Sinéad

When music gets you, it goes deep. Schopenhauer believed it's the only art that goes past the illusions of life and expresses — even exists at — the base level of reality itself. Anyone with a sensitivity to music knows that there is nothing else that so quickly mingles with emotions and memory. Which perhaps is why we experience such a wrenching ache at the death of any artist behind the music that remains most entangled with our emotions and memories.

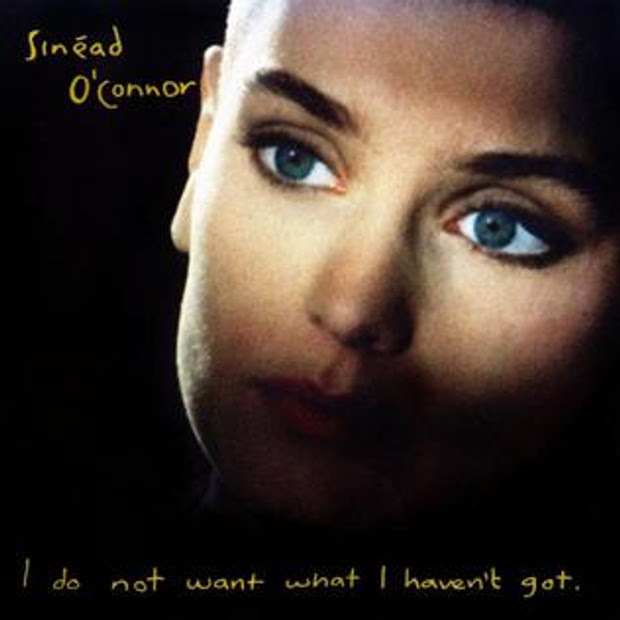

I was surprised by the force of feeling that struck me when I heard the news of Sinéad O'Connor's death. I hadn't been playing her music all that often these days. I'd revisited it pretty significantly after watching the (excellent) documentary Nothing Compares a year or so ago, but that was only for about a week. Not like when I was in high school and I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got lived in my CD player.

Today, the hearse carrying the body of Shuhada' Sadaqat made its way through the seaside town of Bray, Ireland to a private burial service. I don't write about her with her chosen name because my experience of her is not of that person but of the public figure who was Sinéad O'Connor. But I rarely have ever thought of her by last name as I would most other public figures and many other cherished musicians and artists. She was always just Sinéad.

That inability to think of her as anything but Sinéad signals the sense of intimacy her work inspired in so many people. Often, the use of only a first name for someone can feel disrespectful. I didn't know this person, never interacted with them, they never knew of my existence. There's a particular danger in a patriarchal society to referring to women only by their first name. It can be trivializing, infantilizing. That danger remains, but still — I remember lying on the floor of my bedroom, headphones on, listening to the a cappella title song of I Do Not Want... and feeling welcomed into something like a meditative experience, feeling that somehow I had been given a mantra, a path, a way forward. Millions of other people felt the same, I am sure. And how could we think of the voice that bestowed this gift in anything other than a familiar way? How could we think of this as coming from "O'Connor" — from anyone other than Sinéad? And so she always remained for me.

Like so many people, I first noticed Sinéad O'Connor via the video for "Nothing Compares 2 U". It was released in early 1990, so I would have been 14. I could watch MTV occasionally in the afternoons while my parents were at work. I remember first seeing her face — I thought I was looking at the most beautiful boy I had ever seen. Quickly enough, I realized this was a woman, and I was beguiled. The video was terrifying and enchanting to a kid whose feelings about gender and life and everything were already all over the place. Even now, it's a powerful piece of cinema. Her face is striking, but it's the melding of physical and musical performance that makes it so powerful.

One of the hallmarks of Sinéad's work for me is its ability to move from crystalline beauty to razor-edged fury in the space of a single note. In the video we see her astonishingly expressive face do the same. But without mugging — that's the important point. This is no Jim Carrey performance! In a tiny change of gaze, her entire mien shifts. It's breathtaking, transfixing.

And of course there was the hair. If you weren't alive in 1990, you may find it hard to believe how perplexing and shocking that shaved head was to so many people, especially heterosexual men. I loved her hair the moment I saw it, but reading Amanda Marcotte's tribute to Sinéad I immediately remembered switching the channel away from the video if my father was in the room. Marcotte writes:

I was 12 years old when "Nothing Compares 2 U" came out, and I had to pray the video would only show up on MTV when no father, stepfather or uncle was in the room. I just wanted to wallow in Sinéad's perfect, gorgeous song without hearing snide remarks about her (lack of) hair.

The scorn that haircut caused was astonishing, and in retrospect I hardly believe my memories of it, but then I remember that the repulsion and visceral hatred my father's face displayed when he saw that video was the same I saw from him a little later when Hillary Clinton was on tv. Marcotte explains it in a way that sort of gets at that — "It was only years later that I realized what they were so mad about: They resented the implication that a woman has a right to exist for a reason other than pleasing a man." — but I think it was deeper, even more atavistic. It was, yes, about withholding a certain type of (hetero) male pleasure, but it was also something about power, vulnerability, beauty, and how they all mingle within a single person and a single song.

I did not buy many CDs in 1990 (they were hugely expensive!), but I got I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got on CD. Hearing the other songs was a revelation. The only comparable experience I'd had with music had been when I got Tracy Chapman's first album (on tape) a year and a half or so earlier. I'd loved "Fast Car" — I even remember when I first heard it: sitting in a car with friends going up to summer camp, the song came on the radio, and I said something about liking "his voice" and one of my friends looked at me like I was the stupidest person who ever lived and said, "Tracy Chapman's a girl." (You might be noticing something about the singers I fell hard for when I was a kid...) Chapman's album was a mindblower for obvious reasons — beautiful music, but also ... well, you can imagine how little exposure I had as a young teenager in rural New Hampshire to the ideas in songs like "Talkin' 'bout a Revolution" and "Behind the Wall" and "Mountains o' Things" and — the whole album, really. It began an education.

I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got continued that education. As a male-identified only child in a fairly remote place, I had little access to female experience or emotions, and Sinéad provided a view of existence otherwise inaccessible to me.

I didn't know what "Three Babies" was about, but the simple, ethereal, yet visceral way she sang it conveyed something far beyond the lyrics. (The face of you ... the smell of you ... will always be with me.) Then came "Emperor's New Clothes", a song that quickly became one of my favorites on the album, not only because of its great beat but because of its defiant stance. That stance welcomed me in — I was a nerdy kid in a world without much room for such beings, I was desperately trying to hold onto a vision of a way to escape, and lines like "I won't go anywhere nice for a while, all I want to do is just sit here and write it all down and rest for a while" spoke to me in the way that things perhaps only Speak To You when you're a teenager. But then to identify with the song, which I did, I also had to identify with the other lyrics: "I would return to nothing without you if I'm your girlfriend or not" and that astonishing chorus: "If I treated you mean, I really didn't mean to. But you know how it is. And how a pregnancy can change you..." I loved how Sinéad sang that last line, loved singing along and trying to match her pronunciation: How a pragggnancy can change you, which meant having to imagine my way, at least a little bit, into the emotional space of a pregnant woman. I read lots of science fiction back then, but little of it ever expanded my brain to the same extent as those simple lines of music.

And then "Black Boys on Mopeds". I don't really know how to write about that song. It was a song I was deeply attracted to for its music and deeply frightened of for what it made me think about. I remember what it felt like, I have an intellectual understanding of my experience, but I'm so far away from my younger self now that it's hard to recapture the seismic force of that song on my understanding of the world. All I can really say here is the moment I heard of Sinéad's death, that song came into my head, and not just that song but a specific line: "If they hated me, they will hate you." That was the line that bonded us. That was when she first became Sinéad for me.

That song is also why I was always heartily on her side after the Saturday Night Live incident. I stayed up to watch it. Not really knowing any of the context, not being Catholic, I didn't really understand it in the moment, but I noticed all the condemnation of her, the jokes and the supposed outrage (were people really outraged or were they just indulging in the same feelings that caused them to scorn her when they saw her shaved head?). I don't think I am aggrandizing my past self when I remember that I only ever felt solidarity with her. "Black Boys on Mopeds" had prepared me. These are dangerous days. To say what you feel is to dig your own grave.

The fall of 1990, I entered high school. I got cast in a play, Crimes of the Heart, where most of the other actors were senior women. Somehow or other, they found out I liked Sinéad's music. (None of my male friends did. Quite the opposite. Even to admit that you liked it felt like admitting to being a fag. I certainly wasn't going to do that!) One of them loaned me her tape of Lion and the Cobra and said, "Listen to 'Troy'." "That's the great song," another said. "That's the song." I listened to the whole album, but I really didn't get it. The music felt more alien to me than the music on her second album. I especially didn't get "Troy". I had no frame of reference for any of it, musically or literarily or emotionally. But I remembered that this was something of a sacred song for my friends, friends who seemed immensely older and wiser than I was, more experienced with the world, and I kept coming back to that song (I'd copied their tape onto a blank tape of my own). The force of that song, its beautiful fury, scalded me when I first heard it, but eventually its beauties found their way into my ears, and its edges became my own.

I got Sinéad's other albums as they came out, up through Faith and Courage in 2000, then, like many people, lost track of her. I heard about some of her mental health challenges, some of her erratic behavior, but I always thought ... well, of course, she's Sinéad O'Connor. She's tremendously sensitive and the world has put her through the wringer again and again, why would we expect her to be other than she is? In some ways, I took her for granted. She had been so strong for so long, I just assumed she would always be able to bounce back. I didn't realize that I assumed she would always be there.

After watching Nothing Compares, I explored her later albums, and was pleased to discover that despite the ups and downs of her career and life, her music remained powerful, innovative, beautiful. There's nothing like her first two albums, those stunning eruptions of beauty and fire, but so what? Nobody could sustain the power of those albums and stay alive. Her voice remained unique.

This morning, I read a Reuters article about the funeral procession through Bray. A comment from one of the onlookers got me: "She represented our transition from a very dark past into a hopeful future and I'm just here to say thanks for being with me along that journey, and for maybe putting words and expression on what I felt but didn't quite know how to say."

The outpouring of love for Sinéad in these days after her death has sometimes felt like something that came too late. Where were the famous people full of compassion when she was alive? There were some, certainly, but not enough, especially not when it really mattered, when it was really hard. Compassion is an affectation when you only save it for the people it's easy to feel compassion for.

Maybe we can learn from that, too. Maybe that's something she's been teaching us, something she will continue to teach us as we play her music, as we listen to recordings of her astonishing voice.

This beauty didn't come from someone who was always easy to understand, always easy to get along with, always easy to hold close to the heart. But she was alive, and she herself had tremendous generosity and compassion when she was able, because she knew how it felt to be a raw nervous system in a punishing world. She knew. It's why we loved her, why we listen to her, why we mourn her so deeply.

After Sinéad, I went on to find solace in the music and voices of Billie Holiday, Tori Amos, PJ Harvey, Patti Smith, and Ani DiFranco. Male musicians would be important in their own way, but when I think of the deepest musical connections I felt in my high school and college years, it's those women who come to mind, and they're the musicians I think of now as I think of her and all she gave to this world.

Go forth now, Sinéad, with our love. Be at peace. There is no other Troy for you to burn.