of ideas and concepts we gesture toward with the inadequate word “theme” must be placed with care, integrated into the structure and substance of the whole. Samson almost gets there with the figure of Perly as an autocrat, but needed more attention to the details of his characterization — for instance, she barely returns to a fertile situation she set up where Perly takes over the town’s church and makes himself the preacher. The church is important to a memorable later scene, but the earlier information about Perly and the church isn’t connected enough to feel built upon. His relationship to the church would have been a particularly rich vein to draw on, summoning everything from ideas of New England witch trials to Elmer Gantry. If The Auctioneer were really an exploration of power, as it could have been, we would see a more careful delineation of how Perly’s control of the police, then the church, then the economic forces in the town led to something like an apocalypse. The book still offers a shadow of that, but our attention is always drawn away, the analysis of power in the novel always sketchy.

Or consider the ways the book could have been — and in some ways actually is — a sharp dramatization of what we now call settler colonialism. In New England, the colonial past is always present, celebrated via historical markers, holiday parades, and tourist attractions. The setting of The Auctioneer is a fitting one for exploring ideas of land and property, because this is a place where families have lived a long time on land appropriated by ancestors called pilgrims and pioneers. A thematic concept that is well developed through the book is John Moore’s attachment to “the land”, his sense that the property he lives on and inherited from his parents is the source of his identity and of his past and future success. The land John Moore lives on has been owned by his family for generations — but the question they never really ask themselves is what was the land before they claimed possession of it?

Perly is grotesque in his sense of entitlement and power, but the rhetoric he uses to encourage wealthy people to invest in his development projects is hardly new to him: “Until you’ve pioneered on a piece of land of your own,” he says, “you don’t know what life is. You don’t know the rush of sap in the veins that comes of having roots. You don’t know the sense of power that comes from making your own mark. … Until you’ve taken up an ax and bent your back to marking the wilderness with your own name and labor, you don’t know what it feels like to be a man.” The Moores and Perly agree on this. And what Perly does to the Moores is not so different from what the Moores’ ancestors did a few centuries before to the indigenous people they met. Indeed, though John Moore thinks Perly is destroying the town’s traditions and history, in many ways Perly Dunsmore is the person most faithful to the longer history of the place.

Toward the end of the novel, a bulldozer arrives to clear some of the Moore’s land, land they have not ceded, land they still claim for themselves. Trying to argue with the bulldozer driver, who has been sent out to do his work by all the recognized authorities in town, Mim can only argue that the land is theirs. “Sorry you feel that way,” the man replies. It’s one of the most effective moments in the novel because it so clearly demonstrates a truth: rights and claims mean nothing without power to enforce them. Feelings don’t stop bulldozers.

There is a more predictable, clunky, but nonetheless effective moment where John learns this. He naively thinks he can call up the governor of the state and have him intervene. He gets routed to various secretaries of departments, and eventually back to the police. Nobody can help him. He has no authority on his side but, more witheringly, his lack of power makes his claims sound nonsensical to anyone who hears them. Power possesses and shapes its own reason; the less power you have, the less you can participate in — or even be seen by — the realms power shapes. This is the strongest thematic achievement of the book.

(The theme feels of a piece with the book’s zeitgeist. Especially toward the end of the story, I kept thinking of David Morrell’s 1972 novel First Blood, and to some extent the Sylvester Stallone movie made of it in 1982.)

Samson’s real strength as a writer was her attention to landscape and setting. The little town of Harlowe is more vivid than any of the characters. Samson excelled at bringing alive in our minds the everyday life of a small farm, the changes of seasons, the feeling of wandering through a pasture or walking through the woods. Few novels have captured this particular landscape of New Hampshire as well.

Which returns us to the melancholy fact of Samson’s early death, the loss not only to her friends and family, which is the greatest loss, but also to American literature, because despite its flaws (ones common enough to first novels, and many far-from-first novels), The Auctioneer is compelling, and it brings life and vision to a place that is still surprisingly under-represented in the landscape of fiction.