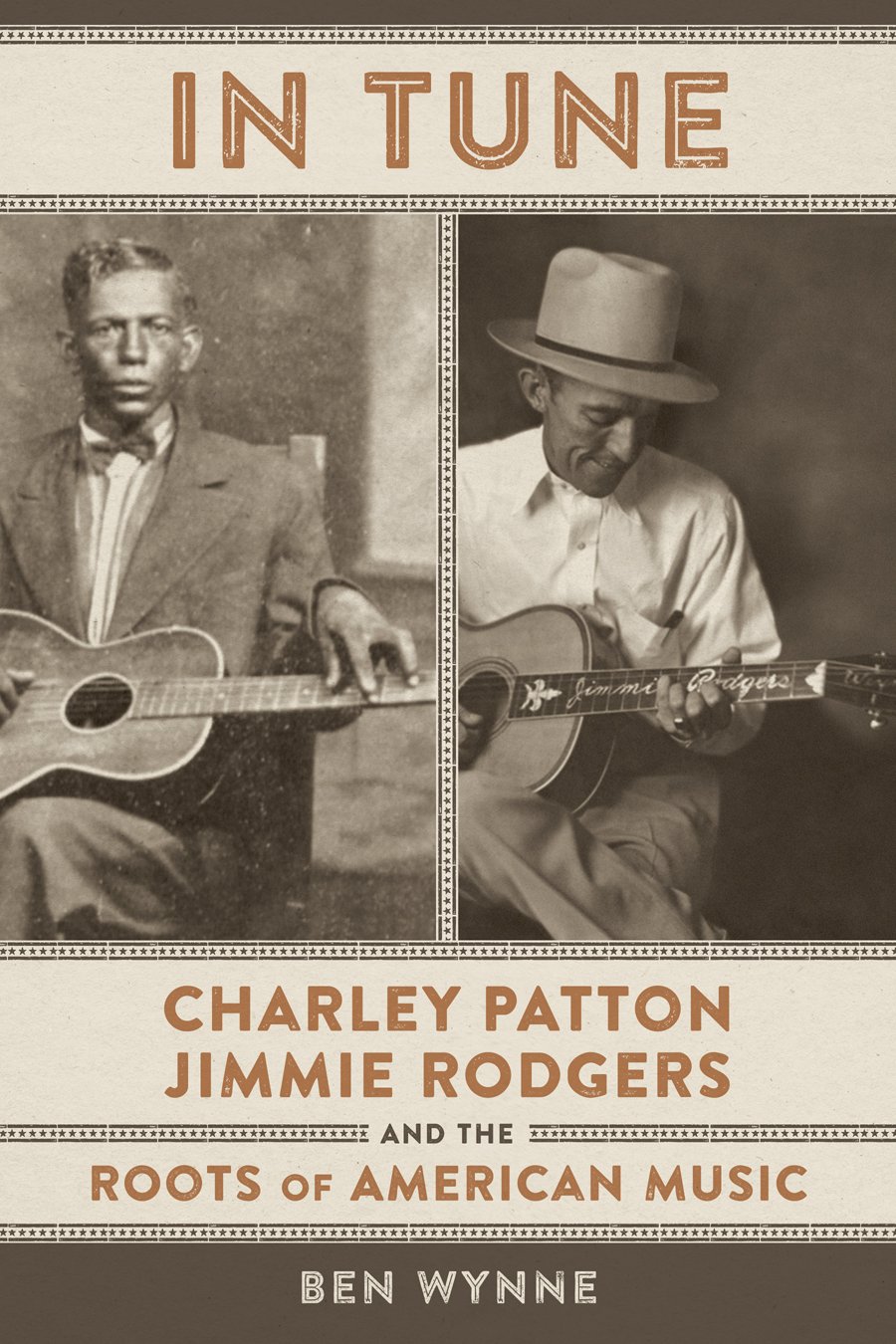

In Tune: Charley Patton, Jimmie Rodgers, and the Roots of American Music by Ben Wynne

The review originally appeared in the Summer 2015 issue of Rain Taxi.

In Tune: Charley Patton, Jimmie Rodgers, and the Roots of American Music

by Ben Wynne

Louisiana State University Press

“Today,”

Ben Wynne writes, “the names Charley Patton and Jimmie Rodgers are rarely

uttered outside the confines of documentary films or scholarly publications

dealing with American roots music. Most people do not routinely listen to

Patton or Rodgers records, and their songs are no longer heard on the radio.”

[14] And yet the music of Patton and Rodgers echoes through most popular music

from the middle of the 20th century to now, because Patton was one

of the foundational figures of the Mississippi Delta style of blues and Rodgers

was one of the foundational figures of what today is known as country music.

From Patton and Rodgers we can trace a direct line to Robert Johnson, Bill

Monroe, Hank Williams, Howlin’ Wolf, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee

Lewis, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton,

and countless others.

Patton and

Rodgers were both born in the last decade of the 19th century in

Mississippi, and they died within a year of each other: Rodgers in May 1933 and

Patton in April 1934. They grew up poor, and learned early that their musical

talents were a way to escape the everyday life of a farmer or sharecropper, if

not to escape poverty itself. Each played wherever they could find an audience

willing to throw them a few coins, and as their reputations spread, more

opportunities came their way. Both Patton and Rodgers were known for their

womanizing and heavy drinking, subjects they never hid from the lyrics of the

songs they sang — songs which, though of different styles, were often similar

in their view of the world.

Though their lives were similar in

some respects, one profound social difference shaped their fates: Patton was

black, Rodgers white. Wynne does not shy away from the racial politics of

Mississippi during his subjects’ lives, but his subject is not difference

(which in many ways is obvious and taken for granted) so much as similarity. He

tries hard, and sometimes successfully, to show the ways that the gulf between

white and black lives was bridged through music.

The idea

that Patton’s and Rodgers’ careers had parallel moments is strongest before

their music is recorded. The nature of their popularity was significantly

different, and no small bit of that difference must be the result of race —

both the race of the musicians and the racialized marketing of record companies

that offered one set of music to black (and mostly Southern) audiences and

another to white (and nation-wide) audiences. Rodgers became, until

tuberculosis kept him from performing and recording regularly, a national

success, while Patton’s success was far more limited, far more regional, and restricted

by prejudices. Rodgers is not popular today, but that lack of popularity is

mostly because the quality of recordings offends the hi-fi ears of most modern

listeners and his yodelling style has gone out of fashion. But Rodgers was a

big success in a way that Charley Patton could hardly have even dreamed of for

himself. This is clear from Wynne’s account, but, like much else in the book,

it needed more analysis and context.

The

fundamental weakness of In Tune is

that Wynne tries to fit a bookshelf’s-worth of material into 200 pages. He does

an admirable job of finding useful quotations from other sources, and there is

much in In Tune that is of interest,

but it is repetitive and lacks a clear structure to its chapters. The first

chapter, “The Setting”, provides a sometimes turgid 45-page account of the

South, Mississippi, and the Delta area from the Civil War to the early 20th

century. We don’t meet the subjects of the book until the second chapter, which

spends much time on Patton and Rodgers’ ancestry, adds more detail to the

history of the areas where they were born and raised, and then, in the second

half, finally begins to explore Patton and Rodgers as musicians. The third

chapter, in many ways the book’s weakest, is a scattered look at the men’s recording

careers, with some material about Rodgers and Patton as performers that feels

repetitive after the previous chapter. The final chapter looks at the influence

of the two musicians and the fate of their posthumous reputations, a worthy

topic, but again the material in the chapter is repetitive and poorly

organized.

The value

that In Tune offers readers is its specific

comparison between two important figures in the history of American music.

There have been plenty of better books about the Delta blues and about early

country music, but there have not been nearly enough books that seek to compare

the history of the two forms (and others of the era). Wynne demonstrates that

such a comparison is valuable, and that a study of the various types of regional

and popular music of the 1920s and 1930s, their intersections and divergences,

can be fruitful. But while the comparison of Rodgers and Patton is on the

surface interesting, the result is not especially compelling, and there are few

insights in Wynne’s book that could not be gleaned from elsewhere. Wynne

provides pages and pages of historical context for Mississippi and the South,

but his portrait of the performing and recording context, while plenty wordy,

is too incomplete to be insightful. His discussion of the music itself is

disappointingly thin, with what he does provide being banal in comparison to

what is available elsewhere.

It’s an odd book, this: too

specific for a general reader who lacks knowledge of the era, location, or

music (and who would be far better served by, for instance, Ted Gioia’s Delta Blues); too general for the reader

who comes to the book with some knowledge already. The attempt, though, is

valuable, even if the result fizzles.