Calm Weather and the Melancholy Tide

Recently, I got an inexpensive used copy of Twice Twenty-Two, a 1966 book made up of Ray Bradbury's story collections Golden Apples of the Sun (1953) and Medicine for Melancholy (1956) — the collections on either side of The October Country (1955). I've been revisiting Bradbury a bit over the last year or so. Though his stories were important to me when I was young, he's someone I hadn't read with any passion since childhood, thinking he was a writer whose childish spirit must not have much to say to me in adulthood. I was wrong.

It may seem strange to say of someone who is so famous and beloved, but Bradbury is an easy writer to underestimate. We associate him with themes of childhood, with nostalgia, with sentimentality. And there is truth in those associations. But it was an essay by the wonderful horror writer Joel Lane (collected in This Spectacular Darkness) that sent me back to Bradbury and convinced me that Bradbury's obsessive theme is less childhood than loss. Loss is where the sense of nostalgia comes from, and it is the ache of loss that fills the nostalgia in Bradbury's best work with melancholy, not sentimentality.

The cruelty of adulthood is that the simplicity and innocence of childhood can't be returned to. Bradbury felt quite deeply the truth that even if your childhood wasn't particularly happy, it was a simpler and more innocent time of life, a time without adult responsibilities or regrets or ailments, a time when, at the very least, a future remains possible. One of the reasons why Bradbury's science fiction is so affecting — I find The Martian Chronicles almost unbearably sad — is his recognition that the experience of adulthood is the steady erosion of the personal future. On our worst days in particular, that innocence, simplicity, and sense of possibility taunt us with their absence. It is not childhood itself that is at the core of Bradbury's work (though it is of course frequently present); rather, it is the death of childhood that fuels the engines of its meaning.

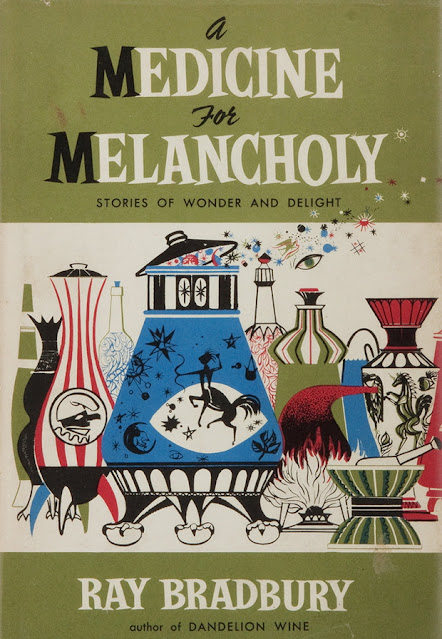

Melancholy is an important word for Bradbury's world, the most common sensation in his best stories. Yet, there is also often wonder. A Medicine for Melancholy is subtitled "Stories of Wonder and Delight". For me, the word delight clangs there. It's too twee. Bradbury certainly had his twee moments, but it's the fusion of melancholy and wonder that makes his work resonate even today.

What I want to talk about here is the first story in the book, "In a Season of Calm Weather", first published in Playboy in 1956. I had read it before, but didn't realize it, because I read it in The Stories of Ray Bradbury, a library book I checked out numerous times when I was young, where it is titled "The Picasso Summer". That was the title of an ill-fated movie starring Albert Finney, loosely based on the story, and for which Bradbury wrote the script. Despite the title change, the stories' texts in the two books are the same. I like "In a Season of Calm Weather" more than "The Picasso Summer", for a variety of reasons, so that's what I'll refer to it as.

The story is short and simple. It is not science fiction, horror, or fantasy, unless we insist that a made-up story in which a famous artist appears as a character is a fantasy. I just call that fiction.

In the story, a husband and wife, George and Alice Smith (note how common, how generic are the names!) travel from the US to southwestern France and bask in the sun. George adores Picasso's art and is excited by a rumor that the famous man himself is in town. One afternoon, as he is wandering along a deserted beach, George sees a man drawing in the sand with a stick. He's having a great time, just drawing away like a child. Of course, it's Picasso. George and Picasso acknowledge each other, Picasso draws a bit more, then leaves. George walks up and down looking at the drawings until it's too dark to see them anymore. At dinner, Alice asks him if anything interesting happened during his walk. He says no. He's distracted. He's listening. He asks Alice if she hears it. Hears what? The tide coming in.

It's a perfect little story in its own way, and there's lots we could talk about — how, for instance, the story is quite matter-of-fact until it comes time to describe the drawings, where Bradbury's language then soars, not in a cubistic way, not trying to imitate in words Picasso's style, but in way that is lyrically excessive, like an orchestra surging, a great swell of passion and (yes!) delight. It's a lyricism that recognizes the impossibility of capturing the reverie of art in words. The mystery of the sublime.

Everything whirled and poised in its own wind and gravity. Now wine was being crushed under the grape-blooded feet of dancing vintners' daughters, now steaming seas gave birth to coin-sheathed monsters while flowered kites strewed scent on blowing clouds ... now ... now ... now...

I don't really know how to imagine "coin-sheathed monsters" or what kites strewing scent on clouds would look like, and we might be tempted to say this is a failure of Bradbury's prose, a tinkly-winkly lyricism more kitsch than art, inappropriate to Picasso, but I think this misses something important: the story is not an objective report of Picasso's art, it is a story of an ordinary American's love of that art. "In a Season of Calm Weather" is not about Picasso; it's about George. It is George's sensibility that is expressed through these words, and I have no trouble feeling my way into George's extraordinary experience through them.

What most impresses and moves me in this story is the way Bradbury uses the structure of a conventional horror story, or of an O. Henry-type twist ending story, for more meaningful purpose. A superficial reading would see this as something akin to a Twilight Zone episode — the last shot could be a pan from George's face out to the waves as we see and hear the water coming in, dooming the art, and then dramatic music rises.

For me, the ending is more resonant than that. Bradbury didn't necessarily need the final scene. We know what happens to things drawn in the sand on beaches. But the ending is a powerful coda because it brings us into George's savoring of the moment, and thus it celebrates the ultimate ephemerality of art — the ultimate ephemerality of all pleasure.

The last line of the story is: "'Just the tide,' he said after a while, sitting there, his eyes still shut. 'Just the tide coming in.'" Importantly, George does not see the tide, he hears it in the distance. There is an action behind this dialogue, implied but not stated: George is imagining the drawings by the artist whose work so moves him, making them real in his mind, and also imagining the water erasing them. In that moment, the art becomes not Picasso's, but his. The drawings live in his mind, as they will live in his memory. He savors this very private moment. He and Picasso are the only ones who saw the drawings, and when they both have died or lost their memories, those drawings will go away as if they never existed at all.

Here we have melancholy, but it is tinged with a sense of wonder and terror at the power of the ocean, the power of time, the way all that we have ever felt or known or valued will slip away. One does not own art, or anything, forever; one can only possess them for a little while. There are no eternal legacies, only some things that erode less quickly than others.

There is, inevitably, a feeling of melancholy to that realization, and Bradbury preserves it beautifully in this story, but there is also within the story a call to different priorities. Too often, we value things like art because of a sense that they will last beyond us, but that is a terrible criterion. Not only is the future unknowable, the future is always a fantasy. It never arrives. By the time we get to the future, it's become the present, and within a blink the present is the past. And then we're dead.

The tide is here, now, always, washing us away.

What "In a Season of Calm Weather" gives us is the experience of both George and Picasso's joys. Those joys are different from each other. For George, it is the pleasure of observing magic, the pleasure of a private show, the pleasure of art. The ephemerality is key to the pleasure. George must savor the moment because he knows there is nothing that can be possessed except in memory, and memory itself is flawed and hazy and eventually dim. George must live in the present at that moment if he is to know the full marvel.

For Picasso, the joy is in creation. It is the childish joy, the joy of making drawings in the sand, drawings nobody is likely to see, no art critics will praise or condemn, no billionaires will add to their Xanadu vaults. The purest art-making, the freest, the oldest and most wonderful. Art made in sand with full knowledge that the tide is due at dusk.

Calming weather.

Let the tide come in.