Hilma af Klint: The Spirit of Abstraction

"To paint in earth's dull colours the forms clothed in the living light of other worlds is a hard and thankless task; so much the more gratitude is due to those who have attempted it. They needed coloured fire, and had only ground earths."

—Annie Besant, "Foreword", Thought-Forms by Annie Besant & C.W. Leadbeater

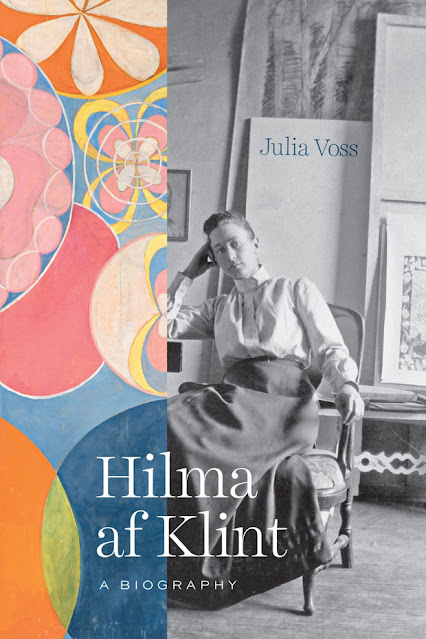

Julia Voss's recent biography of the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) is a revelatory study of a woman whose work was mostly unseen until the 1980s and not especially well known even fifteen years ago.

In 2013, Sweden's Moderna Museet put together a large exhibition which toured Europe. And then the Guggenheim Museum in New York opened a massive exhibit devoted to af Klint (Paintings for the Future) — it became their most popular show in history, with reports of visitors waiting in line for hours for the chance to see the work of an artist few had likely heard of before. In 2019, Halina Dyrschka directed an excellent documentary, Beyond the Visible: Hilma af Klint, and then in 2022 Lasse Hallström released a slick and shallow biopic, Hilma. Within the space of about ten years, then, Hilma af Klint has gone from obscurity to serious study to popularity to Hollywood-style cliché.

There is still much to see, think about, and consider. Hilma af Klint will likely always remain something of a mystery, which is also part of her allure.

During her lifetime, af Klint had some exhibitions, especially of her realistic paintings, and sought out opportunities for more exhibitions, but the abstract and symbolic nature of her major works continually posed obstacles for a mainstream audience. To what extent this bothered her is difficult to say, because so much of what she created was done for reasons beyond artistic practice. She often showed a great confidence in herself because she did not see her work as simple self-expression. She saw it as spiritual communication. She seems to have come to believe that time was necessary for the world to catch up to what she wanted to communicate, that the messages she received from the realm beyond materiality were messages for the future.

"She did not doubt her work," Voss writes, "but she doubted her contemporaries, and so she made a decision." (The translation is by Anne Posten.) In 1932 she created a code (+X) to identify all of the works that must be saved for later: "All works which are to be opened twenty years after my death bear the above sign." She was smart to choose as her heir her nephew Erik. He stored everything and did as she instructed.

In 1966, Erik af Klint and his son Johan opened the boxes for the first time since the paintings, drawings, and notebooks had been put in storage after Hilma af Klint's death.

And thus the future began.

It's an astonishing trajectory, and we are lucky to have Voss's careful, thoughtful book to guide us through the temptations of hyperbole and kitsch, the petrifying force of simplified narratives, the urge to diminish the strangeness of the past. Within the short amount of time that the world has known anything about af Klint, myths and legends have already solidified around her, and Voss quietly pries at least a few of them free.

For instance, the story of af Klint's reception by Rudolf Steiner, a man she idolized as a spiritual brother. It's a story Hallström's movie uses as a key point of conflict, heightening even the myth. The mythic story takes various forms, but the forms all revolve around the idea that Steiner was dismissive of af Klint's art; that he told her to pay more attention to her heart than her head and/or told her that it wasn't art if it was just the result of what spirit voices told her to do and/or he said her art would only be appreciated 50 years in the future; that his rejection crushed her. Like many legends, this one has elements of truth. Steiner does seem to have visited af Klint, and she certainly visited him in Dornach toward the end of his life. It seems clear from the bits of evidence that Voss has been able to uncover in various archives that Steiner preferred other artists to af Klint. Though it is reasonable to assume af Klint was disappointed that Steiner did not embrace her work more enthusiastically, there is no evidence she felt rejected by him. Voss states that "af Klint never wrote about being disappointed or that Steiner had suggested her paintings would only find an audience half a century later." The evidence that survives shows that Steiner understood the main ideas of af Klint's work when he saw it, but he didn't have much time — he was, as Voss points out, quite clearly in a hurry between appointments while visiting Stockholm, probably in January 1910 (there are no dates on the surviving notes of the visit). "The situation was probably less than ideal," Voss writes, since "af Klint had given up her studio at Hamngatan 9, so Steiner was confronted with an overwhelming multitude of works, presumably in a cramped space."

The uncertainty around this visit between af Klint and Steiner exemplifies a lot about her life and art. While her archive is huge — over 1,200 works of art and 26,000 pages of writings — there is very little personal information in it. For most of the events of her life, any statement we make about her feelings is speculative. There is documentary evidence for a lot of what happened in her life, but very little about her emotions or opinions. Nonetheless, from here in the future, we yearn to place a sense of her self into the story of her art — exactly what she sought to avoid.

Voss does a nice job of not marginalizing, trivializing, or explaining away af Klint's spiritual beliefs; she also allows us to see af Klint as someone with serious scientific interests for whom spiritual experiences were often a type of research. From her late teens to the end of her life, af Klint felt herself in conversation with both the spirits of dead people and with ethereal beings who, she believed, offered her a vision of a world beyond materialism, a world where dualism was resolved, where genders were fluid and united, where energies like love provide sustaining, generative power. Her beliefs were real and meaningful to her, providing the primary justification for her art, and so must be treated with the seriousness with which the beliefs of artists who held more familiar or traditional philosophies and religions are treated. Voss does so. Much work still remains to be done, though, particularly by scholars with deep knowledge of Theosophy, the occult, and especially Anthroposophy. The implications and meaning of af Klint's interest first in Rosicrucianism, then Theosophy, and then Anthroposophy are many, and those implications and meanings are unlikely to be well presented by anyone without knowledge of the nuances of the beliefs.

I would be especially interested to see an analysis by someone with deep experience of Steiner's writings and Anthroposophy who could delineate to what extent af Klint's approach fits within or deviates from mainstream Anthroposophy. She does not seem to have considered herself to be an iconoclast — in 1943, rejecting an offer to have her work preserved by an organization associated with another faith, she responded that her outlook was that of an Anthroposophist, her work the work of an Anthroposophist. Voss quotes a letter from af Klint to Tyra Kleen in September that year: "Putting the work one day in the hands of people who do not have an Anthroposophical outlook might be problematic."

Just how problematic is clear from Hallström's movie. In Hilma, af Klint's spiritual experiences are presented first as trauma after her sister's Hermina's death at age 10 in 1880. (The cause is unknown, but Voss says it was most likely pneumonia.) Though certainly the death was a great loss for Hilma, and she kept her sister's memory alive for the rest of her life, Erik af Klint said his aunt told him her spiritual experiences went back to her childhood. At least from Voss's narrative of Hilma's life, she doesn't seem to have attached any particular change in beliefs or sense of the universe to Hermina's death. Indeed, by 1879, a year before the death, af Klint had met and begun working with the artist and spiritualist Bertha Valerius, and the oldest notebook in the af Klint archive documents (among other things) séances af Klint attended in 1879 where Valerius channeled voices of various beings: "the spirits that Vlaerius called during the séances," Voss writes, "came in friendship. They brought good news from the beyond: news of love, joy, and happiness."

Hallström's presentation of this sort of material ranges from embarrassing to embarrassed. Hermina is depicted in gauzy light, a visual cliché representing little more than stock sentimentality. The scenes of af Klint and her friends involved in spiritual activities are perfunctory, missing both the philosophical seriousness with which the actual people engaged in such work and the significant portion of their lives they devoted to it. In the film, the older Hilma seems to be little more than a disappointed old lady on the verge of dementia — a representation that is a real betrayal of the actual Hilma af Klint. The spiritual is simply not what interests Hallström, and so he misses the story of Hilma af Klint and her art.

(The only contemporary filmmaker I can think of who might be able to capture some of the spirit of Hilma af Klint cinematically is Terrence Malick. The Tree of Life has much more in common with Hilma af Klint than Hilma does.)

The story of her art is also a story of gender, and particularly of women. Af Klint's beliefs led her to embrace what we would now think of as gender fluidity, or the transcendence of gender. It was based on ideas going back to Plato's Symposium, a common reference point among progressive thinkers about sex and gender at the time (including Theosophists), but af Klint went a bit further than others. Like her contemporaries, she had a hard time thinking outside the dualistic roles of man/woman, writing of "womanman" and "manwoman", saying, "Many female costumes conceal a man. Many male costumes conceal the woman." This is not far from Blavatsky's own concept of androgynous deities and the androgynous origins of humans, ideas which recur regularly throughout The Secret Doctrine. But even as af Klint worked from concepts based in two human genders, she sought to escape the limits and strictures of gender altogether. Voss writes: "For her, the blurring of the boundaries between the sexes was the freest state of the soul. Not only that: she argued that the spirit strives toward such a state, following the law of completion, the longing for union that is characteristic of all living beings."

In the material world, af Klint's own sense of union seems to have been entirely with women. Something that Voss's biography makes clear and even Hallström's movie depicts fairly well is the extent to which af Klint created for herself a communal world of women. This goes beyond the fact that her two great loves were women (Anna Cassel and Thomasine Anderson). From her earliest spiritualist explorations until at least middle age, her social, spiritual, and artistic life centered around groups of women. She designed and built a studio in Munsö for the purpose not only of housing her paintings but also of offering a refuge and residency for research into plants, animals, and minerals. "Henceforth," she wrote, "our work is not separated from each other."

Though she seems to have shown no yearning for marriage, it would not have been in her best interest even if she were so inclined: a Swedish law of 1870 granted women rights as legal adults and the right to a profession — but those rights disappeared with marriage. Sexism was baked into many supposedly scientific concepts, and the art world was often explicitly and prohibitively sexist. Experimenting in communities of women, af Klint discovered that all the various qualities of personality necessary for life and union were present, and the worst features of sexist society were held at bay. Men were often an obstacle and generally a hindrance during her life. She was better off without them. By her own choice, however, it would be a sensitive, thoughtful man (her nephew) who would deliver her work into the future.

She spent much of her life building community with women, but this is not to say that those communal experiences were always delightful for her or the people around her. Hilma af Klint was a confident woman who came to dominate all of the groups she chose to associate with, sometimes causing tensions. She had not just a strong will but a strong vision. At times, it was probably thrilling for her compatriots to surrender themselves to her extraordinary intuition and talents, but it must have been exasperating sometimes for the other women to be faced with Hilma declaring that they must follow her lead because that's what the spirits command.

Since her time with Bertha Valerius, af Klint had made notes, sketches, and drawings influenced by or under the command of spiritual forces, work that often took a geometric or abstract form. 1906 brought something new: the Primordial Chaos series, the first of the Paintings for the Temple. These were works that af Klint thought of as commissions from the mystic beings she and her group of seekers called the High Masters. The paintings from 1906-1908 were completed mediumistically, like large-scale versions of the automatic drawings she and her fellow believers had been practicing with for a while. The results were sometimes symbolic, often entirely abstract. Then in 1912, af Klint began the second group of Paintings from the Temple, beginning with the US Series, and now the spirits commanded her to take more control. In a notebook, she recorded them as saying, "It is hereby intended that you (H) be trained as a willing servant to work for one year on our idea starting roughly from today, not in a mediumistic manner but independently." (Quoted in the foreword to Catalogue Raisonné Vol. 2: The Paintings for the Temple.)

The question of abstract art has been a frequent and not especially illuminating one in discussions of Hilma af Klint's work. Because so much of popular and scholarly art history has been dominated by a male perspective, there is an understandable desire to push against the idea that abstract art began with men (Kandinsky, Mondrian, etc.). In an important way, it's absolutely true that abstraction wasn't "invented" by a male artist. Depending on how you want to define abstraction, it's easy enough to point to someone like Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884) and dispense with the Men of Abstract Painting narrative. However, there are two complicating factors: first, the lack of influence of women artists in comparison to male artists because of the stubbornly patriarchal assumptions of the art world until very recently; second, the challenge of defining what abstraction means.

Abstract art by women has only recently begun to be influential, either because it was dismissed by artists, critics, and collectors who clung to sexist assumptions, or because, in af Klint's case at least, it was unknown and literally inaccessible. (Often, in fact, the two go together: an artist is marginalized because of sexist assumptions, rendering their work invisible.) Once we move beyond the problem of assumptions that make some art valued and similar art not, the remaining questions of influence, of who got there first, of who did it best are all little more than parlor games, because with a broad concept like abstract art, a concept with numerous definitions and delineations, there can be no satisfying origin story.

More interesting to explore is the value of abstraction to artists — of what we might call the affordances of abstraction. What does abstraction allow that representation does not?

In the case of Houghton, af Klint, Kandinsky, and plenty of other artists, that question brings us back to spirituality. This was clear even from the beginning: in the 1870s, after a small exhibition of Georgiana Houghton's spiritualist paintings, Houghton's approach was interpreted as in line with Asian (particularly Buddhist) art by Sir Henry Yule and by Madame Blavatsky herself in a footnote in Isis Unveiled, quoting Yule on Houghton's exhibit. For Julia Voss, the history of abstraction in art is a history of the spiritual in art, beginning "in 1857, when the English writer Camilla Dufour Crosland recorded her experiences with spiritual apparitions and furnished her book [Light in the Valley: My Experiences of Spiritualism] with nonrepresentational illustrations and those by the artist Anna Mary Howitt."

What for lack of a better word we call abstraction was a necessary tool to provide a glimpse of the immaterial world. Voss writes: "The communications, revelations, or disclosures came from another dimension where the spirit had freed itself from matter, from objects and things. It was therefore no longer an issue of depicting something. If content determines form, abstraction is the natural mode of the spirit." One quibble with that description comes to mind: such art is "depicting something" — but the something is beyond the reach of straightforward representation. Functionally, such art is the equivalent of illustrations in a physics textbook's chapter on quantum mechanics.

Af Klint tends to be referred to as a mystic, and that's certainly not wrong, but this label diminishes the importance of science to her art. The overlaps between science and mysticism have been lost to an age that likes to think of itself as disenchanted, but as Voss points out repeatedly, there was no contradiction in af Klint's mind between her spiritual and scientific investigations. (To his credit, Hallström depicts this from the beginning of his film.) This was an artist who painted whole series titled Evolution and The Atom. Her early work included numerous realistic botanical drawings. She and Anna Cassel worked together at the turn of the century at the Veterinary Institute in Stockholm to create detailed anatomical drawings of animals, including the reproductive organs, which allowed them a type of biological knowledge generally unavailable to women at the time: "They studied," Voss writes, "the penises of stallions and learned how testicles were removed during castration. They drew the vaginas of mares and studied the reproductive process from fertilization to birth. They experienced the blood, mucus, and excretions of the animals. They learned about the methods and tools of medical research: heightened observation, illustrations, measurements, cross sections, models, highly specialized instruments." This experience would have noticeable effects on af Klint's later paintings.

For af Klint and many spiritualists, science was not separate from the occult. Voss quotes the Theosophist Charles Leadbeater in 1902 on atomic discoveries: "Occult science has always taught that these so-called elements are not in the truest sense of the word elements at all; that what we call an atom of oxygen or hydrogen can under certain circumstances be broken up." With science providing so many discoveries of invisible phenomena and forces such as light waves and x-rays, it would be difficult at that time not to see science as a kind of confirmation of occult conceptions of the universe. A work Leadbeater wrote in collaboration with Annie Besant, Occult Chemistry, is one that offers some visual clues to af Klint's art — graphs and illustrations in it have some commonalities with af Klint's paintings at the time. (Af Klint may not have read the book itself, but she was almost certainly familiar with preliminary versions and excerpts in periodicals. Other books by Besant and Leadbeater were in her library. Thought-Forms is another Besant/Leadbeater text of likely significance for af Klint's art.)

As work on the Munsö studio finished in 1917, af Klint laid out her vision for its purpose: "First I will attempt to understand the flowers of the earth; I will take the plants that grow on land as my starting point. Then, with the same care, I will study what lives in the waters of the earth. Then the blue ether with its myriad creatures will be the subject of my study, and finally I will penetrate the forest, exploring the silent mosses, the trees, and the many animals that inhabit the cool, dark undergrowth."

For all its mysteries and developments, the art of Hilma af Klint shows remarkable unity of vision. Voss sums up this vision well at the beginning of her book: "Her works, she believed, could help us leave behind everything that makes the world small and rigid: entrenched thought patterns and systems of order, categories of sex and class, materialism and capitalism, the binary view of an Orient and an Occident, and the distinction between art and life." The prevalence of series in her work shows this: no one moment or painting is enough to convey meaning. The flow of time, of experience, of perception, of the spiritual and material realms — this flow can only be represented through the multiplicity a series offers. Af Klint insisted that her abstract paintings be kept together because if we are to have any hope of understanding what she wanted us to understand, we must look beyond individual images.

As her archive continues to get attention from scholars and historians, it will be interesting to see what new insights can be gleaned about the progression of af Klint's style. The Guggenheim show that brought her such extraordinary attention was not a complete career retrospective but primarily a presentation of her major paintings from 1906 to 1920, with some work from earlier and later added for context. That selection makes sense and allowed the world to see the major series as she hoped they would.

(And — in one of the great and delightful weirdnesses of her life and post-life — the art was displayed in a white spiral building, which is what af Klint herself described as the temple at which her paintings ought to be shown. She tried to get such a temple built, but it proved impossible. Interestingly, the painter Hilla von Rebay, who was Solomon R. Guggenheim's art advisor and the main instigator for the Guggenheim Museum, was well read in Theosophy and Anthroposophy, and even attended lectures given by Rudolf Steiner when she was a teenager. She described the museum she envisioned as "a temple of nonrepresentation and reverence". Hilma af Klint would have approved.)

However, the earlier and later paintings also have much to recommend them. The watercolors in particular are richly evocative, and important spiritually — the wet-on-wet painting technique she worked with from 1922 to her death was one advocated by Rudolf Steiner and the members of the Anthroposophical Society. Watercolor became her main technique for the last decades of her life, but she would sometimes return to oil. Voss reports that her final oil paintings were four she made in 1941, "all of women dressed as nuns."

While the Paintings for the Temple are astonishing in their size, color, and energy, and the later watercolors evocatively ethereal, af Klint's work from around 1917 to 1920 shows another style, though with similar purposes as before and after. In various untitled series, af Klint's art became highly geometric. This was at a time when she decided to commit herself to Anthroposophy rather than Theosophy, apparently preferring Steiner's more Christian vision to that of the eclectic and Eastern-influenced occultists. At the same time, she was thinking about the variety of religious experiences in the world, seeking their overlaps as well as unique offerings, a search which led to the extraordinary Series II of 1920: eight images made with oil and graphite on canvas and with individual titles such as "The Current Standpoint of the Mahatmas", "The Jewish Standpoint at the Birth of Jesus", and "Buddha's Standpoint in Earthly Life". Most of these paintings are circles filled with varying amounts of black and white until the last two pictures, "The Teachings of Buddhism" and "The Christian Religion", which introduce purples and reds as well. There is a fierce and graphic minimalism to these paintings, a powerful stripping away of elements so that we must meditate on the few elements present, a focused mystery.

In the summer of 1928, af Klint traveled to London for the World Conference on Spiritual Science, a large Anthroposophical event where some of her paintings (likely ones from the Paintings for the Temple series) were displayed and where af Klint gave an address about her work. This was arranged by a Dutch friend af Klint had made when visiting the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland, and whom she later visited in Amsterdam, a dancer and actress named Peggy Kloppers-Moltzer. (It was during that 1927 visit to Amsterdam that af Klint first mentioned Kandinsky's name in her notebooks: "Kandinsky, pure colors, planes," she wrote.) Kloppers-Moltzer was passionate about af Klint's paintings, but failed to find any support for an exhibition among Dutch Anthroposophists. After that failure, she and af Klint worked hard to convince the international conference to provide space for the paintings, and this time they succeeded. The paintings were shown at the Friends House on Euston Road.

Nothing is known of what af Klint said in her 1928 address in London. There are notes, however, for a lecture she gave in April 1937 in Stockholm to the Swedish Anthroposophical Society, where she talked about her work and its mysteriousness even to her. "She could not explain who the beings were who contacted her," Voss writes. "Not even Steiner, she told the rapt audience, had been able to help her — his advice had been for her to find the answer herself." She noted a difference between herself and Steiner, who had advocated for actively seeking knowledge beyond the earthly realm, while af Klint said, "My life comprises the understanding of how to receive help, and the struggle to make my own what I have already received. ... Every time I succeeded in executing one of my sketches, my understanding of man, animal, plant, mineral, yes, of creation in general, became clearer. I felt that I was freed, and raised above my more limited consciousness." Art was for her investigation, exploration, communication — she believed "that the way of a painter or musician makes it easier for us to come into contact with other souls." (All quotations from Voss p. 285.)

From these ideas and experiences we can get a sense of why af Klint did not seek out traditional exhibitions for her work even in the years when modernism had exerted enough of an influence on the public to make a positive reception more possible. She used her talent and skills to make art she could sell when she most needed to — veterinary illustrations, portraits, traditional landscapes. (The full extent of these works isn't entirely known because she sold them and they are now scattered through private collections.) She seems to have believed that it would have been monstrous to turn spiritual explorations and expressions into commodities. She tried to give the paintings to a good home, but even the Goetheanum rejected most of her donations. (While the paintings' uniqueness certainly worked against them, there were likely also practical considerations for the potential receivers of the donations — the major paintings are huge and there are a lot of them. Storage would be a challenge, and exhibition even more so.) Luckily, af Klint sensed that her nephew Erik would be a good caretaker of her life's work, and she was correct.

Here we are now, the people of the future, able to see and, to some extent at least, appreciate this extraordinary artist. I wonder if Hilma af Klint would consider us any better than her contemporaries, however. After all, we are appreciating her work as art. We talk about the paintings' form and color, but I doubt many of the visitors to the Guggenheim or other exhibitions have seriously engaged with the work as communications from ethereal beings in a world beyond our own. (I certainly haven't! I don't for a minute believe in the persistence of individual consciousness after death, nor do I believe in angelic beings.) Perhaps, though, af Klint would not mind that most of us don't share her particular view of the world. Perhaps she would say that her art is not about conveying dogma, but about encouraging us to imagine beyond the material limits of the world, to consider our deep connections to each other, to animals, to the planet, to the universe. Regardless of the various religious and spiritual beliefs she held, that sense of connection was consistent throughout her life. I don't want to trivialize it in her art, don't want to turn her life's work into platitudes about peace, love, and harmony. There was a ferocity to Hilma af Klint, a stubbornness and confidence that comes through despite the deliberate absence of personal reflection in her archive. I have no doubt that she would be disappointed in this future of ceaseless violence, this world we have wrecked with our greed and shortsightedness, this era of material obscenity and spiritual impoverishment.

Which is why we so desperately need her work now. Most of us may not share her metaphysics, but we should have less trouble sharing her values. Her art offers us a way to reflect on those values, and to find their place in our own sense of life.

I can't help but think of another woman of determination and complex ideas, Virginia Woolf, who lived right around the corner from Friends House when af Klint showed her paintings and gave her lecture in 1928. Just the day before, Woolf had left London for Monk's House in East Sussex for the summer, having just finished correcting the proofs of Orlando, her gender-bending love letter to Vita Sackville-West. At Monk's House, Woolf and E.M. Forster would talk about Radclyffe Hall's lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness, which had recently been banned for obscenity.

I am consumed by a fantastical wish that Woolf and some of her friends might have stayed in London a few days longer, have made their way to the conference, and peeked in at af Klint's paintings. (Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant might especially have appreciated af Klint's sense of color and form.) None of the Bloomsbury folks shared af Klint's Anthroposophical beliefs, but they might have found some common ground in their shared idea of art as a way of coming into contact with other souls (if we don't define souls too religiously). That idea of contact seems to me a common theme of Woolf's fiction, which yearns so often for connection and unity, for bringing together the macro and micro, the world and the people.

The Waves is, in its own way, a mystical novel. I wonder what af Klint would have made of it. (She didn't read English and as far as I know it wasn't translated into Swedish until 1953.) The sea was important to af Klint, whose family included many distinguished sailors, and so the title might have intrigued her. It is a novel of voices and visions, of death and life (of life in death, of death in life). It reads, at times, like a séance.

As with so much having to do with af Klint, we can only speculate.

Rather than anything from The Waves, to conclude our rambles here I must bring in Lily Briscoe, the painter in To the Lighthouse — indeed, I can think of no better conclusion than the novel's own final paragraph:

Quickly, as if she were recalled by something over there, she turned to her canvas. There it was—her picture. Yes, with all its greens and blues, its lines running up and across, its attempt at something. It would be hung in the attics, she thought; it would be destroyed. But what did that matter? she asked herself, taking up her brush again. She looked at the steps; they were empty; she looked at her canvas; it was blurred. With a sudden intensity, as if she saw it clear for a second, she drew a line there, in the centre. It was done; it was finished. Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.

-----

Images: all by Hilma af Klint except the photograph of the Guggenheim exhibit and the black and white diagram from Occult Chemistry by Besant & Leadbeater