Dylan at 80

8 fragments for Dylan on his 80th birthday—

1. Oh a false clock tries to tick out my time

While it can feel a bit strange to think of any icon of youth culture (which he surely was in the mid-1960s) as an older person, Dylan has often seemed old, or at least outside of time. He began his professional career not as the rock 'n' roll innovator he would (briefly) become, but as someone devoted to the music of his parents' and grandparents' generation. His debut album only had two original songs (both folksy); all the rest were blues standards or old traditionals. Even when he was electrifying the acoustic world, he never lost his devotion to the old, weird sound. He followed up the rock of Highway 61 Revisited (1965) and Blonde on Blonde (1966) with the antiquarian quiet of John Wesley Harding (1967) and the crooning country of Nashville Skyline (1969). Dylan turning 80 doesn't feel the least bit surprising; it feels appropriate. In many ways, Dylan has always been an old man.

In multiple ways, Dylan seems to exist outside time. Recently, I was struck by something obvious: just how much he accomplished in the first few years of his career. The debut album came out in March 1962, then Freewheelin' in May 1963, The Times They Are a-Changin' in January 1964, Another Side in August 1964, Bringing It All Back Home in March 1965, then Highway 61 that August. And that's just the stuff that was released — there was also the Witmark demos. Most of the songs for which Dylan is best known were released in the first five years of his career. According to Clinton Heylin, between 1962 and 1967, Dylan wrote 207 songs.

2. I and I

Ellen Willis published one of the best things ever written about Dylan in 1967, when her subject was only in his mid-twenties. Even then, Willis identified a core element of what would come to be one of the few defining features of Dylan:

Not since Rimbaud said, "I is another," has an artist been so obsessed with escaping identity. His masks hidden by other masks, Dylan is the celebrity-stalker's ultimate antagonist. ...his refusal to be known is not simply a celebrity's ploy. As his songs become more introspective, the introspections become more impersonal, the confidences of a no-man without past or future. Bob Dylan as identifiable persona has disappeared into his songs. This terrifies his audiences. They could accept a consistent image in lieu of the "real" Bob Dylan, but his progressive self-annihilation cannot be contained in a game of let's pretend. Instead of an image, Dylan has created a magic theater from which his public cannot escape.

Subsequent years showed that Dylan's public could escape the magic theatre; indeed, unless a listener is utterly besotted and completely undiscerning, they will find themselves going in and out of that magic theatre quite a bit — the fundamentalist folkies who hated Dylan's electric guitar and called him a traitor (when he'd only been in the public eye for three or four years!) were simply the first wave of the rest of us. Anybody who accepts Dylan also rejects him. (Even Dylan seemed to reject himself in the mid-1980s). Willis, in fact, wrote one of her last essays about music in October 2001, about Dylan's "Love & Theft", and revealed that she left the magic theatre a lot, finding too much of Dylan lacking in the irony she so cherished when she and he were young.

The question of Dylan and irony is a thorny one. Certainly, his mid-'60s persona was one with a real streak of irony to it — there's a sneer to a lot of his songs then, and even more so to his performances. (By the "Royal Albert Hall" performance of 1966, he was in a tense, antagonistic relationship with his audiences. Albums like John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline, and Self-Portrait can easily be seen as Dylan weeding his audience down to the real devotees.) But after the '60s, there really isn't much irony to him or his work. Instead, Dylan just does his own thing. That's the freedom fame and wealth provided him. And more often than not, his own thing is pretty darn earnest.

See also: I'm Not There.

3. Do you know where I can get rid of these things

For much of his life, Dylan has been a visual artist as well as a singer-songwriter. There is a way in which his albums are like sketchbooks. He works quickly, rarely spending a lot of time in the studio for an album, often to the chagrin of his collaborators and producers. He is famous for the ways his live performances after 1966 vary the songs — consider his lovely rendition of "The Times They Are A-Changin'" for MTV Unplugged, or the never-ending versions of "Tangled Up in Blue". (He even put two different versions of "Forever Young" on Planet Waves in 1974.) With releases like Another Self Portrait, the official Bootleg Series has shown just how much good stuff Dylan discards. This is a guy who didn't bother to put on an album one of his greatest songs — a song that would've been the shining star in anybody else's entire career — "Blind Willie McTell".

Thinking of his songs as sketches explains some of my (and many people's) obsession with Dylan's outtakes, live performances, scraps, bits, jots, remnants. According to iTunes, I have over 2,000 Dylan tracks, a collection I began organizing whenever I first began importing CDs to my computer (probably sometime in 2001, when iTunes was first released). It's an absurd collection, because the majority of it is not top shelf stuff: Dylan's great, but there are only a few albums that anyone could say are entirely excellent, his live performances are notoriously variable in quality, and there's plenty of material that's flat-out awful. And yet this absurd collection is a source of great joy and fascination for me — joy in fascination — because Dylan is just about the most documented musician of all time. Even if you limit yourself to official releases (and few Dylan obsessives do), the Bootleg Series provides an extaordinary view of Dylan's creative process.

This week, I've been listening a lot to Bob Dylan — 1970, an album of outtakes that nobody really expected to get a full release (it was put out there originally just to capture some European copyrights), but which fans were able to pressure the Dylan corporation to make into a regular offering, and I'm glad they did. There's nothing on it that's a great revelation, but it lets us hang out in the studio with Dylan and friends at a relaxed time when they were more or less just playing around. A lot of artists wouldn't want their every blip and boop out there for the world to hear, but Dylan is blasé about it — he's never really seemed to understand why people want this stuff, but he long ago resigned himself to it, and he seems to think that since it's inevitable that this material will find its way out, it might as well be released in the best possible quality (and bring money to the actual producers, rights holders, etc.). Casual fans don't care about this stuff, nor should they, but very few musicians could have so much released and remain interesting to anybody. Yet Dylan's discards have sold well enough to keep the official bootleg series going strong (and to fuel an unofficial bootleg series that feels infinite). Aside from the undeniably high quality of so much of the live material and outtakes, there's something else about Dylan's work that makes the hunger insatiable. Perhaps it goes back to how mercurial Dylan is. Though we know he's unknowable, we still keep trying to know more. It's an asymptotic relationship. Nearly every sound he ever recorded in a studio between 1965 and 1970 is now available, and even though a lot of it is at best repetitive, I still find myself listening to it over and over because this was the time when Dylan tried hard to stop being "Dylan", and what you hear is the sound of genius working against itself, a creature that has built a cocoon and is now trying to emerge into some new, unknown shape. It was a sustained effort, a productive and creative tension, and it's a wonder to hear.

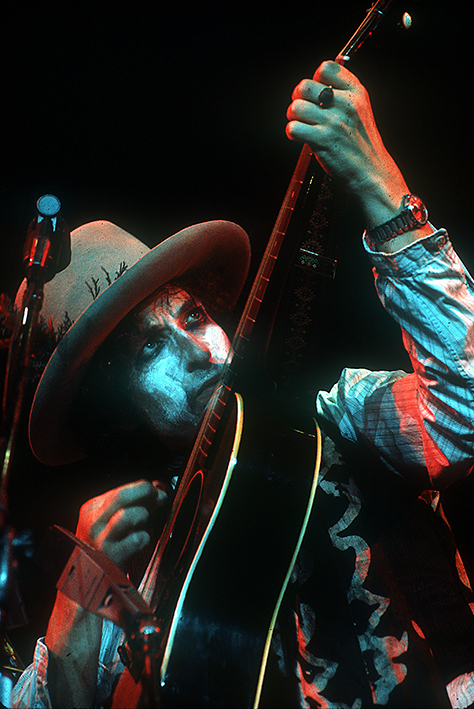

4. I was so much older then

Of course, Dylan didn't emerge into one thing — he refracted, fractalized, fragmented, futzed around — and even uncritical Dylan fans have favorite versions and others they just don't get. For me, Dylan's apex is the fall of 1974 to the spring of 1976. That's when he recorded my favorite of his albums, Blood on the Tracks, and then went on his Rolling Thunder Revue tour. His energy at the time was amazing; his voice was mature and he had excellent control of it; and even though his marriage was falling apart, he surrounded himself with friends and seemed to enjoy the community. Just watch the concert footage in Scorsese's (otherwise pretty shallow and even annoying) Rolling Thunder documentary. In the second half of the tour, the performance get a bit more fierce and ragged, which led to what for me is a marvelous live album, Hard Rain, but I'm very much in a minority feeling that way. The concert came at a time when everybody on the tour seemed exhausted or in a bad mood, and during much of the recording, it was raining, causing instruments to go out of tune and performers to be uncomfortable. The effect is something like a Dylan punk album.

5. Your voice is like a meadowlark

It was probably after Dylan's first concert that somebody said, "I like his lyrics, but ugh, that voice." Or maybe not — as Carl Wilson, in an excellent article on Dylan as a great singer ("or at least vocalist," as Wilson qualifies things) — "when Dylan first came to New York in the early 1960s, it was his voice that people praised. When he played for his folk-singing hero Woody Guthrie in his hospital room in 1961, Guthrie reportedly remarked, 'That boy’s got a voice. Maybe he won’t make it with his writing' (!) 'but he can sing it, he can really sing it.' ... The New York Times writer Robert Shelton, in his liner notes for Dylan’s first album (mostly of covers) in 1962, called him 'one of the most compelling white blues singers ever recorded.'" Soon enough, though, people were slamming Dylan's singing.

I first heard Dylan when I was quite young, via my father's records. I remember finding the voice alienating and my father telling me it was an "acquired taste". I was young enough then to want to do the work to acquire this taste. Weirdly, some of the songs I most liked in my early years of Dylan appreciation were some of his most vocally monotonous. The original recording of "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" became one I listened to endlessly. This is not a song I would recommend to anyone to get them started on Dylan — it's over 7 minutes of something almost like incantation. Maybe what I needed was the simplicity of the presentation. Certainly, it allowed me to wallow in the words, which are among Dylan's most florid. The other song I really loved was "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall", which is similarly long and lacking variety, with a notable richness of language. At the time, I found nothing of interest in Dylan's more musically complex songs, but I also wasn't gravitating toward the beat poetry in spite of the voice, I really found an emotional power in that voice itself, and I also seemed to need the voice not to be in competition with an attractive melody or instrumentation. The only real impediment for me was not the voice but the harmonica. (I still don't care for the harmonica as an instrument, particularly as Dylan plays it.)

Eventually, how Dylan uses his voice became for me part of the fascination.

Carl Wilson created a good Spotify playlist to show the variety of Dylan's singing. It's a good playlist to give to people who say they wouldn't mind Dylan except for his voice. The voice can definitely be a barrier to listeners who want something pretty or conventionally smooth. You do get that with the croonings of Nashville Skyline, but that was a (thankfully) brief experiment. Dylan's habit, especially pronounced on Blonde on Blonde, of elongating a warble into something I think of as the oooooo voice can be tough to get used to — I still struggle a bit with Blonde on Blonde, but the songs are so great that I can get over it, get into the groooooooove of the album. (When people do Dylan parodies, they tend to sound like they're parodying Blonde on Blonde.) But do you really think "Boots of Spanish Leather" is nails on a chalkboard? Or "Buckets of Rain"? Or "Ring Them Bells"?

I'm not sure I really appreciated Dylan as a singer until, in his fifties, his voice lost some range and gained greater gravel. Time Out of Mind was such a revelation that I remember putting the new CD, unheard, into the player, and still remember and my shock at "Love Sick" playing. Voice and song were completely united. The whole album undid me, because up to that point (the fall of 1997, my senior year of college) I really liked Dylan's early albums, but I had not heard anything from the 1970s yet (my father was one of the people who got mad at Dylan for going electric, so his collection stopped at Bringing It All Back Home and Greatest Hits. After my father's death, his collection now mine, I would get Highway 61 Revisited and Blood on the Tracks on vinyl just because I couldn't stand having my father's collection end where it did). I had heard some of Oh Mercy, because it played on the radio and MTV, particularly "Political World" and "Everything Is Broken", and I liked it well enough, but I had unquestioningly absorbed the prevalent idea that Dylan had abandoned politics, betrayed the cause, etc. etc., so I had missed swaths of stuff that would soon become quite important to me. I was then (and still) a huge Tom Waits fan — especially Bone Machine — and to hear Dylan verging into Tom Waits territory was exciting.

It's remarkable to think that Time Out of Mind came out almost 25 years ago now.

Dylan's voice has since lost more range and gained even greater gravel. He can still use it to impressive effect, but for me the rewards seem fewer and fewer. (All those albums of torch songs he did I find pretty much unlistenable.) I can't say I have a lot of enthusiasm for Dylan's recent work, but it's not because of his voice. While there are good songs scattered across all of Dylan's recent albums of original material, he often falls into a rut where song after song has a similarly slow, soporific rhythm. Lots of people seem to like his recent song "Murder Most Foul", but to me it's a weapon against insomnia, nearly 17 minutes of quiet talk-singing with little variation. Similarly, "I Contain Multitudes" has some fun lines, but sounds like somebody singing through closing time at a lounge in Boca Raton. The voice is pretty good; it's the music that makes me snore.

Still, Dylan's voice is really something of a marvel. Everybody covers him, but rare is the cover of a good song that for me really approaches the power of Dylan's own version, if he recorded it well — the best covers are not ones that try to get away from his voice but rather ones that take seriously songs that need to be saved from their original production, which is why the cover album of 1980s Dylan songs is pretty good. But if Dylan did the song justice, it's tough to improve on it. It can be done, though, including by people other than Jimi Hendrix. I adore Dylan's "I Was Young When I Left Home", for instance, but I think Antony and Brucy Dessner make it at least as powerful as Dylan, and Antony & the Johnsons' version of "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" is superior to any version of it I've heard Dylan sing. Antony's extraordinary voice is so far in the opposite direction from Dylan's that it almost makes comparison irrelevant. Similarly, Odetta was one of the great Dylan interpreters because of the vast difference in their vocal instruments.

Catherine Nichols put it well in 2016: "There’s more person in Dylan’s voice than anyone else’s; his voice transmutes the unnerving sensation of being wholly, troublingly alive."

6. A book that no one can write

Regardless of how you feel about Dylan himself as a writer (my thoughts on him winning the Nobel for Literature are here), Dylan as a figure and a musician has led to quite a bit of good writing. Last year, Longreads posted a useful, basic list by Aaron Gilbreath of articles about Dylan. There's plenty more, including Mark Richardson's essay about being a Dylan obsessive when hardly anybody else you know is. ("Yet that actually enhances and deepens my connection to his music. Dylan’s songs, on a fundamental level, are about moving through the world on your own.") and Scott Warmuth's excavation of the echoes and borrowings in Dylan's memoir. Dylan has provoked good negative writing, too — John Leonard, for instance, wrote a fun review of a couple Dylan biographies that is decidedly unimpressed with the guy (and besotted with Baez): "Because Joan Baez loved him a lot, I have to assume that he is not as much of a creep as he so often seems."

For anyone who doesn't want to do a lot of deep diving but is nonetheless curious to see what's been written about Dylan, Studio A: The Bob Dylan Reader is the place to start.

While perhaps primarily for obsessives, Michael Gray's Bob Dylan Encyclopedia is informative, comprehensive, and often a lot of fun to read — it is not a dry, scholarly tome but rather the idiosyncratic product of one (highly informed) man's mind. It includes thoughtful, judicious critical judgments such as this about Planet Waves: "It is demonstrably a Dylan album of the 1970s in managing to bind together elements of the city-surreal-intellectual world from which Blonde on Blonde's language derived, with a new willingness to re-embrace older, folksier, rural strengths." It also includes occasional entries such as "frying an egg on stage, the prospect of", in which Gray muses on a statement by Dylan that people come to see a performer and that performer could be on stage frying an egg. Gray is in favor of Dylan doing this (but there is no evidence, alas, that he ever did. Maybe for his 80th birthday?).

Dylan biographies abound, but because Dylan the man is so clearly less than his music, I prefer other sorts of books (unless the biographies are of a milieu, as one of the books John Leonard writes about, Positively 4th Street, is.) One of my favorites is Elijah Wald's Dylan Goes Electric: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties, which is far more interesting — even thrilling — than its title suggests. Wald is a musician in addition to being a good writer and dogged researcher (his book on Robert Johnson is a must-read for anybody who cares about popular music). Dylan Goes Electric isn't hugely about Dylan, but more about the world of American music in the early 1960s. It's cultural history but also a rumination on what people want from culture and how we use culture. There are all sorts of rumors and myths about Dylan, the Newport Folk Festival, folk vs. rock, etc., and Wald doesn't just dig into the truth or lies behind those myths; he takes on the much harder job of trying to figure out what work the myths do that makes them so attractive and persistent. This is one of the few books about Dylan that I think you can read regardless of whether you care at all about Dylan.

If you do care about Dylan, though, and want to read about him, you'll have to reckon with Greil Marcus. Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus may be more Marcus than you want to read about one topic, but I love this book because it gives us a way to see Marcus's engagement with Dylan's work through time. Marcus's style is jazzy, even oracular, and you shouldn't read him if you just want writing that goes from A to B in a clear line. Marcus goes from X to N by way of sanskrit and moonbeams. Yet there's tons of thought and knowledge behind his art. The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes is also a book I enjoy, in this case not just because of its Dylanology, but even more so because it's about a pre-Dylan soundscape I cherish. (I didn't get much from Marcus's book on "Like a Rolling Stone" when it came out, but I should probably give it another chance.)

And I love The Dylanologists.

7. All the friends I ever had are gone

There are only a few Dylan albums I tend to listen to start to finish as albums, rather than pulling out individual songs (and skipping ones I care less about), with Blood on the Tracks at the top of the list and World Gone Wrong not too far below.

While many Dylan fans like World Gone Wrong well enough, it's rarely listed as a top album, probably because it's just Dylan, a guitar, and a bunch of old songs written by other people. This is a mode of Dylan's that I very much enjoy — I'm fond of his first album, too, as well as World Gone Wrong's immediate predecessor, Good as I Been to You — but World Gone Wrong stands apart for me in its cohesion. There's a depth and resonance to this album that remains mysterious to me, a quality I can't describe but which perhaps results from Dylan's long interest in this material. He doesn't just sing old songs; he absorbs them and then transforms them into something of his own. His approach is typical of blues and folk musicians — for instance, think of how Sam Collins made "Lonesome Road Blues" from at least 2 different songs (you'll hear bits of "In the Pines" in it, a song that itself originated in two songs). Dylan's version of "Delia" is the most powerful I know, built mostly from David Bromberg's version (which builds from Blind Willie McTell's) but with Dylan's adjustment of the refrain to the mournful, "All the friends I ever had are gone."

The album ends with Dylan's version of "Lone Pilgrim", which Doc Watson often performed. Dylan's approach is gentler, less like a preacher leading a congregation in a hymn. For me, it is the most comforting song Dylan has ever recorded.

8. And that’s good enough for now

It's the music that matters.

Here, then, eight songs to listen to (all via YouTube, since that seems to be the easiest access for most readers):

- I Was Young When I Left Home

- Maggie's Farm (Newport 1965)

- Visions of Johanna (live 1966)

- You Ain't Goin' Nowhere

- Tangled Up in Blue (live 1975)

- Blood in My Eyes (video dir. Dave Stewart)

- Thunder on the Mountain

- Forever Young

|

| photo by Ken Regan |