Will Lasky at The House Next Door

Will Lasky at The House Next Door suggests that

The Fall is destined to be a cult classic, and that seems right to me. It's a movie that causes viewers to split quite strongly, some feeling the film is visionary and powerful, others finding it pretentious and boring. Inevitably, as we try to tell people what we thought of the movie and what the experience of watching it is like, we compare it to other films --

The Princess Bride comes up a lot, but I think that's a bit misleading, and likely to cause dissatisfaction in a viewer who watches

The Fall expecting the other film's

whimsy. A closer approximation would be Terry Gilliam's

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, a movie that is as full of stories-within-stories as

Princess Bride and

The Fall, and also shares

The Fall's darker view of human motivations, attention to imagery, and sometimes messy (some might even say

flabby) narrative structure. The other particularly valid comparison, I think, is to the films of

Julie Taymor -- there's an animation sequence in

The Fall that is reminiscent of

the one The Brothers Quay did for

Frida, and director

Tarsem says in the commentary for

The Fall that he'd originally planned to get The Brothers Quay to do his, then he saw

Frida and realized they'd just done it. So he went to different twin animators,

the Lauensteins. There are certainly other similarities to Taymor's work as well, especially the careful visual construction of every scene and the strongly divided reactions among viewers.

What can't be denied is that again and again

The Fall is visually gorgeous. This has, for some

critics, been one of its weaknesses -- bright, colorful beauty is something we have learned to distrust in movies. (Notice how much praise there is for the murky mess of

The Dark Knight. [Sorry, I've really come to hate that movie.]) There is a suspicion, even as we are impressed by the framing and the vivid hues, that many of the shots in

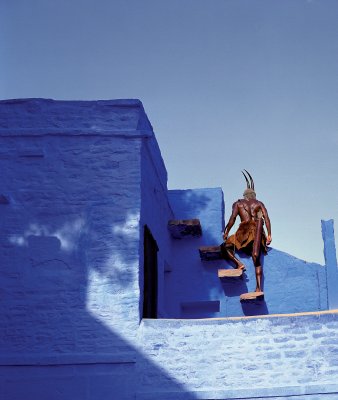

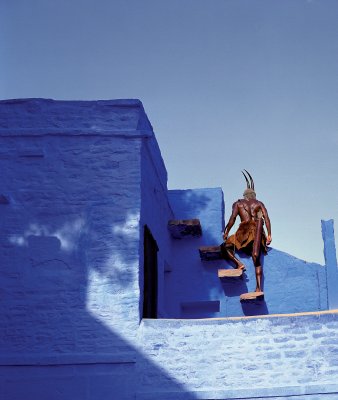

The Fall are not art, but kitsch: 3-D Dalí.

For me, there were a few mitigating elements that moved the imagery decidedly into the realm of art and out of the trash-heap of kitsch. First, like Dalí's best paintings, the imagery is striking, forcing an involuntary, whispered "Wow" when I first saw a few of the shots. We are not in the realm of

Thomas Kinkade.

Second, and perhaps more important, the imagery makes sense within the conceit of the movie. The entire film is filtered through the perceptions of the child Alexandria, stuck in a hospital after breaking her arm in a fall while picking oranges with her family, migrant workers in the early twentieth century. She wanders through the hospital and meets Roy, a silent-movie stuntman who has been paralyzed after falling from a train trestle in a dangerous stunt, one he performed, it seems, to try to win (back?) the love of the movie's leading lady, who has become the girlfriend of the leading man. Roy's body and heart are broken. He begins telling Alexandria a story of a group of heroes who seek to destroy an evil Governor Odious.

Roy tells the story using the most exotic characters he can think of, including Charles Darwin and an Indian. We quickly discover that we are in Alexandria's imagination, though, when, despite Roy mentioning the Indian's "squaws" and "wigwam", the Indian on the screen actually lives in India. Alexandria's frame of reference is different from Roy's. Little details throughout the movie remind us of this.

The imagery also makes sense in contrast to the more objective reality of the hospital, which, though beautifully filmed, has a much more restricted color palette and tighter, less epic cinematography. Alexandria's imagination is full of vivid beauty.

The performances are also notable, particularly the leads -- Lee Pace as Roy manages to find considerable range in the role, and is particularly fine in small, intimate scenes with Alexandria. And Catinca Untaru as Alexandria is phenomenal, giving easily one of the best performances by such a young child that I've seen. Her character, in more than one way,

is the movie, and Untaru entirely lives up to the challenge.

Along with the imagery and Catinca Untaru's performance, what most impressed me about

The Fall was the courage of its ending. It is sweet and touching without being sentimental, because Tarsem allows Roy's story to grow very dark as Roy himself loses hope in life. Alexandria is too naive and too determinedly idealistic to allow the darkness to fully enter her imagination, though -- she fights Roy to bring the story back to a place of beauty, and the effect is that the story does not change her, as much as it amuses her, but it does change Roy. Or perhaps not. Tarsem has been criticized for being too much of a pop artist, too much still the guy who made TV commercials and music videos, but the criticism is superficial and ignores the tremendous ambuity of the ending and the unreliability of a very young narrator. The final section, with Alexandria narrating action scenes from old silent movies, brings the grand imaginings of the earlier sections of the film toward a simpler kind of beauty, though one that is equally faithful to the idea that imagination is not an escape from reality, but a tool with which to understand and even shape it. The meaning of

The Fall is, in the end, left up to us to decide, interpret, and imagine. That, more than anything else, makes it a work of art.