Revisitation: Men on Men 3: Best New Gay Fiction (1990)

(source in parentheses if previously published elsewhere)

The task for future scholars is clear: to incorporate contemporary gay fiction into the long tradition of homosexual literature and culture while recognizing the distinct contributions of today's writers and their place within a rapidly evolving lesbian and gay community.—from the introduction by George Stambolian

It seems to me that as the Men on Men series has 'evolved,' the number of turn-ons per page has decreased dramatically from volume to volume. Not that there isn't food for fantasy here, but where it exists, it is presented in a way that seems almost furtive and apologetic. ... Men on Men 3 suffers from the absence of authors like Robert Glück and Dennis Cooper (from the original Men on Men), who, without subscribing to the very limited mythology of gay male porn, manage explicitly both to acknowledge and to challenge their readers' experience of desire.

I'm not sure it's sex per se that the book needs more of, but rather the energy of writers like Glück and Cooper — writers who see writing as more than the creation of epiphanies. Men on Men 3 feels very much like a book suffocating under the long shadow of the 1980s minimalists of literary fiction who became the darlings of MFA programs, and who, despite the excellent qualities of a lot of the most prominent stories, unfortunately inspired a narrowing of possibility for many acolytes' writing. Men on Men 3 is a book that feels like it is working much too hard to be respectable. Along with "inert", my notes say things like "a pleasant little story", "unremarkable", "spends too much time on things that don't need it and not enough time on what is most compelling", "a slight story", "a touch too undefined", "a rambling memoir-style story", "slight story", "stagey and overlong", "meandering memoir-like story".

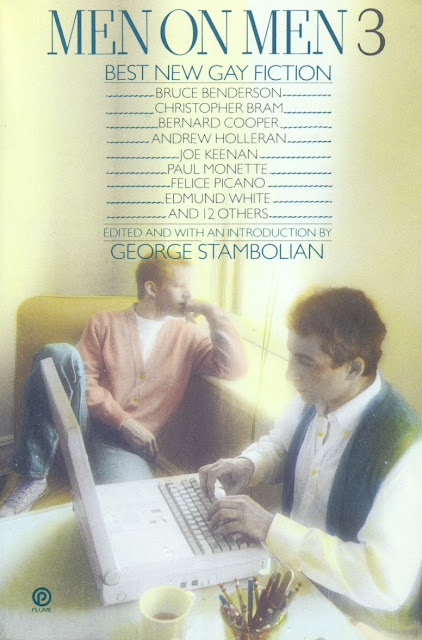

Stambolian wanted to create a moderately big tent in this book, which prevents it from making much of an aesthetic statement: he wanted to show that gay male writers could write in a variety of styles and for a variety of purposes, but that led to the books becoming grab-bags. Yet there were real borders on what he would include. The book's desire for respectability is clear from the limitations of its tent size — Stambolian not only began to distance himself from avant-garde writers after the first volume, but he also did not seek out genre fiction, which in the late 1980s and early 1990s was particularly reviled by the gatekeepers of the literary establishment. Thus, Stambolian kept himself away from two vital alternative sources of prose not subject to the hegemony of Best American Short Story/Iowa Writers Workshop-style writing of the day. (Note, for example, that Conjunctions at this time was publishing Gary Indiana and Kathy Acker in a celebration of "The New Gothic". Another world was possible!) This was a book released by one of the major publishers of the era, and it had a softly pastel cover depicting two utterly unthreatening, inoffensive middle-class white guys. This was a book that you might, if you were lucky, find on the shelves of your local mall's Waldenbooks.

There is great benefit to having such books in the local mall's Waldenbooks — I know from my own experience how important it was to be able to find books with "gay" in their title available outside of big cities. Unfortunately, the quest for respectability led to a quietism of both content and form. In fact, I think it's the formal blandness that is the real failure in these stories. With some exceptions, these are not stories that push themselves very far. They are stories by writers who seem to think that "short story" is synonymous with "minor, trivial".

And while I don't blame the writers or the editor for the social and cultural forces that shaped this book, I do blame them a bit for not believing in the short story as a worthy artform of its own. (It is a problem that continues to this day.)

Nonetheless, there are some stories that ought to be highlighted from this book:

Unlike in previous volumes, one of the best pieces here is a novel excerpt: Henderson's "Myths", a beautifully ethereal and affecting text, one that for the first time in the series offers a Native American point of view. It led me immediately to seek out a copy of the novel it comes from, Native, though I haven't yet had a chance to read it.

Stambolian's own story "In My Father's Car" is quite strong, a father/son story that benefits from a sense of historical depth, of characters with full lives. The father in the story escaped the Armenian genocide and survived the Great Depression and World War II. Stambolian allows this historical context to be clear without it becoming like bad historical fiction or Forrest Gump, where Famous Names and Moments of History overwhelm the ordinary, everyday experience of living through history. There's a certain sentimentality to the ending, particularly the final paragraph, but the story overall is rich enough that it's hardly a fatal flaw.

"Journey" by Martin Palmer verges on being too subtle for its own good, with important elements of the characters and situations a bit too obliquely presented (occasionally, the story feels pointlessly coy), but it's also an effective technique for demonstrating the disconnection, disassociation, and loneliness at the heart of the main character's life. It tells the story of a man who more or less exiled himself to Alaska, and returns to the lower US for his sister and brother-in-law's 40th anniversary. His family are oblivious to his life, ignorant of the friends he has lost to AIDS, and — worse — they show no interest in his life even as he gives them a few clues, a few brief moments to enter an honest, authentic conversation with him. It's pretty devastating, and truly stately in its presentation. The contrast of settings and situations provides real depth to the story. I haven't found much about Palmer except an obituary from 2009 that I expect is the same Martin Palmer, as the bionote in Men on Men 3 says he "lives in Anchorage, Alaska, where he is a practicing physician and an instructor of English", details which align with the obit. The note lists publications in The New York Quarterly, Alaska Quarterly Review, and Gay Sunshine. It also says Palmer "is working on a collection of stories and a collection of poetry", but I haven't yet found evidence that either was published, which is a shame.

"Twilight of the Gods" by Matias Viegener is a weird fantasia of different types of gay male fame all converging with AIDS: Rock Hudson, Michel Foucault, and Roy Cohn meet at a clinic in France and fall variously in love with each other. A few moments feel forced or a bit too on the nose to me, but most of the story is fresh and fun, evoking Donald Barthelme at moments. It's a nice change of pace from all the heavy realism of the rest of the book. I hoped it was part of something longer, but it doesn't appear to be, though Viegener has gone on to create all sorts of writings and art since. I recently read his 2500 Random Things About Me, a kind of social media Oulipean stunt that is alternately interesting and exasperating (both for the reader and, I suspect, the writer as well!). Viegener's connection to the New Narrative writers of the time (Kevin Killian wrote the intro to 2500 Random Things About Me) brings a bit of New Narrative sprightliness to Men on Men 3.

Noel Ryan's "Big Sky" is too diffuse to be powerful, but it's also an interesting portrait of rural queer isolation, telling the story of a troubled, repressed gay man (who may not even identify as gay) with an alcoholic father and violent, hateful mother. Comments on a blog post asking for information about Ryan say that he was born in 1938 and died in November 2015 in Pittsburgh. One comment says that Ryan "was at the Stonewall Riots when he lived in NYC, and he knew Harvey Milk when he lived in San Francisco." His nephew writes that he "was brilliant in many ways and had many demons that he fought throughout his life. Ed graduated from Gonzaga/Carrol College (member of the Gon[z]aga 'college bowl team' if you remember the show from the early 60's) worked for Time magazine, taught English on Cyprus and was truly an expert on anything related to ancient Greece. He wrote through out his life. He was involved with several early gay groups in both NYC and San Francisco. Fortunately, I was able to obtain his papers and writings after his death and will keep those in the family. He loved Montana until the end and his ashes will be spread from slopes of Mt. Helena this summer. He finally will be able to come home."

"Skinned Alive" by Edmund White became the title story of his 1996 short story collection, one of my favorites of his books, though I definitely prefer other stories in the book, including the one from the first Men on Men volume, "An Oracle". Nonetheless, few writers are as captivating when they write with apparent purposelessness, just chronicling the encounters and travels of a few men, as "Skinned Alive" does. The excerpts from one of the character's short stories toward the end of this story are overlong and unnecessary, but White's remains compelling writing, fun to read in the way gossip is fun to get.

This is the first volume to rely primarily on original fiction rather than reprints — the previous volume had 5 stories from Christopher Street and one from The James White Review, the two magazines most devoted to gay male short fiction at the time, while this volume only reprints from a short story collection, an art exhibition catalog, and the VLS. That's quite a change, making the anthology series itself now a major original source for gay fiction more than a chronicler of what was being published elsewhere.

There are 20 stories in this volume, up from the 18 of the previous two volumes. 12 of the stories are in first-person POV, 8 in third-person, the lowest ratio of first-person to third- in the series so far, though first-person still dominates. Sixteen titles are listed in the "Publications of Interest" at the end of the book ("a selective list of journals and magazines that regularly publish gay fiction"), an increase of two from the previous volume's list.

I am eager to read Men on Men 4, because this third book feels so transitional — when, I wonder, will we begin to see the effect of ACT UP (and maybe even the Radical Faeries, Queer Nation, the Lesbian Avengers...)? Will exhaustion become bitterness, nihilism? Will the series grow stifled by the preponderance of middle-class, white gay men and their aesthetics? Can the stories begin to escape the murderous malaise of Reaganism and the 1980s? I will report back when I know...