Gastronomic Gorefests: Fresh and The Feast

By chance, because they're both available on Hulu right now, I treated myself to a double feature of horror movies that both use food, eating, and consumption in entertaining — if repulsive — ways: Fresh, directed by Mimi Cave, and The Feast, directed by Roger Williams.

Fresh is the most fun, The Feast the most satisfying, so I very much enjoyed watching them in that order, with Fresh as a kind of appetizer. (If you prefer some time to digest the richer parts of your meals, you might want to watch The Feast first.) Had I world enough and time, I might have gone for a dessert course of The Exterminating Angel ... or maybe just the Mr. Creosote scene from Monty Python's The Meaning of Life.

Food as fuel for horror is as old as fairy tales and hungry ghosts. As one of the essential elements of life, its deprivation of course leads to anxiety and terror, but there is also plenty of nightmare to be found in the ways food is harvested and consumed. Indeed, food is one of the primary sources of misery and suffering on the planet. Hunger is widespread, despite the world having the resources to end hunger if we chose to distribute food fairly. The production and consumption of meat leads to untold pain and misery for millions — probably billions — of animals each year. Few scenes in horror movies are as revolting as what happens in abbatoirs every day. My diet is primarily vegetarian, but not exclusively. Just last week, I had an excellent hamburger, something I haven't eaten in at least a year, and I thoroughly enjoyed ingesting that finely cooked slice of corpse.

Even the sound of eating is pretty awful. Put a microphone on someone's chewing mouth and the result is far from musical.

And let's not talk about what happens to food once it is digested. There is little difference between a fast food dinner and the world's most sumptuous meal when they're in the toilet.

Thus, food provides all the necessary items and affects of any kind of horror we might imagine: misery, grotesquerie, repulsion...

Both Fresh and The Feast use the harvesting, preparation, and consumption of food to explore themes of oppression and exploitation. Food is a perfect tool for such themes, given how linked it is at every step of its journey to both oppression and exploitation. (Do to humans what we do to animals and you'll be eligible for the death penalty.) Fresh is more a story of individual exploitation and torture, but its background is that of class warfare, conspicuous consumption, and the decadent boredom of, as one character says, "The 1% of the 1%."

(At this point, if you haven't seen Fresh and enjoy surprises in stories, you should stop reading. I'm not going to say a lot about plot details, but it's one of those movies that relies for some surprise on its structure, and that structure is of interest here. The Feast doesn't really depend on surprises, so I think you could read an entire plot summary of that and still enjoy the movie fully, but we live in an age when if you tell anybody that Macbeth dies at the end of the tragedy bearing his name, they'll scream that you didn't provide a spoiler warning.)

I can't think of a film where the title sequence occurs quite so late into the running time as it does in Fresh. It's a delightful, horrifying moment — we've settled in, are enjoying the light romantic tone, the deft dialogue and engaging characters, and even though we know we're watching a horror movie, we're kind of hoping it's not going in the direction that our gut might be telling us it's going. We know you shouldn't go on trips with men you don't know well, but we want to like this guy.

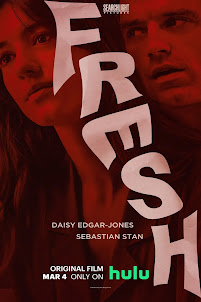

And then ... boom. The title serves as a kind of punctuation. It tells us that this whole first half hour really is what we thought it was: set-up for the nightmare to come. It's a nice variation on a familiar formula. It is typical of horror movies to set up a comforting, idyllic scene and then destroy it. Fresh does exactly that, but takes its time. That confidence is earned by the strong performances from Daisy Edgar-Jones, Sebastian Stan, and Jojo T. Gibbs and the sharp writing by Lauryn Kahn. Though the situations are familiar almost to the point of cliché (which is not a criticism; I think the film needs them to be so), the characters come alive and win our interest quickly. The most important purpose of the first third of the film is to get us to lower our guard, and thus prepare us to feel at least some of the surprise and terror of Noa when she discovers the situation she is actually in.

Despite the gestures of socially relevant themes, I don't think Fresh is doing a whole lot more than offering a highly entertaining take on a captivity narrative, but that's no small feat. Social commentary is seasoning here, not meal, and the film is all the better for it. Unlike many recent horror movies, Fresh is actually interested in its characters and how they relate to each other. As much as I appreciate the film's surprises, what I most appreciated about it was that it keeps Steve alluring. There's a lot to be said about men, violence, and exploitation, but what Fresh understands is that we would escape the problems of violence and patriarchy a whole lot more easily if we were not also enchanted by them.

The Feast is not a subtle movie in its themes, and there isn't much complexity of plot, nor much surprise, because the film is a straightforward working through of fate and punishment for transgression against nature. That's where the pleasure lies, if you can take pleasure from this sort of thing: we pretty quickly know what is going to happen to these weird, terrible rich people, and then we watch it happen. Except perhaps for the very beginning, there was never a moment where I felt that Cadi (Annes Elwy) was in any danger or would fail to execute her design. This was fascinating and gripping. But it's the final shot that convinced me of the film's real value. Look into Cadi's eyes there. See what she sees. Feel the despair, the hopelessness. There are too many rich people to kill; the destruction of the planet is inevitable.

(One of the joys of The Feast has nothing to do with its horror but rather with its words. This is a rare film to have wide international distribution and to be spoken entirely in the Welsh language. What a delight it is to hear!)

Though it is very much a horror movie, The Feast has a certain Yorgos Lanthimos vibe to it. The cinematography by Bjørn Ståle Bratberg is meticulous, often beautiful, even stately. The characters are less characters than amalgamations of weirdness. From early on, we know this is not a realistic film, not verité but rather something closer to allegory, dark fairy tale, nightmarish folktale. Yet it doesn't feel thin or meretricious; quite the opposite. It builds weight and meaning from the precision of its situation and details in the way a short story does, with hints and glimpses of a larger world rather than the accumulations of a novel. This works because the hints and glimpses are, in fact, of something and are not ethereal. Too much modern horror embraces hollow ambiguity; The Feast is not ambiguous so much as it is subtle in how it provides information to the viewer. This subtlety then balances the complete lack of subtlety in the basic storyline as we watch it play out.

Many great horror movies (like great action movies) have proved that the obvious can be a source of great pleasure and that subtlety for its own sake is just a snooze. Figuring out what ought to be obvious and what is better implied is one of the great challenges of creating any story, and it is particularly important with horror stories. It's a question of technique, certainly, but also philosophy. The obvious, simple, and foregrounded material is what the viewer or reader needs to expend the least energy and intellect on. With horror, though, the obvious may be useful for emotional purposes, because while the obvious is not intellectually engaging, it may be exactly what's necessary for a gag reflex. "Too much of a good thing can be ... wonderful," Mae West said, and it's true for horror because the wonderful-horribleness of all that goes over the top can broaden the palette of emotions, sometimes quite complexly: in a work of real achievement, a single image or moment can, for instance, be simultaneously disgusting, hilarious, and rich with pathos.

The Feast is pleasurable in its carefully-composed imagery, its weird characters, its slow but clear and relentless movement toward slaughter, and the base satisfaction of seeing rotten people come to bad ends. In that, it's like a slower, simpler (plot-wise) version of Ready or Not. That final shot, though, calls it all into question for us. It's a true masterstroke, a move Michael Haneke might make, but that comparison returns us to the question of foreground and background, the obvious and the subtle. Haneke's Funny Games in particular is a kind of structural inverse to The Feast: where Haneke wants our complicity as viewers to be foregrounded, The Feast leaves us to wonder about our desires.

Perhaps the best pairing with The Feast is not a horror movie but a book of political philosophy and activism, Andreas Malm's recent How to Blow Up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire. Malm asks why, if climate activists truly believe the world is at stake, activism has been so polite, so scrupulously nonviolent? Where is the Fanonian cleansing violence? John Rapko ends a discussion of the book for The Monthly Review by saying:

Malm’s proposal ... turns on the point that the ruling classes won’t be talked into changing their luxurious fossil fuel consumption, nor a fortiori into dismantling the current economic system and replacing it with another: the violence of destruction of luxury together with its props and symbols is the most likely route to fulfilling something of the aims of the climate movement. Whether Malm’s proposal shall be adopted, and whether it shall be effective, is not something upon which I can speculate; but it’s not clear that those of us who share Malm’s aims have any compelling alternative.

Violence has political dimensions, but it is also a desperate expression of despair. That is what the ending of The Feast shows — the despair, even futility. There is a sense that the massacre in the film accomplishes nothing. The drilling continues, the destruction of the land continues. We have been through this whole ordeal, we have felt great righteous joy in the revenge against awful people, and yet ... what are we left with? That's the question I see in Cadi's eyes at the end.

Moving away from food movies, we might pair The Feast with Clearcut, which I wrote about recently in relation to the idea of folk horror, and The Feast, too, fits into the folk horror rubric pretty easily. Or Spoor, Agnieszka Holland's affecting adaptation of Olga Tocarczuk's Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, which is something of a horror film, though I think it falls a bit short by getting stuck in between character study and allegory in a way The Feast does not.

Both The Feast and Fresh give me some optimism about the future of horror movies because they pair the technical virtuosity of today's film school graduates with real storytelling skills and philosophical awareness. A great meal does not need to be gourmet, and a gourmet meal may not be great — what we as eaters or viewers desire is nourishment and satisfaction. In their own quite different ways, these films provide it.