The Folk Horror Moment

|

| photo by Christian Papaux via Unsplash |

In recent years (and accelerating in the last six months) the term folk horror has become inescapable in discussions of the horror genre generally and horror movies in particular. The release of producer-director Kier-La Janisse's excellent documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched and the astonishing Blu-ray boxed set from Severin Films, All the Haunts Be Ours, accelerated discussion to the point where even people who aren't really into horror feel compelled to offer opinions about folk horror's importance. While I fear this will inevitably lead to over-commodification and dilusion, until the term means nothing other than "creepy stuff with mention of a tree", the present enthusiasm feels truly enthusiastic. There is a there there.

What gets identified as folk horror is speaking to emotions and ideas important to people's experience of now. These emotions and ideas arise from profoundly unsettling fears (related to community, self, identity, and belief) combined with a fascination with — even a yearning for — meaning and transcendence.

I am not here going to delve into definitions of folk horror at any depth or with much patience. There is some value to defining terms, but a lot of discussion gets bogged down in definitions and the policing of borders, achieving very little beyond the planting of stakes in the ground (rather than hearts). Nonetheless, it does help to have some idea of the ways the term has been used. If this discussion is new for you, you can find a good introduction at the Revenant journal.

|

| Witchfinder General |

Horror (Not Horror)

What is most interesting to me about the adoption of the term folk horror is the way it opens up the horror genre. As gets repeatedly pointed out, the term is relatively new and retroactive. This should not be a criticism, since one of the most common ways terms move into discourse is retroactively (film noir was a retroactive term created by French critics after World War Two). The effect is both canonizing and galvanizing. It groups together things which might not have been grouped together before, rendering visible common elements that can then be used in new work seeking to build on the old.

One of the things folk horror does is bring in stories which previously would not have been identified as part of the horror genre. In a traditional sense of genre, horror is pretty narrow. At the most simplistic level, it's monsters, ghosts, and murders; it's stuff that makes the audience scared or anxious. People who write horror stories and make horror movies often push against that narrow definition, but the pushing frequently brings them toward other terms. Horror is no longer horror, it's Strange Stories or it's Weird, etc. Those terms may be more accurate, they may please both creators and scholars, but they don't have the cultural power and ubiquity of horror. As a term, folk horror has probably caught on because it inflects rather than rejects a familiar label, and it does so while bringing more to that label than might otherwise be available, while still being relatively clear in its boundaries.

This has been true from the first films identified as folk horror: Witchfinder General, Blood on Satan's Claw, and The Wicker Man. All three are, in one way or another, concerned with occult ideas in rural places, and they share a bleak tone. Beyond that, they have at least as many differences as similarities.

All the Haunts Be Ours, Severin's Blu-ray set, opens the folk horror label wider than ever before. Even I, someone not much interested in arguing about definitions, had to squint to perceive Ann Turner's Australian film Celia as either folk or horror. And yet it felt at home in this set of films, which is the beauty of what Kier-La Janisse and the folks at Severin have achieved. Even as All the Haunts expands the definition of folk horror toward meaninglessness, nonetheless all of the films feel like they are part of a coherent conversation. Like a number of the other films in the set — most of the best ones, from my point of view — Celia is a character study, a careful exploration of how a community pushes an individual or a small group toward extremes.

|

| Witchhammer |

Communal Demons

A common question in folk horror is: What happens when a community is both powerful and insane? For such purposes, cruelty is a form of insanity, as we see in Celia, where the community is not that of The Wicker Man or even that of the other Australian film it shares a disc with, Alison's Birthday, but the social situation exerting power over Celia is nonetheless cruel, unreasonable, and in thrall to the death drive. Often in folk horror, a community promotes social cohesion through occult and ritualistic means. Again and again, these are stories of groups that torment outsiders so as to strengthen the group. The group may be completely nuts, but it has the power to enforce its idea of reality on its members. This is why sanity/insanity is a useful rubric. To the group, it is the outsiders who are insane. These stories show that sanity is really a matter of who has the power to enforce a particular vision of reality. In that sense, Anton Chekhov's story "Ward No. 6" is a cousin to folk horror.

Witchcraft is among the most common topics in folk horror because the witch embodies the figure of the outsider while simultaneously allowing a consideration of sex and gender. Brunello Rondi's Il Demonio — one of the most powerful films in the Severin set — shows this clearly. Structurally, Il Demonio is surprising because the protagonist, Purif (Daliah Lavi), does not at all conform to a traditional character arc. She starts out troubled from the first scene and only gets worse. At the start of the film, the community has already decided she is too weird and uninhibited, so they have already begun to reject her. We as the audience may be tempted, in the first scenes of the film, to side with the community. Purif seems unhinged, anti-social, annoying. She is furiously obsessed with an unloveable guy, Antonio (Frank Wolff), who shows no interest in her, and we may feel some sympathy for Antonio at the beginning, because here is this vociferous, clingy woman chasing him everywhere. The genius of the film, though, is that it sets us up to stand outside Purif's experiences, to judge her, to indulge our less compassionate (and more misogynistic) tendencies, then slowly, moment by moment and scene by scene, shifts to bring us into her perceptions. The community that persecutes her is cold-hearted, prejudiced, smothered by superstition, intolerant, murderous. Purif needs help and compassion; they give her abuse. We know what makes her into the person of the final scenes of the film, but on reflection we must ask ourselves what kind of torments must she have suffered before the first scenes to make her into the woman we first meet. There is not much of a character arc for Purif, but there is an arc for the viewer's experience of her world. If we reflect on that journey, we may find ourselves doing the good work of questioning why and how we judge who is a monster and who is not.

Il Demonio dramatizes heterosexual men's fear of their own desire, a fear that they then project on the women who inspire their feelings, thus justifying for themselves the abuses they commit. Men desire Purif to the point of raping her, and so she must be a witch, because they, in their minds, are otherwise good and well-balanced people. Folk horror is an especially powerful form for exploring questions of how we construct ideas of ourselves as good people and of our society as one worth upholding.

Witchhammer is a very different film from Il Demonio, but demonstrates another approach to portraying community dynamics — particularly the corrupting effect of power and authority on individuals and moral panics on social groups. For the most part, it is a historical drama in the vein of The Crucible or Carl Theodor Dreyer's great Day of Wrath. A few powerful and discomforting scenes of torture led Witchhammer sometimes to be marketed as a horror film, but viewers who went to it expecting exploitation, or even just something close to Witchfinder General, were disappointed. (This is a slight against the marketing, not the movie. It may be the most technically and thematically accomplished of all the films in the Severin set, truly a major work of world cinema.)

Witchhammer is a portrait of a community, the town of Velké Losiny in North Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), where the witchfinder Jindřich František Boblig sentences dozens of people to death. Director Otakar Vávra had a passion for accurate historical detail, and many of the scenes were filmed not only in Velké Losiny, but in the actual locations where the characters lived and where they were tried and executed. There is no single protagonist, and the characters' individual qualities within the communal structure are not a primary concern (as in, say, a Robert Altman movie); rather, it is the social, psychological, and political forces in the community that propel the narrative: the forces leading to and from the witch trials. The characters serve as embodiments of and victims to those forces.

For all their differences of plot and aesthetics, witchfinder stories usually portray communities in the same way: as places of fear and ignorance where people are easily manipulated by ambitious evil into enforcing conformity with lethal zeal. Stories of good and noble witchfinders or monster killers (such as Dr. van Helsing in Dracula) tend to focus less on community and more on individuals or, at most, families. The witches (or vampires, ghosts, etc.) they find turn out to be real, unlike the witches of Day of Wrath, The Crucible, Witchfinder General, Witchhammer, Mark of the Devil, and such.

An interesting variation — one that may exist, but which I am not aware of — would be a story of a community protecting its good and very real witches against evil outsiders. (It's possible to read The Wicker Man as being something like that, though I think you do have to work against the movie's own ideological force to get there.) Or, alternately, imagine a story of people who believe themselves to be persecuted witches but who are, in fact, neither endowed with supernatural power nor persecuted.

Such stories go against the grain of popular culture, where witchcraft and occultism of all sorts always provide real power (even if only ambiguously) unless it's a story of community oppression, in which case the power either needs to be a imaginary so that the community can be shown to be deluded by superstition, or the power is latent and explodes only at the climax (cf. Carrie). Even something like the tv show The Mentalist, where the premise is that the title character was a con artist who cheated people into believing he had psychic powers before he found a conscience and the police, can't get beyond teasing viewers with "maybe it's real..." An episode where the plot revolves around a psychic has to leave the question of that psychic's abilities open at the end. Because of course it does. Regardless of one's own skepticism, such plots are painfully predictable because that's the way they always go. Occultism is closely woven into the fabric of human history, ancient and modern — indeed, I think that in addition to the influence of Marx and Freud, modern sensibility must be seen as shaped by (and against) Madame Blavatsky — but there are too few stories of occultism as a practice that doesn't need to be seen as true and real to be seen as important and worthy of study. That's the direction some academic study of occultism has moved in recent decades, leading to provocative work, but the world of fiction hasn't caught up, and so we are stuck with the same sorts of narrative developments we've had ever since our ghosts were corporeal beings scribbling away in garrets lit by candlelight.

|

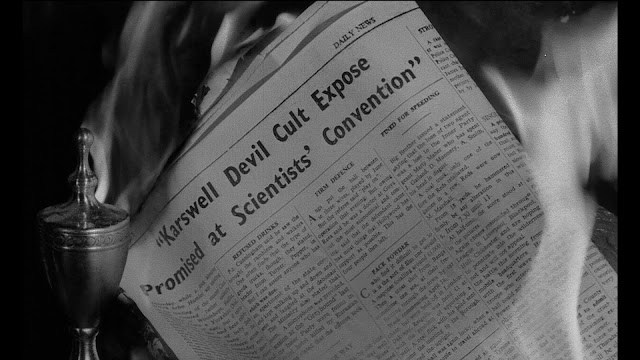

| Night of the Demon |

Occulting

The rich history of occultism has long provided material for horror stories, and even though such stories may feel played out now, there is a need for new approaches. The occult isn't going anywhere, and folk horror offers a particularly clear lens through which to explore it.

Questions of meaning and knowledge arise throughout folk horror stories. Are the old ways better than the new? Was something lost in the past that ought to be revived? Might more fulfilling spiritual paths exist than those of dominant institutions? What secret knowledge do outsiders possess? It is no surprise that such stories should be popular in the last few years, as we continue to suffer through a global pandemic, climate change, social unrest, political turmoil... "The Second Coming" by that old occultist Yeats is overquoted to the point of cliché, but its first stanza sure feels contemporary:

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Meanwhile, people seem to be yearning for something more than what institutions offer, whether those institutions be churches or universities. Folk horror isn't the only thing having a moment; occultism is, too, and has been at least since Trump was elected. In 2019, Tara Isabella Burton wrote about "The Rise of Progressive Occultism" for The American Interest:

As an aesthetic, as a spiritual practice, and as a communal ideology, contemporary millennial “witch culture” defines itself as the cosmic counterbalance to Trumpian evangelicalism. It’s at once progressive and transgressive, using the language of the chaotic, the spiritually dangerous, and (at times) the diabolical to chip at the edifices of what it sees as a white, patriarchal Christianity that has become a de facto state religion.

All sorts of books, podcasts, YouTube channels, etc. offer various sorts of occultism to people seeking something more from the universe than mute, dead matter. (My own favorite is Conner Habib's podcast Against Everyone, which is just so cheerily batshit nutty that I find myself capable of suspending my [considerable] disbelief as I listen to the most woo-woo of woo-woo discussions.) Academic writing on occult subjects is in something of a golden age, perhaps because it's no longer a fast way to end your career by taking outsider beliefs seriously as history, sociology, philosophy, religion — I've been working off and on for a year or so on both creative and academic projects having a bit to do with occultism, so find myself with some recent favorites: Cursed Britain by Thomas Waters; Witchfinders by Malcolm Gaskill; Satanic Feminism: Lucifer as the Liberator of Woman in Nineteenth-century Culture by Per Faxneld; A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion by Catherine L. Albanese; Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull by Barbara Goldsmith; The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern by Alex Owen; Grimoires: A History of Magic Books by Owen Davies; Paranormal America: Ghost Encounters, UFO Sightings, Bigfoot Hunts, and Other Curiosities in Religion and Culture by Christopher D. Bader, Joseph O. Baker, and F. Carson Mencken; The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences by Jason Ānanda Josephson Storm...

The world is chaos, and only ever more chaotic. Even committed skeptics may find pleasure in stories of occult forces, because whether you believe in such forces literally or not, as a structure of metaphors, the occult resonates. There are reasons it holds on and those reasons are not the ones professional scolds like Richard Dawkins and Stephen Pinker will give you. Rationalism is good for many things, but it provides only limited sustenance to generous and yearning minds.

Folk horror as a phenomenon converges with the (always recurring) popularity of occultism and fits comfortably into the space opened up by the rise of "elevated horror" — indeed, we might even trace the popularity of folk horror to the popularity of The Witch, Hereditary, Midsommar, etc. However, it would be a terrible shame to limit folk horror to those sorts of films. Folk horror is not just well-funded film school exercises, it's also The Lords of Salem.

|

| Clearcut |

Into the Imperial Id

And folk horror is Clearcut, one of the best films in the Severin set, a film not normally brought into the horror fold — IMDB labels it with the tags "drama", "thriller", and "western". It's a thriller, certainly, and has plenty of drama, but it's more folk horror than it is western. The folk horror label helps us see the film in a new way, giving more priority to what Clearcut depicts of history, community, and belief rather than just its plot, which otherwise can too easily be seen as a good vs. evil tale of corporate greed. It's not a film that easily offers a good or an evil, at least not in the characters. None of them are good enough and most of them are at least momentarily or inadvertently evil. It's a movie that might feel desperate in its violence — it is desperate in its violence — but by using the folk horror lens to see into deep and communal history, the film reveals tragic depths. At the end, there is an opportunity for something like grace, but the film leaves that to the viewer. This is the great power of ambiguity in horror, a power only available when the horror is rooted in a vision that goes beyond the events depicted and aesthetics at hand. Much gets resolved at the end of Clearcut, but what matters is left open, and that opening is not only about the characters and plot, it is about us as the viewers. We are left to imagine what we want to feel about these characters and their fates, and left to reflect on why we feel that way, why we want what we want from this story. That opportunity for reflection is the key to the film's ethics — and its horror.

There is a brief section in Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched that has resonated with many viewers, a section wherein the postcolonial and anticolonial visions of folk horror are discussed, including an excellent note about the Kingly trope of the "Indian burial ground" that curses unwary people — on the one hand, there's no such thing, because there are various sorts of burial grounds for various indigenous nations; on the other hand, as brilliantly said by Jesse Wente in the film, "If non-indigenous people are going to be afraid of the Indian burial ground, then I've got some news for you. It's all an Indian burial ground."

Clearcut also helps us understand why our moment is a folk horror moment. It has to do with history and what won't stay buried. There's brief mention in Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched of Candyman as folk horror, and this seems exactly right to me. Much folk horror is a type of rural horror, but it's something of a Venn diagram, not a perfect overlap — some rural horror isn't really folk horror (one of my favorite horror movies of the last decade or so, The Eyes of My Mother, is rural, but so disconnected from either community or ritual that I don't see it as folk horror), while there's no reason that horror stories centering tradition, history, ritual, etc. need to be limited to a rural milieu. Candyman is a perfect example.

The long nightmare of racism in the U.S. stands as an abiding horror story, one lived through multiple generations of millions of people. If witchcraft is a central topic of folk horror, there's no reason racecraft should be left out. American history is a horror story. As a death-drive nation, there's lots of repressed to return to. Along with its sequels, Candyman stands as one model for depicting and working through some of that story. That the setting is urban makes total sense, because old demons always want to find new structures to possess, new forests to haunt. Concrete and metal are just as susceptible to old evil as wood and stone. The alchemy of human construction produces horrors of its own. (In that way, Candyman is connected to the Australian film Kadaicha, included in the Severin set, wherein a housing development built on sacred Aboriginal land leads to haunting.) Neither repression nor oppression can erase the past, they can only defer it.

As the United States continues to fight over the American past, few modes feel as contemporary and meaningful as folk horror. Partly, this is because so much of the U.S. self-conception is a folktale, a tale of benevolent Founding Fathers who created a sacred Constitution and set forth a great Experiment in Freedom that continues to this day in the land of the free and the home of the brave. The soil of that folktale sits wet with blood. It's all Indian burial ground — and it's all slave plantation, too. It's all exclusion acts and espionage acts, demonic anti-communism mixing with the dark arts of imperialism, with the grand duke of individualistic capitalism as Lord High Executioner. In America, we make human sacrifices every day.

The excavation of hidden forces and historical secrets in so much folk horror links it to the paranoid thrillers popular in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s (e.g. The Parallax View): there's something happening here, and what it is ain't exactly clear ... but there's definitely a conspiracy of some kind, a secret group pulling the strings, a reality beneath the apparent reality. Paranoia of one sort of another always tends toward the occult, which is no surprise etymologically, as the OED tells us that the word occult comes from the classical Latin occultus, meaning "secret, hidden from the understanding, hidden, concealed". But as we know, the paranoia of the oppressed is entirely justified. They really are out to get you.

The anti-colonial movies in the Severin set are, by virtue of their eras, mostly centered on white folks, but they are not white savior movies — there may be wannabe white saviors in them (Clearcut's protagonist certainly is), but the community-focused nature of the folk horror mode allows a context unavailable in stories more beholden to "a main character we can root for" (the thing so many executives and agents insist on). There's a Brechtian virtue to horror itself: horror is an alienation effect, and that effect allows insights into forces beyond the individual. Often in horror stories, and especially in folk horror, protagonists serve more as a focal point for experience than as a well of sympathy, and sympathy itself becomes a philosophical problem for the viewer or reader. This is good! Especially for those of us whose taxes fund massive militaries and abusive police forces and oligarchic billionaires, those of us whose lifestyles eat up a far larger portion of the planet's resources than do other people's, those of us hastening apocalypse with every purchase — we should be confronted with art that messes with our understanding of empathy, sympathy, and interconnection.

Horror can often do this even accidentally. As Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched points out, both Kadaicha and The Dreaming came out in the year of Australia's bicentennial, an imperial celebration of conquest. Neither movie is especially innovative, and there wasn't a grand plan to issue some horror movies about the repressed colonial past during the bicentennial, but horror is a genre where the whole modus operandi is to rummage around in the unconscious, digging out what brings discomfort, terror, fear, repulsion. And no subgenre is as focused on the collective unconscious as folk horror.

|

Screens

While folk horror has a long literary lineage — everything from the Malleus Maleficarum and other chronicles of witches and occultism to fiction by M.R. James, Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, Shirley Jackson, and on up to numerous recent works and, now, anthologies aimed at the folk horror reader (and even a publisher, Wyrd Harvest Press, devoted specifically to folk horror itself) — its greatest foothold seems to be in the realm of cinema. Perhaps this is to be expected, since the term originated in discussions of film. Movies and tv are mass culture in a way books and, especially, short stories are not, with even little-known niche cult movies reaching more people than all but the bestselling of bestseller fiction. The difference in audience size between a successful movie or tv show and a successful novel is an order of magnitude.

I wonder, though, if the yearning for the distinction that the term folk horror allows might be specifically cinematic. From its earliest days, commercial cinema has been structured by genre; there is no comparable category of media to the "Fiction" section of a bookstore. Instead, there are dramas and comedies and documentaries and sitcoms and westerns and romcoms and art films and news shows and reality tv — and horror movies. As streaming media more and more tries to provide individual recommendations, we see services like Netflix creating super-specific categories (Dark Scandinavian Comedies with a Strong Female Lead; Uplifting Sad Stories for Flag Day; TV Shows for Conservative Vegans Curious about Polyamory and Guns). Folk horror may sit somewhere between these poles. It allows an inflection of a major genre without the specificity of individualized genrefication.

The term may also be more useful with film and tv than with books and short stories because screen horror has been more narrow in its range than textual horror. Novels and short stories are limited more by imagination than budget. Certainly, the budgets of publishers are limiting, and the priorities of publishers have a determining effect on what we get to read, but it's not the same kind of limitation that budgets have on movies and shows. We get countless slasher movies, found footage movies, zombie movies, etc. because they make respectable money (often on very small budgets, so even a movie like The Lighthouse can offer a small return on investment). Folk horror may now enter that territory more deliberately, as producers chase the profitable synergy that genre provides, with viewers seeking out a category that they like, even if they know nothing of what they have bought a ticket to see.

With luck, the future of folk horror is not just interchangeable stories of weird stuff in the woods. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given my own interests and identity, I think the best way forward is to openly bring certain subtexts to the text and, shall we say, queer the witch.

|

| Penda's Fen |

Folk as Queer

I have trouble thinking of a horror story that can't be read as queer, which is perhaps why it has been the genre I have returned to most frequently since childhood. Most horror stories may have been created by cishet folks, often without a queer thought in their conscious minds, but because of their focus on monsters, outsiders, stifling traditions, and murderous conformity, horror stories remain open to queer reading in ways many other stories do not. In addition to being a genre always already queer (if you read it right), not-so-hidden queer horror fills books and movies.

What's surprising, though, is that there aren't more overtly queer works of folk horror. You can find whiffs of queerness throughout All the Haunts Be Ours, but it doesn't really rise to the surface anywhere except in Penda's Fen, a visionary tale of a young man awakening to the world. Like the adolescent it portrays, Penda's Fen is weird and awkward, utterly earnest and sometimes unintentionally silly. I would never claim masterpiece status for it, and you really have to squint to see it as a horror story, but I love it still — it's truly one of my favorite films in the set, even as there are many others better made, less didactic, more focused. Remove what is gawky in Penda's Fen and you remove its heart. (This is a queer value: be your gawky self, because that is what is loveable.)

Most queer horror ends up being about monsters. Every queer person knows what it feels like to create revulsion just by existing. Having been seen so often as monstrous, we embrace the monster figure. We know, too, what it feels like for sex to be associated with death, destruction, misery. One critique of slasher movies is that they are conservative because they punish people for having sex. On a narrative level this is basically true, but that aligns the killer with the conservative mores. The killers that attack horny teenagers are living out the violent fantasies of prudes. (For a fully Freudian take on this, read Robin Wood. For a feminist view, of course, we have to start with Carol Clover.)

For a queer viewer, though, what the rampant heterosex of slashers provides is an alienation of sexuality that feels quite familiar. Richard Scott Larson gets at this beautifully in writing about being young, queer, and obsessed with Halloween:

Watching Halloween was the first time that I knowingly witnessed a blatant representation of human sexuality — in this case, heterosexual human sexuality, the kind of buzzing horniness most explicit in representations of adolescence on film and television — and what I saw confirmed to me that I was not welcome there. ... The experience of adolescence as a closeted queer boy is one of constantly attempting to imitate the expression of a desire that you do not feel. Identification with a bogeyman, then, shouldn’t be so surprising when you imagine the bogeyman as unfit for society, his true nature having been rejected and deemed horrific.

Queers and monster stories have a long history. But why not queer folk horror? So many stories of growing up queer in a rural place are potentially queer folk horror — all sorts of sentences in A Boy's Own Story could easily be transposed into a tale of magick or witches. The emotional landscape of folk horror is, more often than not, congruent with the emotional landscape of queer fiction.

Here, perhaps, is the future of folk horror. As the term gets more currency and lets repetition rob it of meaning, we might keep it fresh by approaching it from a queer perspective. Thoughtful, openly queer folk horror has plenty of new stories to tell.

|

| Impetigore |

Coda

Quick notes on a few films in All the Haunts Be Ours and also in the streaming service Shudder's recent folk horror collection, which includes many (not all) of the films in Severin's set plus quite a few others:

Eyes of Fire: Severin pulled out all the stops to get this restored and released for the first time on DVD, Blu-ray, and streaming. I don't entirely share the enthusiasm for it, because to me it feels kind of like a community theatre production of The Crucible meets Aguirre, the Wrath of God, but there's no denying the visual power of the film in the first 45 minutes or so, and some of the acting is solid. The ending is ridiculous and the actor playing the mad preacher lacks the charisma to make the role do what it needs in the film, but there is nonetheless powerful stuff here and there, and the restoration is beautiful. It's a good example, too, of how folk horror wrestles with America's brutal history.

"Backwoods": A 15-minute short adapting Lovecraft's story "The Picture in the House". It's nicely done. A lot of the shorts in the set are really worth checking out, with this and "The Pledge" being the ones I most appreciated. "The Sermon" is a short that is also queer folk horror.

Leptirica: There's a vampire in the flour mill! Folk horror that also feels like a folktale. Slight, but good fun.

Tilbury: A lot of things that get labeled as "weird" don't seem to be very weird to me. Tilbury is truly weird. I keep writing words here and deleting them because it is so difficult to describe. (Butter has never been more repulsive or horrifying!) It's a gnome/troll story unlike any I've ever seen before. It's funny, sad, unsettling, gross. A gem, really.

Alison's Birthday: A film saved by some strong performances by its lead actors. Otherwise, it seems pretty weak to me, and a good example of the challenges of setting folk horror in the present, particularly in suburbia. Suburbia is itself so terrifying that it drains many folk horror elements of their horror and leaves them seeming quaint.

Wilczyca is an interesting case of a film that has some subversive possibilities if read against the grain. The narrative itself is deeply misogynistic — a strong man is tormented by terrible women. But the strong man isn't especially sympathetic, while the women are a bit more interesting, so while they are portrayed as shrewish, conniving, and evil ... as a viewer, I want to go off with them, not with boring macho military guy beholden to some simpering failed revolutionaries.

Lokis: A Manuscript of Professor Wittembach is a beautiful gothic film, one of the highlights of the Severin set. Gothic and folk horror can be quite different (gothic often avoids community, which is so important to a lot of folk horror), but here the strengths of each mode is on full display in a tale of a scholar and a were-bear that takes both quite seriously.

Dark Waters: The 50-minute featurette on the Severin disk that accompanies Dark Waters is at least as much fun as the film itself, because the cast and crew had no idea what they had gotten themselves into by going to Odessa to film. The movie's certainly worth seeing, with some nice visuals and sharp editing that contributes to the overall feeling of disquiet and confusion. The characters don't make a lot of sense of have much personality, but that's pretty common in horror movies, and there's enough else here to hold attention for at least one viewing, certainly.

A Field in England: I used to think people saying they liked this movie were pranking the rest of us, like saying that watching paint dry is really a great spiritual experience. I thought maybe Ben Wheatley and his collaborators were trying to see what they could get people to take seriously, and that they had succeeded at foisting the most pointless movie ever made off on an audience that just wanted to believe. But then I watched it again as I was going through the Severin set and I really enjoyed the movie. Perhaps I needed the context of folk horror to have an entry to it. I don't think there's a lot of substance to the film, but it succeeds at creating and sustaining a mood, making the events feel more substantial than they have any right to. And it just looks beautiful. God and Baphomet help me, I plan to watch it again.

Kill List: Shudder has included Ben Wheatley's first feature film in their folk horror collection, and it fits beautifully. I get such a kick out of how this movie moves from gangsters to the occult. People tend to either love or hate the ending, and I am among the lovers, because for me it opens it out into all sorts of possibilities, so it doesn't feel (as some think) tacked on or undeveloped. I can certainly see why some people groan at where the movie ends up, but for me it's perfect in its disjunction.

Anchoress: Another historically-based film about witchcraft and persecution, Anchoress is a little bit different from Witchfinder General, Il Demonio, Witchhammer, etc. in exploring other aspects of religion (and religiosity) than primarily the witch hunting. It's a slow, strange movie about various sorts of ferocious belief, barely horror, really, but sits in interesting conversation with Witchhammer and Il Demonio — together, they have much to say about power, gender, religion, community, and history. They each do interesting things with black and white cinematography, as well.

"The Pledge": A short film based on a story by Lord Dunsany, this feels a bit thin, but it's worth watching for some startling visuals.

A Dark Song: I love this movie, but though Shudder includes it in their folk horror collection, I have trouble considering A Dark Song folk horror. It's a character study of two damaged people who lock themselves in a house and perform a long occult ritual. The ritual is one from the Golden Dawn tradition, which feels a bit different to me from folk tradition. (For more on the ritual, see John Coulthart's blog post about the film.) For a while, I found the ending of the movie a bit annoying (actually, infuriating), but now I only dislike a very brief scene just before the final one, a shot of an occult being that still seems to me too literal in how it represents the effect of the ritual. Folk horror or not, this remains one of the most interesting horror movies of recent decades.

Pyewacket: When I wrote about Pyewacket after first seeing it a few years ago, I said it was a "perfect work of occult horror. Not at all original, but it doesn't really matter, because what Pyewacket does, it does with precision, balance, and commitment." That still seems true to me. I also think it, unlike A Dark Song, really is both occult and folk horror, providing a nice bridge between those two types of storytelling.

Jug Face: What sets Jug Face apart from so many other horror movies is its attention both to character and community. Usually, you get one or the other (or, at least as often, neither). This is a story about specific people in a specific place living out specific traditions. In some ways, the horror comes from an unfortunate voyeurism toward rural poor folks, but the film works hard to counteract this to whatever extent it can through specificity.

Wake Wood: Solid folk horror in which excellent actors do heroic work to make characters who seem to get more and more stupid with every passing minute seem believable. It almost works.

La Llorona: A powerful film that nonetheless left me unsatisfied because, as I said when I wrote about it at Letterboxd, it uses the tools of horror to make us feel better about terrible reality. I don't think we should feel better, and I don't think we should fool ourselves into thinking that the terrible people of the world will be punished for their terribleness eventually. Nonetheless, even if you don't agree with its belief in a moral universe, La Llorona an excellent film on its own merits, and shows some of the ways folk horror can engage with terrible histories.

Impetigore: Like La Llorona, Impetigore engages with long and murderous history, but it does so with a bit less fairy tale consolation. It is perhaps a fifteen minutes or so too long at an hour and 46 minutes, but I'm one of those weird people who thinks no horror movie should be longer than 90 minutes, so that may just be me. This is really one of the best horror movies of recent years.

The Wailing: Another excellent recent horror movie from outside the U.S., and another that I thought was too long — this time by a lot. (It's two and a half hours!) That it is still worth watching despite its length is a real testament to the film's achievement.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Perhaps my number one horror movie, certainly in my top three or four (alongside The Shining, Psycho, The Birds). I had never thought of it as folk horror, oddly enough, until I saw it among Shudder's collection. And it's something of a stretch to call it that — it lacks ritual and community beyond the family — but its inclusion does feel right somehow, perhaps because it feels like a story from a particularly nasty old song, one that would have been included in Harry Smith's (occult) Anthology of American Folk Music if it had only existed then.

Lake Mungo was, I thought, in the Shudder collection, but I don't see it there now. Perhaps they only briefly had the rights for it, or perhaps I am imagining things. In any case, it's discussed briefly and intelligently in Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched, and it's one of the best horror movies of the last 25 years. I would not have thought of it as folk horror per se until watching Woodlands Dark, where the history of the titular lake is provided, placing this film in the anti-colonial corner of the folk horror mode.