Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan by J. Hoberman

After Jimmy Carter's timid efforts to make America adjust to late-twentieth-century realities, Reagan installed fantasy as the motor of national consciousness, and it's still pumping disastrously along.

—Alexander Cockburn

I wouldn't wish the eighties on anyone, it was the time when all that was rotten bubbled to the surface.

—Derek Jarman

In March of 1985, President Ronald Reagan gave a speech to a business association and quoted Clint Eastwood’s most popular line from the 1983 “Dirty Harry” movie Sudden Impact: "I have only one thing to say to the tax increasers: Go ahead, make my day."

As a former Hollywood actor and head of the Screen Actors Guild, the 40th president relied on movies to help him communicate his ideas and emotions, and to help him understand the world and his place in it. Biographer Lou Cannon wrote that "Even when he was gone from Hollywood, Hollywood was never gone from him. He watched movies whenever he could, and the movies were the raw material from which he drew scenes and sustenance. He converted movie material into his own needs." He frequently quoted lines from movies in his speeches, he hosted movie stars at the White House, he watched hundreds of movies during his time as President, he named a proposed defense system after a blockbuster movie, and the CIA even presented educational documentary films during briefings to help him understand the issues of the day.

But during the Reagan years, movies weren't just a touchstone for the President alone, they were a kind of shared mass dream, or perhaps delusion. In the 1980s, movies didn't merely respond to the zeitgeist; they were a primary disseminator and shaper of the zeitgeist. Two months after Reagan was inaugurated in 1981, John Hinckley, inspired by the movie Taxi Driver and obsessed with actress Jodie Foster, shot Reagan on the afternoon of the day of the Academy Awards. Reagan had been scheduled to deliver a videotaped address at the awards ceremony; the event was postponed for one night, and included Reagan’s address. In Ronald Reagan: The Movie, Michael Rogin wrote: "Millions of Americans experienced the assassination attempt by watching it over and over again on television. The power of the film image confirmed the shooting; it also allowed Reagan to speak to the academy the next night as if the shooting had never happened."

While Reagan’s policies and worldview were inflected and influenced by the products of Hollywood, Hollywood saw significant shifts in its strategies and structures during the Reagan years. The massive commercial success of 1975’s Jaws and 1977’s Star Wars changed how Hollywood did business. The Reagan administration’s cuts in corporate tax rates, lax enforcement of anti-trust laws, and deregulation of much of the entertainment industry led to the consolidation of media companies and what Chris Jordan, in Movies and the Reagan Presidency, has called "Hollywood’s virtual return to a studio system during the 1980s."

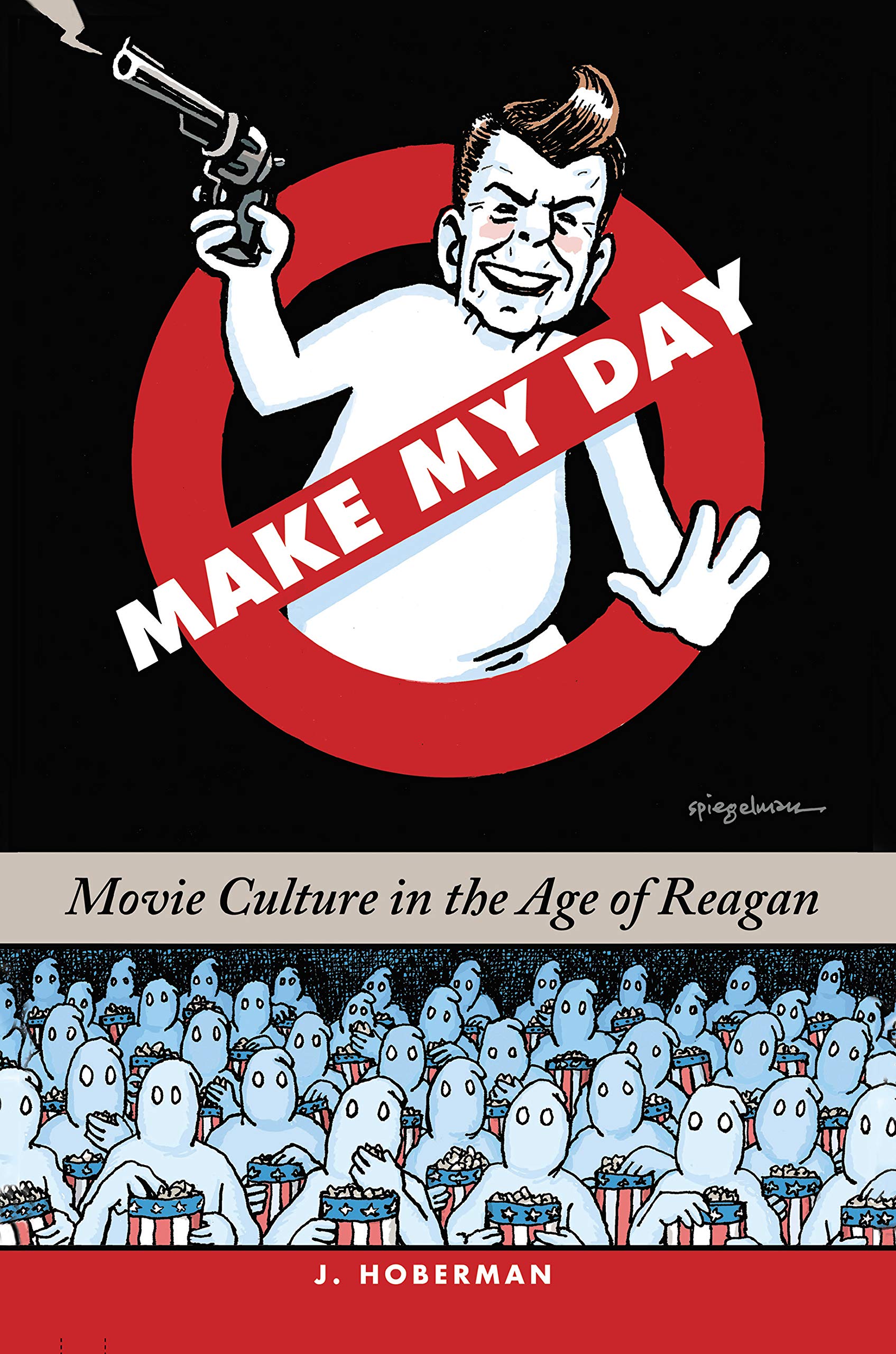

Which brings us to film critic J. Hoberman's valuable new book Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan, a tour of late-1970s and 1980s movies alongside the major events of the Reagan years. Hoberman draws from his own experience as a film reviewer for the Village Voice in the 1980s and some original scholarship — for instance, he spent time at the Reagan Library archives and found the records for what movies the Reagans watched and when, a useful body of information that gets sprinkled through the text as one of a number of running themes.

Make My Day is both a narrative and a collage, dutifully chronicling the years 1975-1988 in a linear history, but relying on careful repetitions and juxtapositions to create a montage effect rather than, as so much dreary academic writing does, signposting every thesis with, "Now I will argue..." and "Here I am proposing..." and "As I have previously bored you with..." Hoberman's pages do not lack for information and insight, but instead of constantly restating itself, Make My Day allows readers to build a panoramic image of the argument in their minds from the relationship between the various individual pieces.

"If," Hoberman writes, "the Sixties and early Seventies were, at least in part, periods of disillusionment, the late Seventies and Eighties brought a process of re-illusionment. Its agent was Ronald Reagan. His mandate wasn't simply to restore America's economy and sense of military superiority but also, even more crucially, its innocence." This is the panoramic view we can put together as we read, a view of how Reagan enlisted the dream factory in his ideological army, reshaping the dreams themselves while also, and more importantly, reshaping how those dreams were dreamt and interpreted.

Like many writers on Reagan, Hoberman starts before the 1981 inauguration. It's possible to see the whole of the 1970s as a prelude to Reagan, or to go back even further to Reagan's time as governor of California, or even further than that, to his time at General Electric, or his support of McCarthyism, or... (I've sometimes thought 1971 is an interesting starting point for looking at Reagan and popular culture: the year of Billy Jack, Straw Dogs, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, The French Connection, Clockwork Orange, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, etc. — and the year when John Wayne starred in Big Jake and Clint Eastwood starred in three movies: The Beguiled, Dirty Harry, and Play Misty for Me, the latter of which was the first film he directed. It was the year Eastwood definitively inherited Wayne's mantle, updating Wayne's violent machismo for the new age.) Hoberman starts with 1975, contrasting two "antithetical yet analogous" movies released in June of that year, Jaws and Nashville. "Each," Hoberman says, "in its way brilliantly modified the cycle of 'disaster' films that had appeared during Richard Nixon's second term and were now, at the nadir of the nation's self-esteem, paralleled by the spectacular collapse of South Vietnam and the unprecedented Watergate drama."

Throughout, Hoberman offers provocative views of the films he discusses — for instance, "Structurally, Rocky resembles the second half of The Birth of a Nation, with blacks having displaced whites and whites — or at least the white protagonist — redeemed when Rocky goes the distance." Or: "E.T. brought together the two master tropes of 1980s Hollywood — the narcissistic fantasy of the stranger in (our) paradise and the joyful recuperation of the authoritarian Fifties — presenting them in such a way as to restore universal faith in smoke and mirrors."

But the book is not a collection of movie reviews, and it is at least as much cultural history as it is film criticism. As such, much will escape its grasp: this is a panoramic, not microscopic, study. This seems to me to be a good choice, because there are lots of less panoramic studies of Reagan and popular culture, including some that Hoberman draws from (particularly Susan Jeffords' vital Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era, though it seems odd that Hoberman makes no reference to Jeffords' earlier book, The Remasculinization of America: Gender and the Vietnam War, since it fits well with his idea of re-illusionment. But there's only room for so much, and Hoberman wisely doesn't bog the narrative down with copious references to scholarship). It makes a nice companion to Gil Troy's more wide-ranging, Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s. Troy highlights why cultural histories of Reaganism are so important: "Armed with his easy grin, his sunny disposition, and an array of anecdotes trumpeting traditional American values, Reagan repeatedly merged culture and politics. ... Reagan demonstrated that politics was more than a power game and a question of resource allocation, it often involved a clash of symbols and a collective search for meaning."

One of the repeated elements of Make My Day is Hoberman's use of contemporary reviews of the films he discusses. He juxtaposes his hindsighted perspective with the ways popular films were received by major media at the time when those films were new. He complicates this by reprinting some of his own Village Voice articles in the text, separated by a line in the margin and a change to san serif typeface, adding commentary and updates via footnotes. Footnotes, in fact, fill the whole text, encouraging a further back-and-forth movement from the reader, not just past-to-present and back, but from main text to note. The effect is palimpsestic: information gets expanded, voices from past and present circulate, tangential remarks offer powerful new ideas, and we as readers have to choose how we will assimilate all this material in our minds, what we will (literally) make of it. Since his opinions of Reagan and the films haven't much changed since the 1980s, some of Hoberman's old Voice pieces might have benefited from being more excerpted than reprinted so fully (particularly the last one, which by that point in the book is simply tedious), the articles have an energy of their own, their rage and incredulity being fresh. And there are some gems of insight, for instance this from a piece titled "Stars & Hype Forever", published in January 1985, after Reagan's second inauguration: "In its most virulent form, the mass Reaganism of 1984 — a true pop phenomenon like Beatlemania — was a combination of yearning and denial, puritanism and greed, all tied up in one jumbo family-sized package of all-natural space-age old-fascioned new-and-improved jingoistic hoopla." The gaps between Reagan's life and image were clear:

Is Ronald Reagan the greatest American who ever lived, or is he only the most American? Only a few recalcitrant minorities seemed able to resist the spectacle of the seventy-three-year-old ex-actor waxing nostalgic for God, neighborliness, the nuclear family, strong leadership, the work ethic, and the small-town community. Especially since — as everyone knew — he himself seldom attended church, rarely gave to charity, was divorced by his first wife, communicated badly with his children (and indeed everyone else if there was no script), failed to control his own staff, kept bankers' hours, hung out with a passel of corrupt billionaires, and had fled his small town (scarcely a Norman Rockwell paradise but a place where his father had been the local drunk) for the fleshpots of California at his earliest opportunity.The realities of Reagan's life didn't matter any more than the realities of his policies. Reagan, much like the blockbuster films of the '80s, was a triumph of image and sentiment. There had long been an element of celebrity to American politics, and that element only grew more and more important as audiovisual media made politicians indistinguishable from movie stars. Reagan was the apotheosis of this trend, the ultimate illustration of its triumph: If, to get elected, the president must now be like a movie star, why not have an actual movie star for president?

Voters wanted to feel good, and Reagan achieved that for his supporters perhaps better than any president in history. His ascent to the presidency was no accident: he had been preparing for it for a long time, conservative activists of the Goldwater side of the Republican party had been seeding the soil for decades (see Rick Perlstein's Before the Storm), and, most importantly, Carter was seen as a downer, the captain of malaise. Go back and watch some 1970s movies and you'll likely be shocked by the bleakness and sheer nihilism of more than a few of them — not just the artsy movies of the New Hollywood, but many of the mainstream films of those years, when urban decay, vigilante justice, and cataclysmic disasters showed up every week at the Main Street cinema.

Hoberman sees the beginning of a turn in Rocky's triumph at the Oscars in March 1977:

Aggressively innocent and proudly upbeat, Stallone's underdog psychodrama demonstrated that movies were about making audiences feel good about themselves (and America). The fantasy of realizing an impossible dream against all odds was resurrected as a Hollywood staple, even as the Rocky theme would become the default musical introduction for American politicians. ... If Taxi Driver was Hollywood's last great feel-bad movie, Rocky — which mainly redeemed Hollywood, but also boxing, showbiz, America, and post-Vietnam masculinity — created the template for the feel-good movies that would endure for the rest of the twentieth century and beyond. The Bicentennial Year saw a dip in box-office figures, but the setback was only momentary: grosses took off over the next few years as a new zeitgeist came to roost. Powered by the astounding, unforseen success of Star Wars in 1977, the period between November 1976 and November 1978 proved to be a watershed for the themes and trends of the next half-dozen years.Stallone of course would prove to be one of the most successful stars of those years, not just with the Rocky sequels, but also with his other franchise, the Rambo movies. (I've written about those films myself.) In a recent interview with Rolling Stone, Hoberman said he was tempted to pick Rambo: First Blood, Part II as the film that sums up the Reagan years, but he doesn't choose it because "it seems too oppressive that Rambo would be the quintessential statement from that era." (He names some alternatives — Blade Runner, Ishtar, The Terminator, The King of Comedy — before settling on Blue Velvet.) Rambo came out in the summer of 1985, and then Rocky IV was released that November. That's the one with Dolph Lundgren as the Russian Drago. A lawyer and writer named Timothy Anderson had written a script that offered this idea of Rocky vs. a Rusky. He brought it to White House Deputy Chief of Staff Michael Deaver, who then set up a meeting with Stallone. Hoberman quotes a letter from Anderson to Deaver: "I assume you realize the possible positive impact that my version of Rocky IV could have upon the national electorate should it be released in mid-summer, 1984." It would have been quite the campaign movie, but Reagan didn't end up needing Rocky's help getting re-elected, managing to KO Walter Mondale just fine on his own. Rocky IV instead became a kind of celebration of Reagan's triumph a year after the election, a manifesto of Reaganism in pop culture. (Anderson later sued Stallone for copyright infringement, but lost, since he had been the first infringer, using Stallone's copyrighted characters. Threatening appeal, Anderson convinced Stallone to settle out of court.)

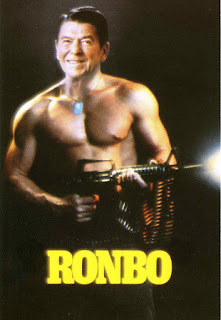

Reagan, to his own joy, ultimately became more associated with the figure of Rambo than Rocky. Boxing is nice, but vigilante imperialism with massive phallic weaponry is more fun.

Hoberman doesn't have space to get into the details of the paramilitary fantasies of the Reagan era, though he covers most of the militaristic greatest hits of the time: the Grenada invasion, the MIA issue, recuperation of the Vietnam War, the "Star Wars" Strategic Defense Initiative, etc. He's good on the general militarism of films like Firefox, Top Gun, Red Dawn, Iron Eagle, and others, as well as the Pentagon's powerful effect in Hollywood.

The paramilitarism was at least as pervasive as the militarism, and its legacy continues to this day. It's worth supplementing Make My Day with books covering some material beyond its scope such as Warrior Dreams: Violence and Manhood in Post-Vietnam America by James William Gibson, Revolutionaries for the Right: Anticommunist Internationalism and Paramilitary Warfare in the Cold War by Kyle Burke, and Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America by Kathleen Belew, books that show how the aw-shucks jingoism of the Reagan imaginary directly led not only to the Iran-Contra imbroglio, but to Ruby Ridge, Oklahoma City, the Bundy standoff, Charleston, Charlottesville, etc. In terms of paramilitarism, at least, we're still living in the Age of Reagan.

Even after the disasters of our unending war in the Middle East, the militaristic assumptions of the Reagan era remain strong across partisan lines (Clinton, too, liked bombing; Obama became King of the Drones; few presidential candidates from either of the major parties have offered much difference in foreign policy since Reagan). As George Carlin said shortly after Bush the First invaded Kuwait, "We like war! We're a war-like people!" This is as clear in our popular culture as it is in our politics.

Now, though, we live in the Age of Trump. Hoberman began writing his book before Trump was elected, and finished it last year. He accounts for Trump in an epilogue. "Reagan was an actor who built a career as a professional image. So too Trump. As an actor, Reagan intuitively grasped how a president (or a good Joe or action hero) is supposed to present himself. As a celebrity, Trump understood what it took to land on the front page of the New York Post. The only person with neither political nor military experience ever elected president, Trump was famous less for his actual real estate transactions than for a ghostwritten best-seller about real estate transactions, The Art of the Deal. As president, JFK became a brand; Trump already was one." Reagan was well known for being uninterested in policy details and impervious to facts — he once famously slipped and said, "Facts are stupid things." He even explained his part in the Iran-Contra dealings on national television thus: "A few months ago I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages. My heart and my best intentions tell me that's true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not." But compared to Trump, that doublespeak is a height of honesty and clear thinking, because Trump would just deny that there were any contradictory facts. Trump doesn't simply live in his own little world where he is always right and wonderful; he insists the rest of us must live there, too.

One of the biggest differences between Reagan and Trump is the type of emotions they encourage. In Campaigning for Hearts and Minds: How Emotional Appeals in Political Ads Work, Ted Brader proposes that political advertising appeals to one of two primary emotions: enthusiasm or fear. (He notes that of course ads appeal to other, often related, emotions as well: enthusiasm is closely linked with hope and pride, fear is linked with anger, etc., But enthusiasm and fear are easily differentiated, pervasive, and able to be identified and studied for research purposes.) While Reagan certainly made appeals to fear (especially of what Hoberman identifies as the Alien Other), I don't think it's controversial to say that the dominant emotion Reagan became known for was enthusiasm: enthusiasm for a particular idea of the United States, especially — a hopeful idea, an idea of American pride based, as Hoberman is only the most recent to show, on an idea of a mythical 1950s structured by a procreative, heteronormalized, patriarchal nuclear family; a pride in US military force and American exceptionalism; a naive idea of capitalism; the superiority of whiteness...

Trump's only enthusiasm is for himself. Fear, though, he sells like the brilliant demagogue he is. This is a significant political shift at the level of the president, at least in its success, because as Brader points out, enthusiasm is the emotion candidates usually like to promote themselves, if they can, leaving fear to be promoted by their underlings and outside agents. But Trump has weaponized fear and anger for his purposes much as Reagan weaponized enthusiasm and hope for his. And then there is the sadism. Though the effect of Reagan's policies was often cruel, even murderous, I've never read anything from even his most fervent detractors to suggest that his motivation and goal was cruelty. But Adam Serwer was onto something when he said of Trump and his supporters that the cruelty is the point. That cruelty has long been part of American politics and American ideology, but with Trump it is particularly naked.

What this means for popular culture now is difficult to say, especially when the media landscape is so significantly more fractured than it was in Reagan's day, when a network like Fox News and a tool like Twitter were less imaginable than space lasers. Whether Trump's sadism has reshaped popular film and media in anything like the way Reagan's what-me-worry machismo and imperialism did, it's too early to say. Hollywood is full of sadists and conservatives, but they tend to prefer certain political aesthetics over others, and Trump is gauche. The Trump influence on popular culture may not require that Hollywood embrace him as it did Reagan, however. Trump isn't actually good at much, but he's a genius at manipulating the media machinery. For all the talk of vigilance against the "erosion of norms", the major media have been unable to deal with the pure product of American id that is Trump. That will have an effect beyond the news media; it will seep into the cinematic, if it hasn't already.

In any case, Hoberman provides a good guide to how Reagan and Hollywood mutually influenced and supported each other, and so encourages us to think about the ways we allow politics to be entertainment, and entertainment to shape our politics. Or if the two are even separable anymore.